A good warm up

DIDIER HEUMANN, MILENA DALLA PIAZZA, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

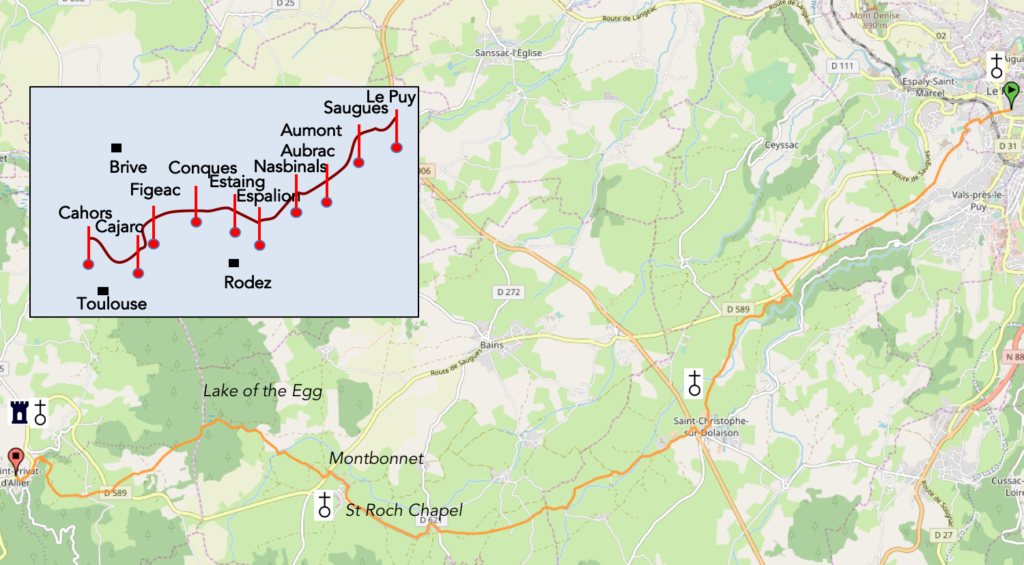

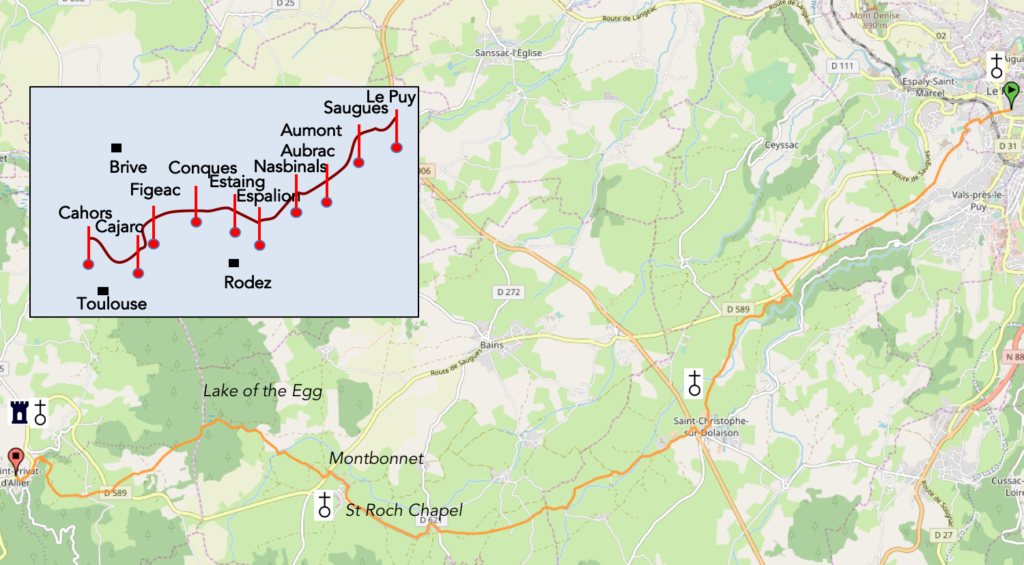

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the roads. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/du-puy-en-velay-a-st-privat-dallier-par-le-gr65-29068056

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in France without an Internet connection. Therefore, you can find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the book title to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Many pilgrims and hikers start the way to Santiago in Puy-en-Velay. The first stage is not a walk of health. We might wonder why novice walkers should have to face such a difficult task from the start, with a bag that is often too heavy or shoes that may not be suitable for walking? For the athlete, it’s an ordinary stage. Yet, are there really ordinary steps? The track changes every day, and every day is a new day.

The Velay region was born from the erosion of complex volcanoes that arose in a granite basement. It’s a long story. The volcanoes exploded on a primitive granite base 1000 meters high, spilling lava on lava up to 2500 meters at least height. Later, when Vulcain and Hephaestus, it is according to, decided to stop their convulsionary vomiting, erosion settled. Every millennium left the landscape lower, less compact, with fragmented puys, abysses and precipices, gnawed by rivers. On this base of slag and volcanic ash, rivers and glaciers have slowly carried soft sediments, such as marl and lake limestone, smoothed the landscape to create vast plateaus. But basalt is resistant like iron. Nature has little reason for its power. The small rounded hills of Le Puy have resisted the progressive erosion and the three famous rocks of Le Puy, the rock Corneille, the rock Saint-Michel and the Mount Anis are still the visible needles of these antique volcanic chimneys.

Agriculture, particularly livestock, is omnipresent. Fields and meadows of modest size succeed one another. This agricultural landscape leaves little space for the forest, although many small groves crisscross the area. The plateau was formed by the piling up of successive large basaltic volcanic flows. Small volcanic hills sometimes rise above the plateau. They are called here “guards”, covered with fertile ground with, at the top, pines or moors. Due to the presence of many volcanic craters, peat bogs have been created in Devès. The Lake de l’Oeuf, where the GR65 runs, is a striking example. Devès is dominated by agriculture and livestock. Crops are rarer. Farms are often marked by hedgerows of hazel and ash trees. The peasants have removed the troublesome blocks of stone to favor plowing, making small walls, which decorate the grove.

The villages are relatively compact, articulated around a church or a castle, organized around a place or a “couderc”, a public space, translates, as on the territory of the neighboring Margeride, a community tradition marked by the presence of a bread oven, wash houses, fountains, crafts to shoe the oxen. For the houses, the men chose the volcanic stone, the material available on the spot. The dark, dull stones give the villages an austere touch.

The route heads southwest out of Le Puy, from the Loire River Basin to the Allier River. You are on Le Devès Mountain plateau, in Velay region, where the edges are deeply cut by the River Loire in the east and by the Allier in the west. A few valleys carve horizontal lines in the landscape.

Difficulty of the course: The stage is entirely in Haute-Loire. You are already in the typical landscapes of the Massif Central, made of small wooded mountains, but sometimes also with deep gorges. Nature is deeply tortured here. In this stage, slope variations are relatively substantial, but the slope is gradual and quite bearable (+649 meters /-389 meters). It will be a gradual climb towards the Monts du Devès. From up there, you can see Margeride region in the distance, and further still, Aubrac area. For a start on the Camino de Santiago, it’s a good start, isn’t it? 23.2 km of walking and more than 600 meters of positive slope to reach the Monts of Devès. A descent, not always light, sometimes very tough on the stones, leads the pilgrim to St Privat d’Allier.

Throughout this stage, you walk more on dirt roads than on paved roads, which is not always the case on the Road to Santiago:

- Paved roads: 9.5 km

- Dirt roads:13.7 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on Via Podiensis. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

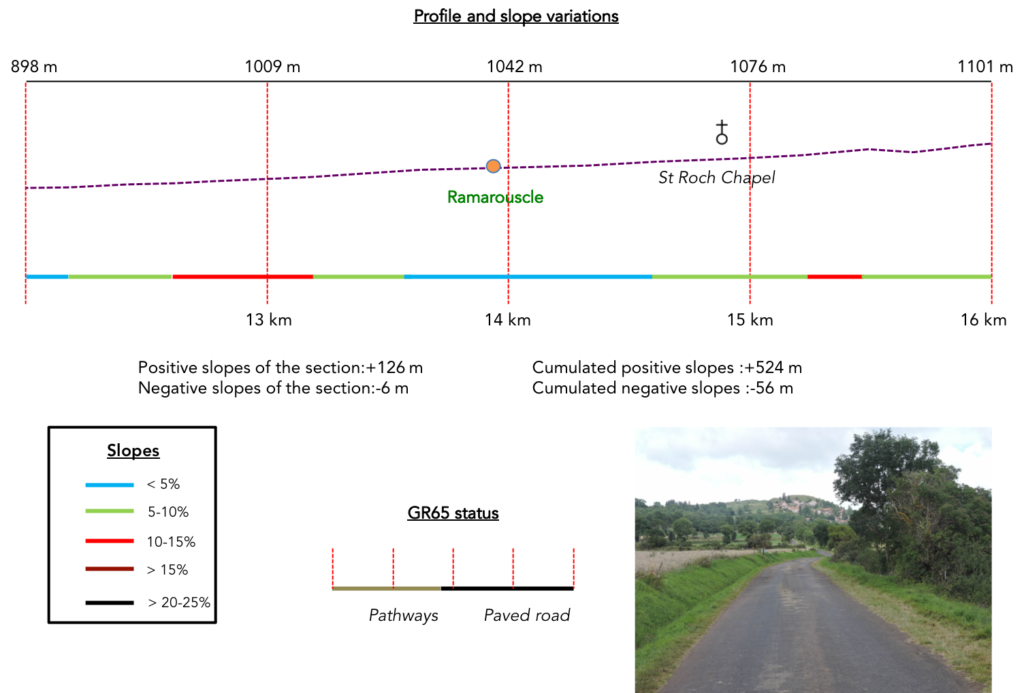

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

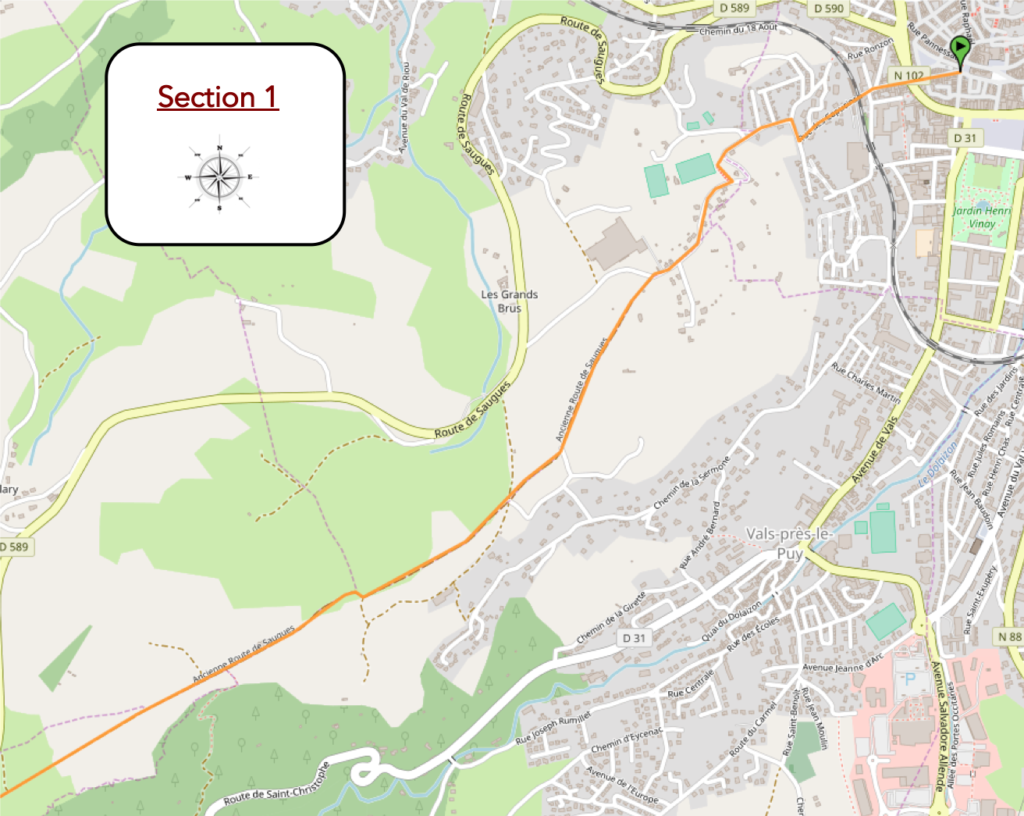

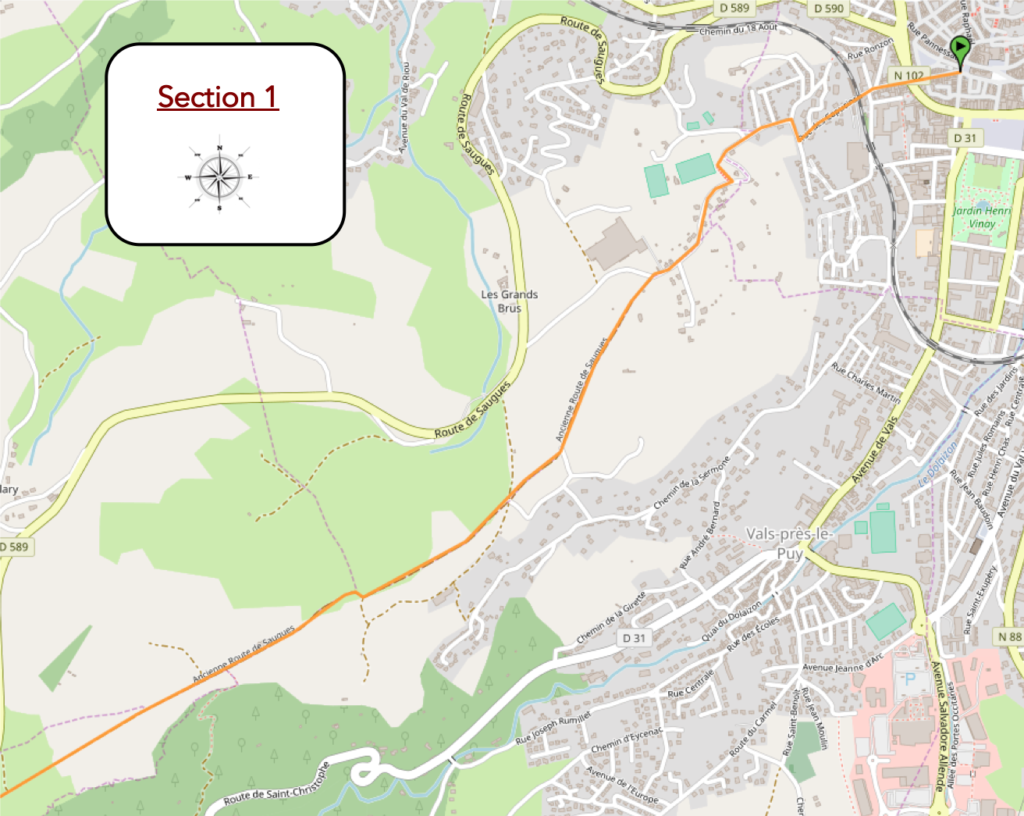

Section 1: A slightly steep start to walk up to the plateau.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: after a relatively difficult start, the route calms down quite quickly.

|

In the Middle Ages, it was from the parvis of Notre Dame that pilgrims rushed to distant Galicia, at the first of the 102 steps that connect the low streets to the upper town. It is still today, in the early hours of the morning, at exactly seven o’clock, when most pilgrims attend mass and blessing. At these times, the city is empty.

Today, there are a hundred or so pilgrims present at Mass, in front of the Black Madonna. It is a traditional Mass, with many recommendations and advice, delivered in many languages, on the pilgrimage. They also deliver the “credencial”, the stamping passport of the Santiago Track, for pilgrims who do not have one yet. |

|

|

| For the occasion, the grand staircase of the church is opened, closed for the visits, and the pilgrims leave one by one the church. They slope down the Rue des Tables towards the intersection of St Jacques Street and Grand Boulevard St Louis. |

|

|

| Just near is the Rue des Capucins, the real starting point of Via Podiensis. The gîte des Capucins (Capuchins) is the heart of the pilgrimage set-up in Le Puy. Many pilgrims leave here, having spent the night either at the hotel or in the gîte itself. Each according to his purse! |

|

|

| In the Rue des Capucins, the uninformed pilgrim will quickly realize that the Camino de Santiago is no piece of cake. For a starter, it’s rather tough. GR path runs up on a narrow sidewalk. |

|

|

| Everywhere, the signs remind the pilgrim that he did not go for a Sunday walk. 1521 kilometers, this marks the spirits, and the calves too! |

|

|

| Further ahead, the GR65 gets to the Rue de Compostelle, but the road remains steep nonetheless. The Rue de Compostelle twists and gets lost in the heights of the suburbs. The road then leaves the city for the suburbs of Espaly St Marcel. And the slope is getting tougher. |

|

|

On the road pilgrims roam like so many rosary beads. As on all long walking trails, walkers are very numerous at the beginning, but the number sharply declines over the miles. There are pilgrims who leave quickly, forcing their talent. They make a point of being first at the top of the hill. There are anxious pilgrims, the dreamers, trying to delay the moment when they are really gone. Others discover the first slopes of the track. So, they pause, taking pictures of the highs of the city. Then, they start again, taking the step. Youth is not the preserve of pilgrims. Retired people for the most part, who walk alone, in couples or in more consistent groups. Some wear the symbolic shell around the neck or hung on the bag. The shell is not just a symbol. It is a bridge with the invisible, a protective companion to go to the end of the journey. You’ll also encounter pilgrims accompanied by a dog, sometimes connected to them by a harness. Rarer are the donkeys or the horses.

Looking back, you can still catch a glimpse to the cathedral and Notre-Dame-de-France perched on Corneille rock. From here, you will not see St Michel d’Aiguilhe Chapel.

| The slope is steep, sometimes more than 15% in the first kilometer. After a passage on small stairs, the road slopes up in the middle of recent houses. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope calms down when the road heads to a place known as Sejalat, near a large factory where lace is made. |

|

|

| The GR65 then abandons the paved road for a wide gravel road, which flattens in the countryside. This is the former road to Saugues, a dirt road. Here there are still marked traces of recent rains. And today, the weather is not encouraging, either. |

|

|

| The dirt road runs near ancient “sucs”, cones also called in the country “guards”, in other words small volcanoes remodeled by erosion, with sharply blunt forms, made of red stones, exploited under the pretty name of pozzolana. Puy-en-Velay flies away, in the middle of the roundness of the small volcanoes which are the charm of the Velay. |

|

|

Along the way, you’ll come across the Polignac Cross. Destroyed in 1940 by lightning, the base dating from the 12th century, it was no more than a tossed column. It has been recently restored. The scepters dominate the world, but the crosses are the keys of Heaven. No one can tell from what time the thousands of crosses that you meet on the Camino de Santiago date back to, a custom that goes back a long way in the early days of evangelization. Initiatives of the parishes, act of individual piety, commemoration of an event, they served and still serve to mark the way, the village, the parish, to provide a stop for the processions that are becoming increasingly rare.

| The pathway then runs on long false flats, across fields. It is tainted with brown and red dust, reflecting somewhat the volcanic origin of the region. Here the sky is so low that it seems to plunge into the ground, meadows and rare crops. It is undulating land, agriculture, with few crops and sometimes livestock. If you come here on a windy day, you will find that the plateau can be siphoned by the wind. Rare hardwoods, including hornbeams, ash trees and maples sometimes camp near the walls of loose stones, rose hips and brambles. |

|

|

| In the valley of Dolaison, below the road, many “chibottes” are present. A track is devolved. Few “chibottes” are present here on the GR65.

When people were given land to cultivate, they often gave up the ornaments, focusing first on the useful. Modest huts for shepherds and laborers were born. The future fields had to be cleared of stones. People had understood how to join the useful with the convenience, not the pleasant. The “chibottes” or “tsabones”, dry stone huts, are still visible in Haute-Loire, particularly in the valley of the Dolaison. Volcanic stones were collected in plowing to build these huts, like igloos. They were, then, temporary, seasonal dwellings for the work of the fields and the vines, which were occupied during the summer. Some even had heating. These miserable hovels were abandoned in the years 1920-1930. They are nowadays only tourist attractions. |

|

|

| A little farther on, the pathway becomes less gravelly, turns on the ocher, steeply slopes up to an isolated farmhouse at Conflans, just below the “guard” of Croustet. |

|

|

| Then it smoothens again, almost rectilinear, along the hedgerows of small hardwoods and weeds. |

|

|

In this uniform landscape, you’ll cross meadows in abundance. By the time we describe the stage, the cattle are rare, but you can walk here to other seasons and see many cows or sheep frolicking in the meadows. Crops are quite rare here, with a little bit of corn and little wheat.

Section 2: Along the high plateau.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: sometimes some slopes, but they are brief. Easy way.

| Shortly after, after a long straight, the route passes on the other side of the D589, the departmental road that runs through the region. |

|

|

|

You get at a place known as Les Fangeasses. It is always so. Every time you start a new Santiago track, the signs flourish, well organized and clear. This is often spoiled later. Too bad, but anyway you rarely get lost. |

|

| The dirt road, which has become narrower but often still so red, strolls through meadows among brambles and weeds, sometimes with hornbeam bushes and solitary ash trees. The floor is sometimes a carpet of pozzolana, these small alveolar stones, which are volcanic slags. They can be red or black. Here they are red. |

|

|

| At a place known as La Sagne, near a little civilization, the pathway turns at right angles. Here pilgrims are warned not to be turned away by bad counselors. Is this really common? For our part, after thousands of miles on the Santiago track, we have never been worried about it. |

|

|

| Shortly before La Roche, at the exit of the hamlet of La Sagne, the route cuts again the D589 departmental road, which runs from Le Puy to St Privat d’Allier. |

|

|

| A small paved road then runs along an incredible collection of farms, all identical, made of large blocks of black basalt, whitewashed under their red tile roofs. |

|

|

| Further ahead, a steep pathway slopes up and down below the village. La Roche is a small hamlet straddling a cornice overlooking a deep valley where flows, at the bottom, Dolaison River. In the village, great is the order of the place, whichever way one turns. To say that it is the stone that dominates here is to say little. It’s a string of houses, all in the same uniform, as if they were born on the same day. Same pattern, same color. Basalt is not a stone that was missing here. But all the quarrymen will say that the basalt is a brittle stone, difficult to carve in the square. Never mind! The ancients used it in the form of large irregular blocks or sometimes hastily cut, joined with lime or mortar. The other volcanic stones, they were also slipped in the walls or sometimes in plates on the roofs, to make “lauzes” (stone slates). |

|

|

| Here stands an iron tool that looks like an instrument of torture. Yet, it was not for the use of humans, but oxen. Poor oxen, all the same! It is an old craft to shoe oxen, also called “work”. If for a docile horse, shoeing is done without much hindrance, the blacksmith used “work” for cows and oxen who cannot stand on three legs. Of course, there is no longer any ox that pulls the cart. Happy region that has preserved its heritage!

You are at the beginning of the Via Podiensis, and sometimes a few stops show their interest in not letting the pilgrim die of hunger and thirst. Here the keeper has probably gone to take a break. |

|

|

| The GR65 leaves this incredible village, where no recent construction changes the unit, at least where the route runs. The walls are sometimes so high that you may think about a fortress. |

|

|

| At the exit of the village, a narrow lane, filled with pebbles of all sizes, follows the cornice, flattens on the upper lip of the crest, above the ravine of the Gazelle. Underneath flows Dolaison River. |

|

|

Here you can play leapfrog, but it’s even funnier when it rains, which is not the case today.

Wait for the video to load.

| In this steppe, where the granite outcrops, sometimes the cattle eat the grass. The horizon is a line of ridges profiled at 1000 meters altitude. It is the heart of the Velay, a large volcanic platform, lined in front of you by the mountains of Devès and its innumerable small volcanoes. Devès chain is the dividing line between the Loire basin, to the east, and that of the Allier, to the west. |

|

|

| At the end of the ridge, the pathway widens and slowly slopes downhill in the undergrowth. |

|

|

| It arrives at the place known as The Earth of the Church. The outcropping rocks are granites as are the crosses. Yet, the stones of the dirt road remain of volcanic origin. |

|

|

| The ground sometimes ocher, despite small pebbles who took pension, is pleasant for walking in the ferns. Then appear the first walls of dry stone covered with moss, so characteristic of GR path, under the trees. You’ll meet ash trees and maples everywhere. The oaks begin to show up, as well as some spruces and some pines. |

|

|

| The pathway then gently slopes down to cross the small Roche brook on an arched bridge. The water does not flow at a high level. |

|

|

| Beyond the stream the dirt road slopes uphill back into the undergrowth where the vegetation becomes exuberant. Even the alders compete with oaks, maples and hornbeam bushes. In rainy weather, these sloping trails, whether soft as here or more pronounced, sometimes turn into real streams. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the ash trees show up and the lichen is encrusted in the undergrowth until you reach the village of St Christophe-sur-Dolaison. |

|

|

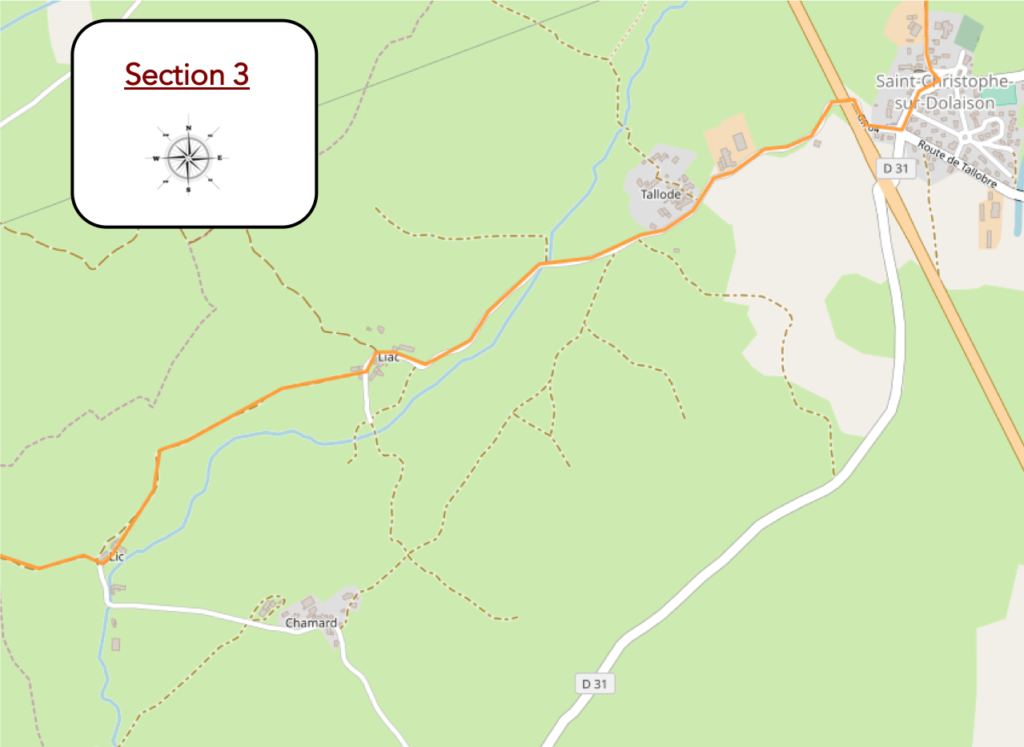

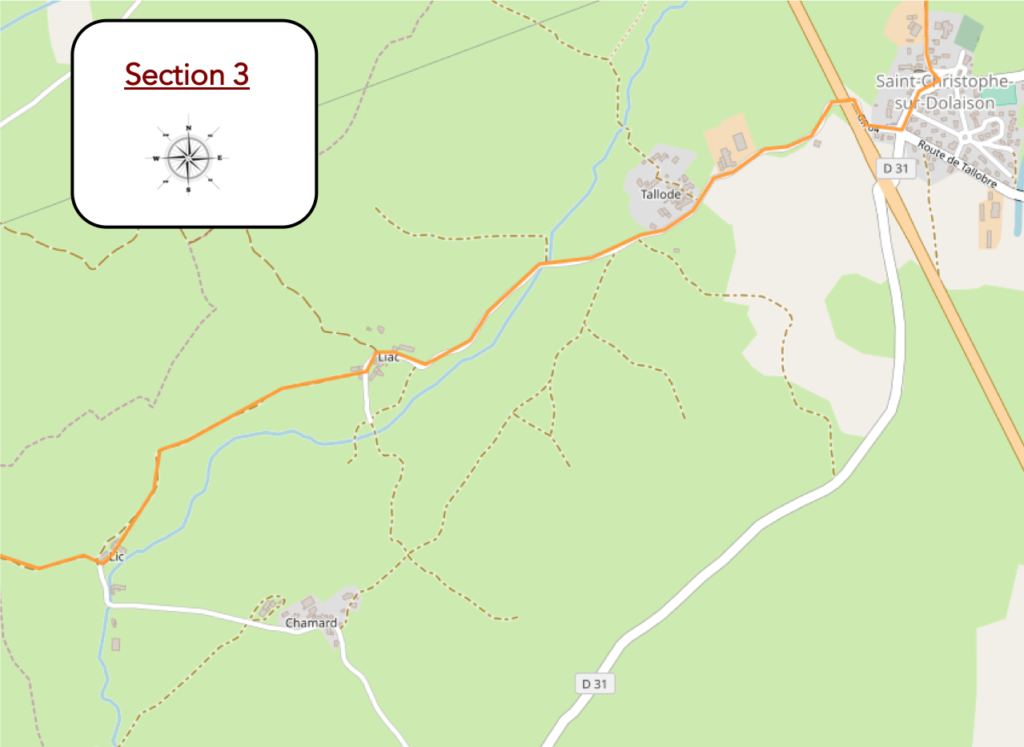

Section 3: Beyond St Christophe-sur -Dolaison, small stone hamlets in the countryside.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without difficulty.

| St Christophe-sur-Dolaison is articulated around a small place, where is the church. The church, historical monument, dates back to the XIIth century, indicated by the Hospitaliers of Le Puy and the Knights Templar who inhabited the region. Its basic material is volcanic breccia, in fact a natural conglomerate of fragments of volcanic rocks linked by volcanic ash cement. The walls have all the shades of ocher to red, and the church is covered with a very curious belfry with its four openings that make like a belfry comb. The comb tower is a trademark of the entire region. Over time, the church underwent slight modifications, including the addition of a chapel and a staircase. |

|

|

|

|

| You can have food in the village, as long as you pass along there during opening hours. It must be emphasized here that you will often be disappointed to find a closed door on the way. The solution is to take its information in the previous stage. There, they can inform you of what is open or closed. Only water points are always available, which is still the viaticum for thirsty walkers.

Here too, as in all the villages of the region, volcanic rocks burst of all colors in the houses. |

|

|

| Beyond St Christophe-sur-Dolaison, a few hundred meters further, the route passes in front of the Place du Lavoir, and slopes down to cross the D51 road. |

|

|

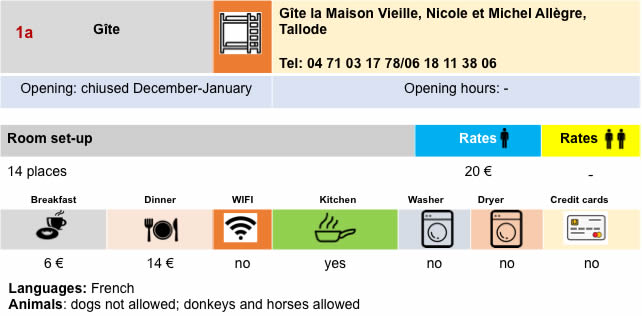

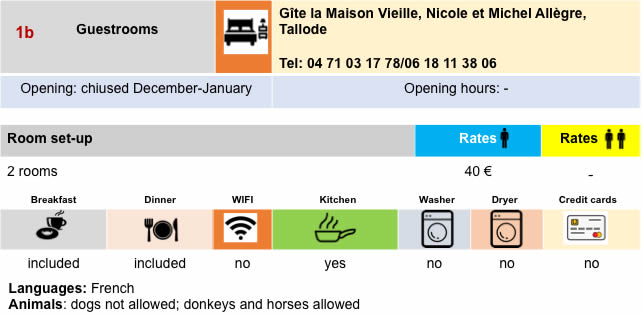

| A paved road then gently climbs towards Tallode, 10 km away from Puy-en-Velay. |

|

|

At Tallode, the houses have a remarkable unity under their basaltic stones. These hamlets that you meet on the way, they are small handfuls of massive houses, made to last beyond time. They are magnificent houses in truth, of many centuries. The men carved here in the granite and basaltic cliffs, black and gray, cut the oaks to make emerge farms, barns, sometimes mansions.

Look out! In Velay, granite was there before every other stone. It’s a 300-million-year-old gentleman, while Vulcan and Hephaestus were only toddlers and started playing marbles here just 15 million years ago. So, sometimes the granite, which is easily cut, replaces the basalt.

| The paved road then heads to Liac in the countryside. |

|

|

| On the road, at the place known as Pré Neuf, the alternative is walk to Bains, then further to the Lake de L’Oeuf. |

|

|

| Gentle climbs and descents, a pleasant mixture of fields, meadows, groves of ash trees, flocks that roam freely in the blooming grass, that’s the program. |

|

|

| The road soon gets to Liac hamlet. Here again a “work” in iron to shoe oxen. |

|

|

| And still the magic of these volcanic stones that have not been randomly aligned in massive houses, made to resist time. In these villages, even the houses have been transformed in the same state of mind. |

|

|

| Later on, the GR65 leaves Liac, still on the paved road, sometimes along stone walls, under ash trees and maples. |

|

|

| A little further, the tar gives way to an ocher clay. The dirt road flattens and smoothens until Lic hamlet, where again some paved road is present. |

|

|

| The solid granite crosses are present everywhere here, in the villages and along the way. |

|

|

| At the exit of Lic, it is full campaign on the dirt or on the grass. |

|

|

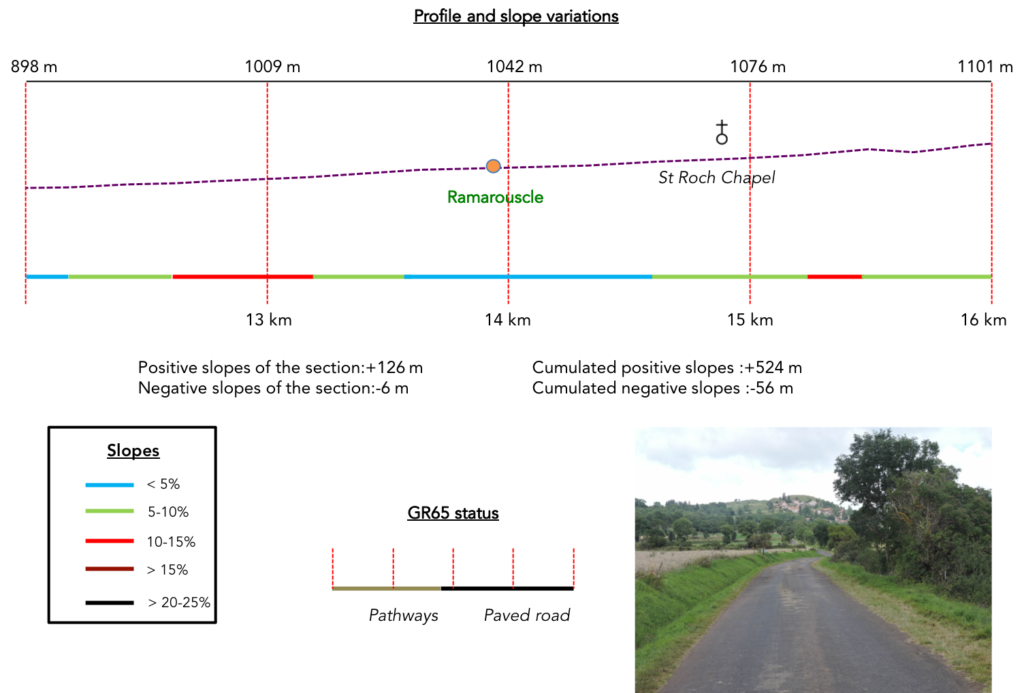

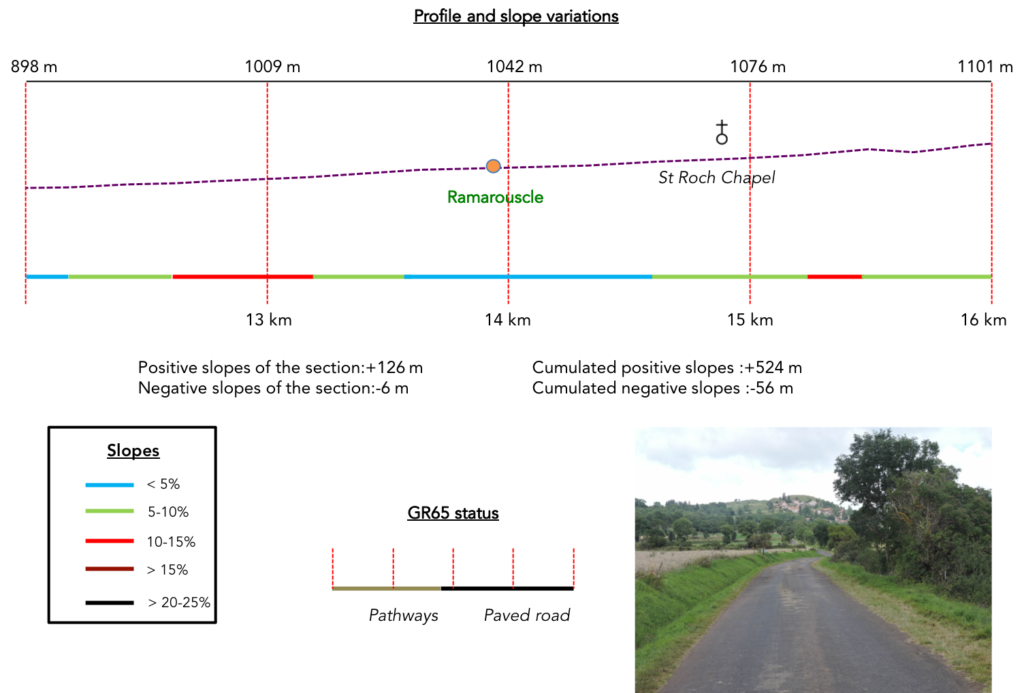

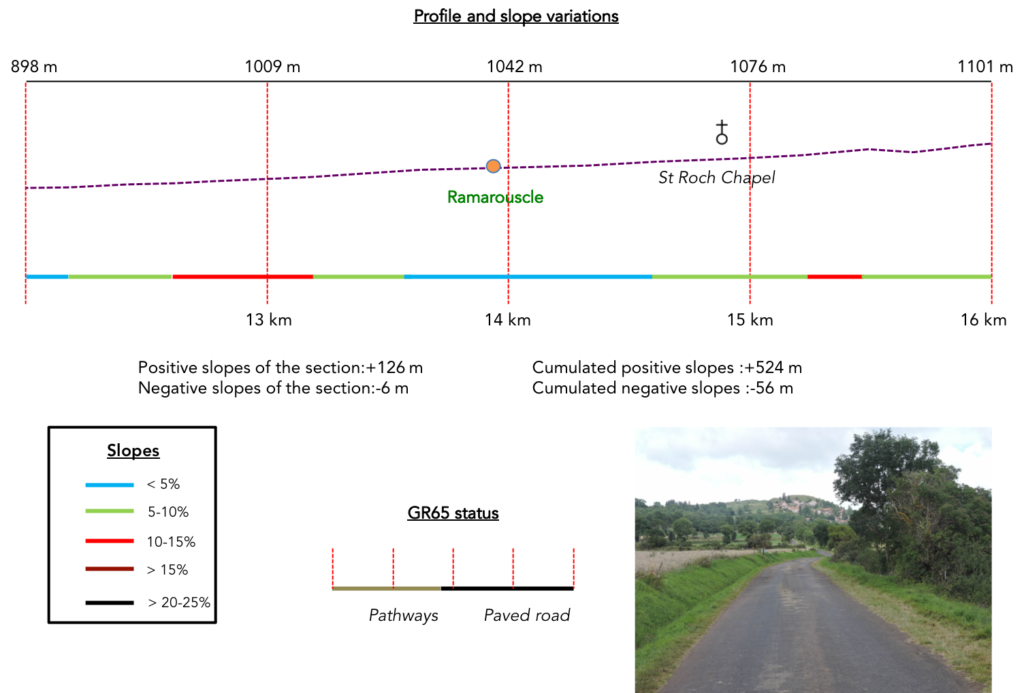

Section 4: The beautiful stones of Ramourouscle and a solitary chapel in the countryside.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: the route slopes uphill constantly, but always less than 10% of slope, most often less than 5%.

| Beyond here, the GR65 slightly climbs in the countryside. Sometimes large volcanic stones come out of a field. Here they are mostly grasslands and there are few cultivated fields. You’ll find a little corn, a little wheat. But for lenses, the flagship of Puy, you are apparently not in the production area. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the ocher pathway covered with remains of pozzolana crosses a small road, where you have the choice again to transit to Les Bains. Yet, the GR65 still continues straight along the brambles and tall grasses. |

|

|

| The route then alternatively hesitates between mud and the ocher ground. Sometimes when the spring has been rainy, it is better not to go through the fields to avoid getting bogged down. The nature of the soil here favors water retention. Signs placed here and there signal deviations in case of severe weather. Follow them according to the time. The advice will not leave you indifferent. |

|

|

| And for good reason. A narrow lane, barely passable, sneaks a few hundred meters into the jungle of tall grass. |

|

|

| At the bushes then succeeds a plain rather sullen, cold, sometimes muddy, even marshy in bad weather. But the oily soil, undoubtedly more fertile, to see the fields that extend one behind the other, it should not be visited in rainy weather. You’ll sink into a stubborn mud and take with you a little Velay to the sole of your shoes. |

|

|

| Further on, the GR65 flattens on dirt to reach crops and meadows near Ramourouscle. In front of you, the Forest of the Egg under the mountains of Dévès is outlined. |

|

|

| It joins the paved road at the entrance to Ramourouscle. For us today we are experiencing the first downpour.

We have endeavored to show in this site the stages carried out especially in good weather, having traveled this track several times. But it is also good to show the reality in worse conditions, which often gives slightly different landscapes. Often the pilgrim has no choice. |

|

|

Ramourouscle is home to beautiful stone house, where you get the feeling to put your feet into a land that has frozen since time immemorial. It’s saying everything. Even the Knights Templar walked their boots around here. Sincerely, can you dream elsewhere of a ruin as majestic as this one in the middle of the hamlet?

And what about this old device to shoe oxen, one of the most remarkable of the Way to Santiago? Happy region that has preserved its heritage!

| Whatever their condition, these stone houses give a magical touch to the landscape. Here the farms are often made of irregular and dark basaltic stones, joined by a large layer of clear mortar. Sometimes an old well seems to arise out of another age. |

|

|

| Beyond Ramourouscle, a paved road gently slopes up, for more than one kilometer, under the ash trees, towards Montbonnet. You’ll not cross many cars on the axis. |

|

|

| A little further up stands St Roch’s Chapel, at the edge of the road. |

|

|

| The Romanesque chapel of St Roch stands solitary, like an island of serenity and silence. Built in the 10th century, rebuilt at several periods, the chapel first dedicated to Saint Bonnet, was later dedicated to Saint Roch, who became patron saint of pilgrims. The Santiago track is dotted with chapels attributed to this saint. A hospice devoted to pilgrims, now missing, adjoined the chapel.

Legend has it that the inhabitants of Bains, the little neighboring village where a variant of the road passes, jealous of the veneration to Saint Roch in Montbonnet, decided to take the statue of the saint home. They hoisted the statue on a chariot. On the way, the ox and the donkey who were pulling the cart, refused to advance and put their hoofs on a stone with force until they left an indelible mark. |

|

|

| Montbonnet is located just above, under the ash trees. The slope is a little more sustained up to the bottom of the village. |

|

|

Montbonnet, here is another remarkable village cut in massive basalt and tuff, soft rock resulting from the consolidation of volcanic ash. The village is at the foot of a “suc”.

All Velay region is crisscrossed by what people call “suc” which are actually small, rocky, acute, volcanic domes. If you have passed through Via Gebennensis, you have met a lot of such structure’s before arriving at Puy-en-Velay. As a reminder, they are distinguished from the great volcanoes of Auvergne, which were born of gas explosion that created large craters. Here, nature has been softer. Well! The gas was less explosive, and the lava flows of viscosity, emitted at 700-800 Celsius degrees, accumulated in the form of domes. During the growth of the dome, the lava cooled, becoming brittle, can be slabbed. It was at least very useful to the masons of the time to provide at ease slate roofs to cover the roofs.

| The stone crosses keep the place. They are inseparable from the landscapes you cross. Objects of devotion par excellence, they stand everywhere in the hamlet squares, at the crossroads, as so many processions goals for the Rogations or other parish festivals. A small paved road bypasses the village, dotted with beautiful farms. |

|

|

| Further up, the GR65 reaches the large D589 departmental road. |

|

|

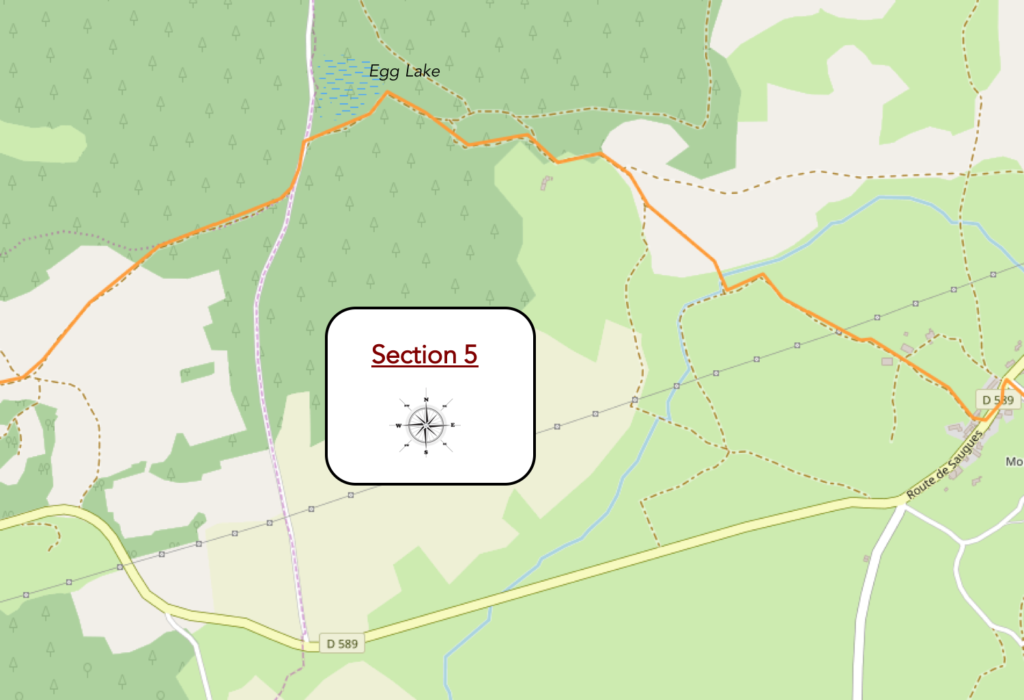

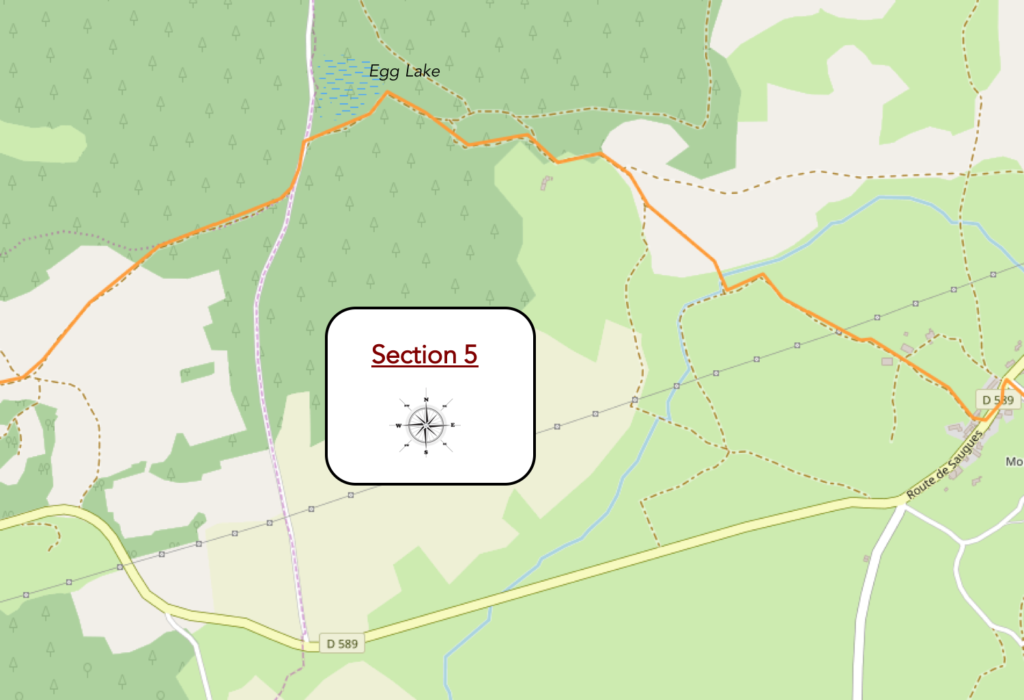

Section 5: Sometimes in the puddles and mud of Lake de l’Oeuf.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: initially easy climb, becoming tough near the forest. On the high plateau, it’s real fun, before the descent.

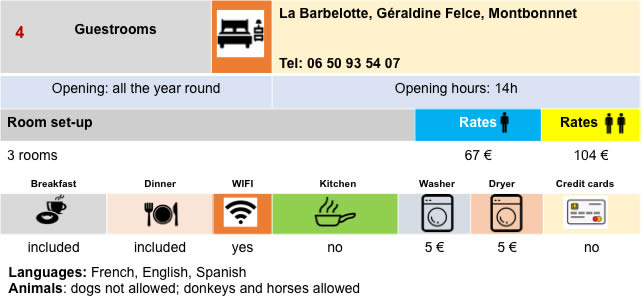

| Along the road, basalt and other volcanic stones are masters of the place. You’ll find housing in Montbonnet. For many pilgrims, it is better to start smoothly. 16 kilometers from Le Puy are enough for their happiness and their legs. |

|

|

| Beyond Montbonnet, a wide dirt road first gently crisscrosses the country. Here the route passes by gigantic horse stables. You’ll gradually get closer to the forest of Lake de l’Oeuf. |

|

|

| The pathway crosses the fields in a small plain, first slightly sloping up, even sloping up a little further. |

|

|

| Here you are at 1’100 meters above sea level, and crops do not grow much. The soil must be quite impervious, as puddles accumulate on the way, even when you are not in a period of heavy rains. |

|

|

| At the place known as Chemin de la Baraque, the pathway starts climbing. Well! Should not we go from Le Puy, located 600 m above sea level, to more than 1200 meters on the Deves mountains? The slope will become tough until Lake de l’Oeuf. The ground is tinged with brown, hints of sands, gravel and tuffs that the water has dripped from the “suc”. |

|

|

| When approaching the forest, the declivity clearly increases to sometimes 20%, alternating between dirt and pebbles. The vegetation is still hardwoods, especially ash trees, hazel-trees, hornbeam and beech bushes. |

|

|

| Then the landscape drastically changes. You reached the woods of Lake de l’Oeuf. The dirt road flattens, under the hardwoods, pines and spruces in large numbers. |

|

|

The highest spot is a place called La Baraque, i.e. the Hut, 1210 meters high, 5 km to St-Privat d’Allier.

A lake, really? Do not expect to find water, it’s just a big peat bog. Again, a magic trick that knew how to execute the volcanoes with great precision. The Lake of the Egg is a flat marshland, a “maar”, will tell you the geologists who know how to give names to all major natural events. Imagine a lot of water under the chimney of the volcano. The temperature rises and the water vaporizes. It’s like a pressure cooker that cannot be controlled anymore. The pressure rises until the fatal explosion. Then, all the volcanic material is projected off with vigor. The “suc” evaporates and the volcanic chimney collapses to leave a big gaping hole. Hard to find water again in such a natural disaster, right? But since that heroic time, vegetation has invaded the lake and peat has formed from dead vegetation. Thus, the plant carpet is extremely flexible under the foot of the walker. Often the pathway is flooded in mosses. In season, it must be covered by yellow chanterelles. After the rainy spring, walkers often walk not on the pathway, but rather in the woods to avoid puddles on the way.

Today, despite a light rain, it is calm here, on a wide dirt road. But, if you walk here in bad weather, expect more sports. After the rainy spring, walkers often cross the woods to avoid puddles on the way. You can see that the water has come back here.

As if you were there after the bad weather.

Wait for the video to load.

| On the Devès Mounts, the atmosphere is clear, very luminous, in the midst of magnificent pines, spruces, brooms, ferns and pink flowers. |

|

|

| You are here on a kind of plateau. The GR65 first flattens on dirt, sometimes puddles. It reaches fairly quickly the place called Les Tourbières. In Les Tourbières, a variant that heads to Les Bains, near Montbonnet, joins the GR65. It is also here that two shortcuts start to reach two lodgings off the road, one in Rougeac, the other in Dallas. Many pilgrims are reluctant to take extra kilometers to stay off the road. But, others like to stroll along the way, all happy to choose housing outside the axes. Another track also travels here, which runs around the volcanoes of Velay. Yet, if you want to spend the night in the two homes mentioned, there is also a shortcut below.

Further afield, the GR65 follows a paved road for a few hundred meters. |

|

|

| Quickly, the GR65 leaves the paved road for a dirt road that steeply slopes down in the lower fields under the pines and spruces. |

|

|

| Further down, the forest gradually clears and hornbeams and beeches grow among conifers. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the slope is reduced for a moment, when the pathway leaves the woods. Here grow some cereal and corn crops near a wooded “guard”. The tar then replaces the dirt. |

|

|

| Near the fields grow elderberries and ash trees, which dominate the other hardwoods in this region. From here, you’ll see extending the imposing terrace of the Margeride. From the top you can see the lines that are the hills of the Margeride. It seems that your eyes embrace the world and yet you see only a flap of Gevaudan, Aubrac and Margeride. The panorama encourages reverie and tranquility, in a limitless horizon. The mounts of Gevaudan and Margeride draw a long black line in the sky, a powerful ridge filled with forests. Do wolves still roam in tormented winters when the snow covers hills and gullies? Two centuries ago, a giant wolf declared war to the human race here. An entire army was opposed to him. Finally, the wolf was surrounded and killed, after many carnages, that’s what people believes.

Down below, flows the Allier River, at the bottom of the valley. Like icebergs in the middle of the ocean, the small mountains of the Margeride have remained granitic and gneissic in the middle of an ocean of lava that descended from the volcanoes of Velay and Aubrac. The Allier River carved here the basalts vomited by Devès volcanoes. |

|

|

| Then the slope is again steeper, at nearly 15%. There is again a shortcut that allows you to reach both lodgings off the road. |

|

|

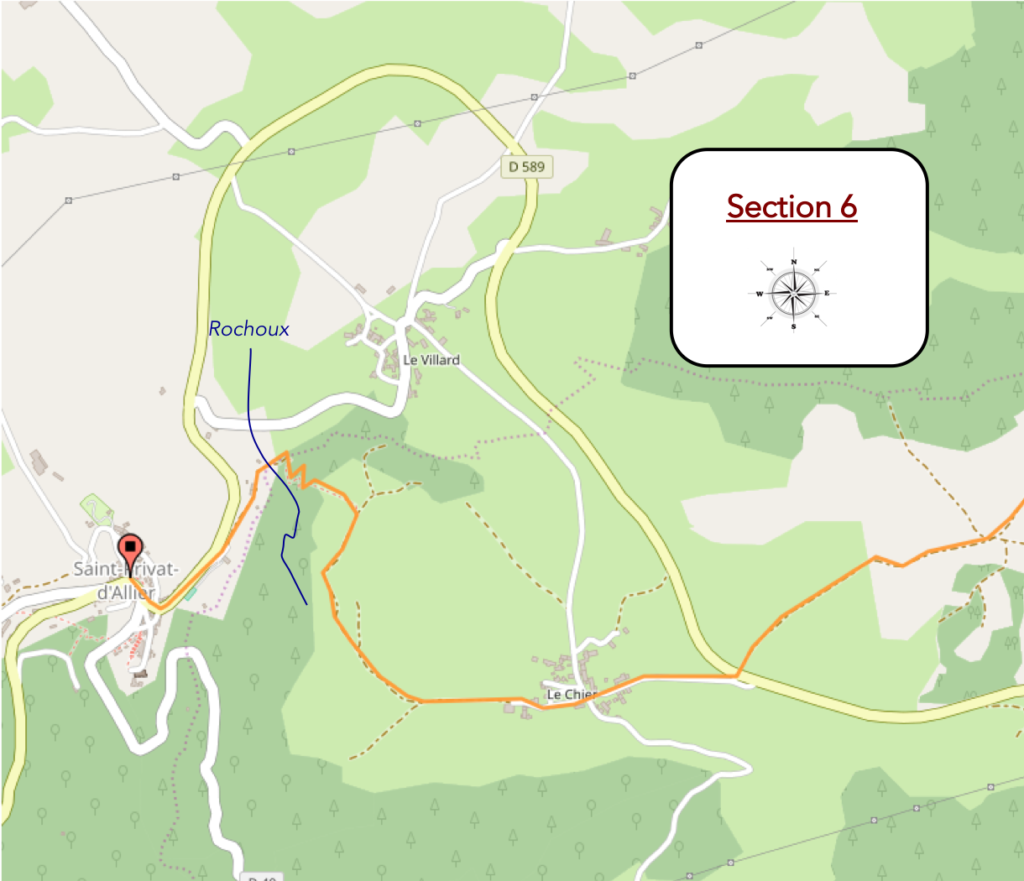

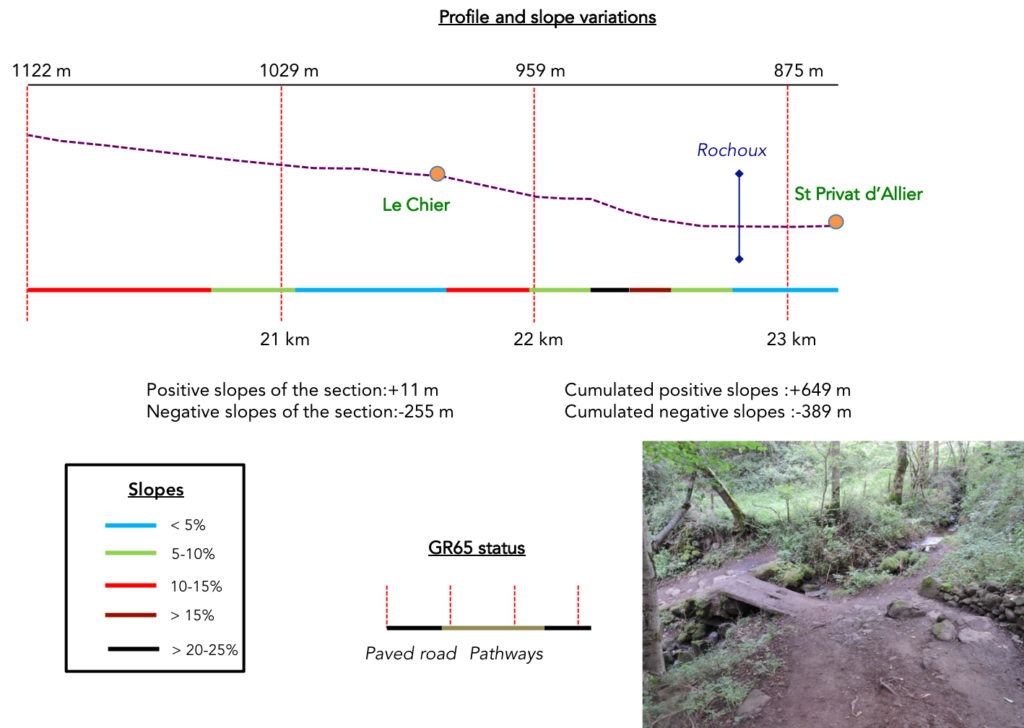

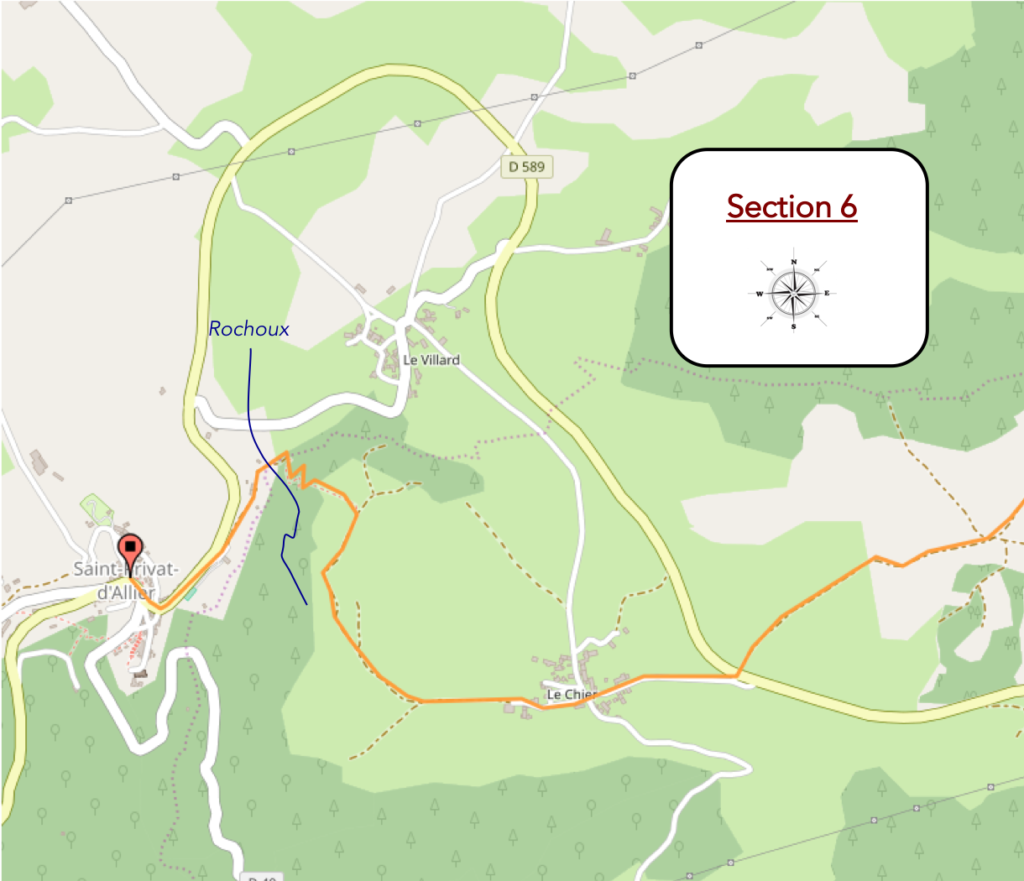

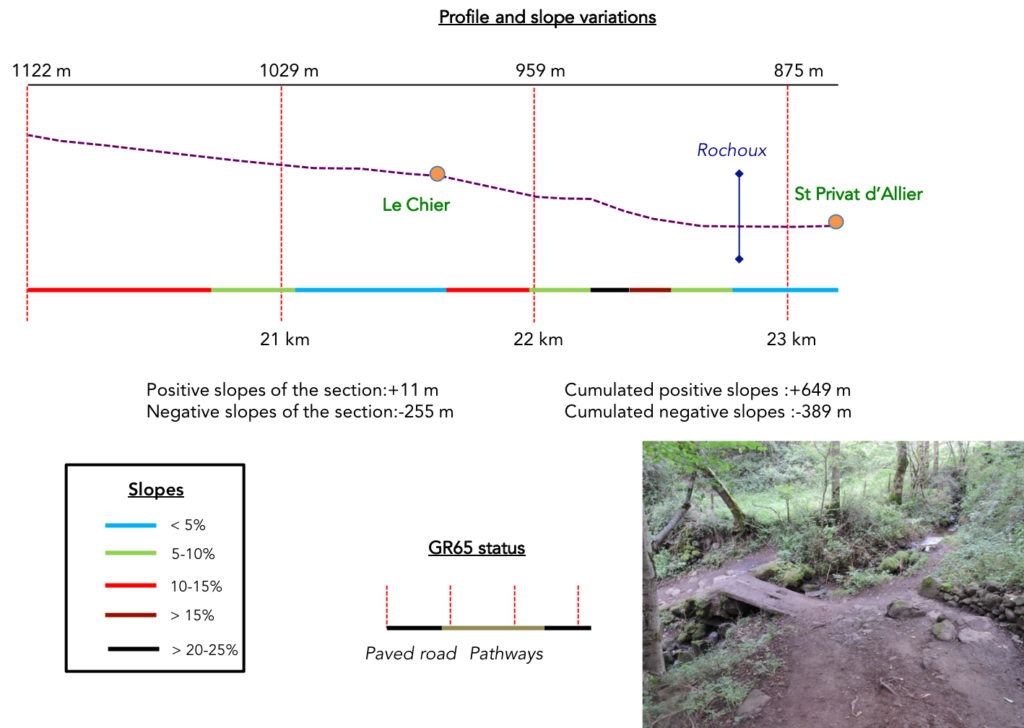

Section 6: An often-demanding descent to St Privat d’Allier.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: sloping downhill to St Privat, it is especially the last section which is demanding, in the pebbles that outcrop and slide.

| The pines sometimes make guards of honor along the way. Here a family has embarked with donkey and luggage. It is often the youngest who has the beautiful role, perched on the mount. We are in the summer, and many families are adopting this way of doing things. Rarer are the pilgrims who travel alone with their donkey. For families, these are often short trips, very organized, because they must leave the donkey someday, somewhere. |

|

|

| Today, the weather is bad and the fog is rising. You will not see below, the red tile roofs of Le Chier, a rustic village, which close ranks in harmony. Further down, the GR65 joins and crosses the D589 road again, just above Le Chier. |

|

|

| At the bus stop, you are 2.3 km to St-Privat d’Allier, 1058 meters above sea level. It will be necessary to descend another 200 meters to reach the end of the stage, which announces a rather difficult course. These bus stops are probably more useful to local people than pilgrims who sometimes find a respite in the pouring rain. |

|

|

| Le Chier, a small agricultural hamlet, is just below the fork. A paved road leads there under the ash trees. Some pilgrims hate the rain, others worship it, except when the rain drips on the forehead. But the villages are just as beautiful, when you can only guess the beautiful frontages that emerge as ghosts out of dense fog. A real time to walk his dog, right? |

|

|

|

|

| In those moments when you have the feeling that the night has already fallen, that you sink further in the fog that creeps everywhere, that your camera is not yet completely fogged, it is better to have some marks to indicate you the way, right? |

|

|

| And often, there is a miracle for worried pilgrims and amateur photographers. You can see that a pathway steeply slopes down in a clearing among pines, ash trees, maples and beeches. |

|

|

| The pathway descends here on a steady but steady slope, sometimes on the brown ground, sometimes on the gray soil … |

|

|

| … until you find another forest lane that is quick to dive into the dale. Here the slope of the pathway really increases, to the bottom of the dale. The stones abound on a bad little lane. In dry weather, this is not a problem except for the knees and joints. In rainy weather, the track can be very slippery, especially since rainwater often uses the track as a stream. |

|

|

| Here is absolute pleasure, in the ambient humidity, in the middle of the roots, rocks covered with moss and lichens, and stones that roll under your feet. But you are in the shade of the big hardwoods. Only oaks and chestnuts are lacking. |

|

|

For your pleasure …

Wait for the video to load.

| Downhill, the GR65 crosses the Rouchoux stream near deserted Pique-Meule Mill. |

|

|

| Not far away, the route joins D589 road and you can catch glimpse of the first houses of St-Privat d’Allier, which stands on a rocky spur. |

|

|

| Today, it is an execrable weather on the village. You will not see anything there. So, let’s transpose ourselves by magic a day of good weather.

At the entrance of the village, you may meet a nice lady who will also remind you that we are in the land of lenses. |

|

|

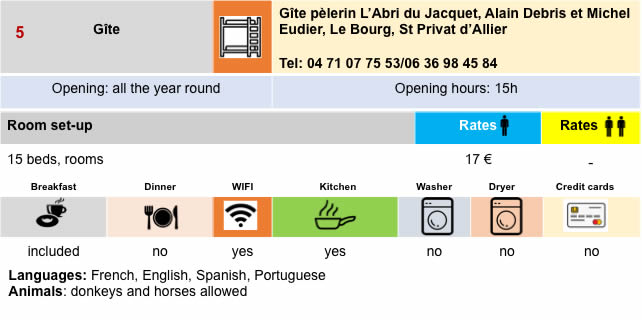

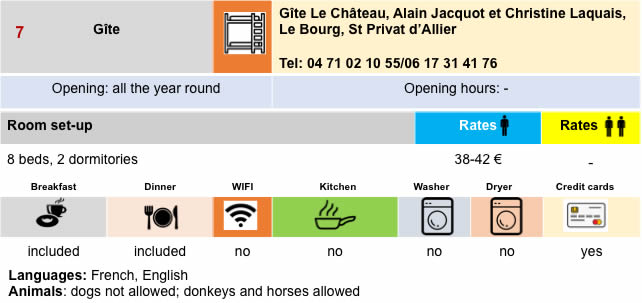

| St-Privat d’Allier is a charming magical village with its old houses perched over the Allier Gorges. Less than 500 inhabitants live here and the village is almost entirely dedicated to Santiago pilgrims. The castle has a long history. It used to belong to mighty Auvergne barons, such as the Mercoeurs, the Montlaurs, amongst others. It was destroyed and rebuilt in the XVIIIth century and later plundered when the revolution broke out. It was then taken over by nuns and turned into a school which closed up in 1988. The Roman church, which probably dates back to the XIIth century, was renovated in the XVth century. The castle is now a private estate that cannot be visited. Yet in recent years the castle enjoyed a revival as signs at the entrance still demonstrate. But, today, that time seems to be gone. |

|

|

Local gastronomy

At the evening meal, you will often find the truffade, a traditional dish of Auvergne, a mix of potatoes and fresh cheese (called ‘tomme’). The potatoes are cut thin and browned in fat (bacon or sometimes oil) and garlic until they are tender. Then fresh Cantal ‘tomme cheese’ is added and mixed. This dish is often eaten with a salad.

They may also serve a Velay farmer cheese, a cheese matured two months by tiny mites, artisous, which give it all its originality. Enjoy your meal.

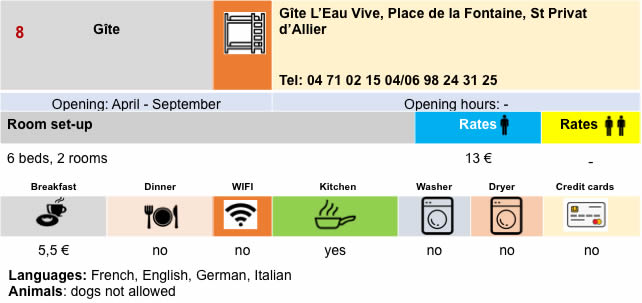

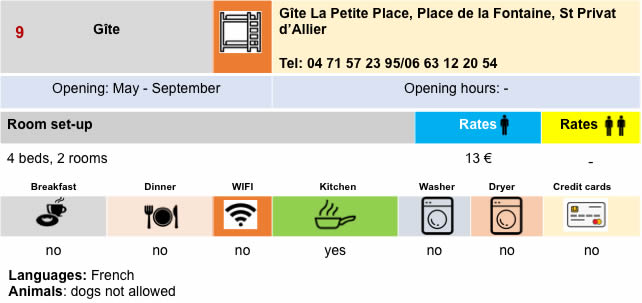

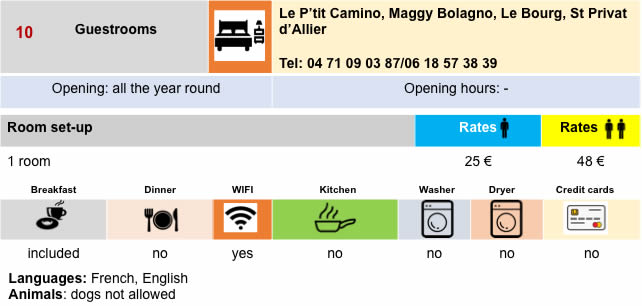

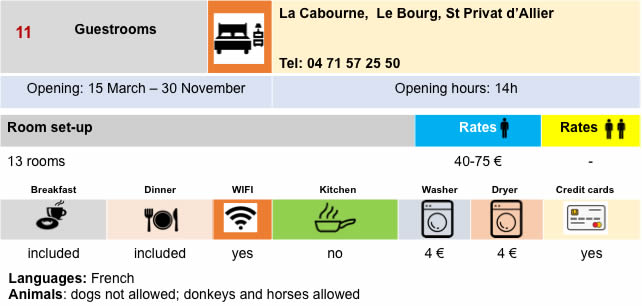

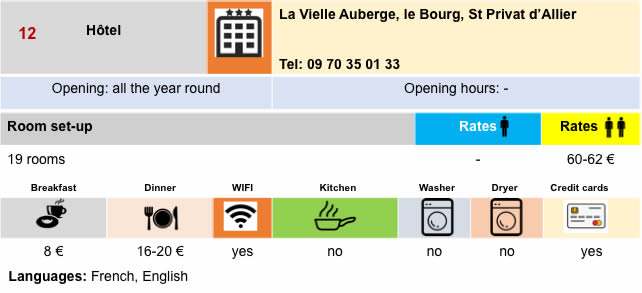

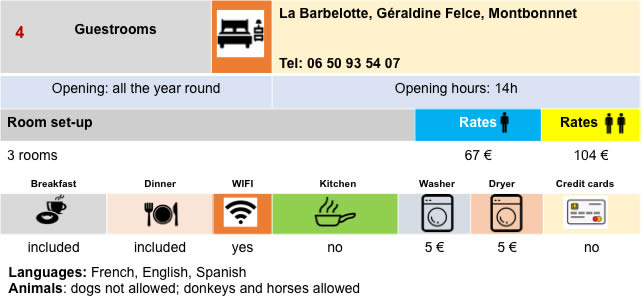

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 2: From St Privat d’Allier to Saugues |

|

|

Back to menu |