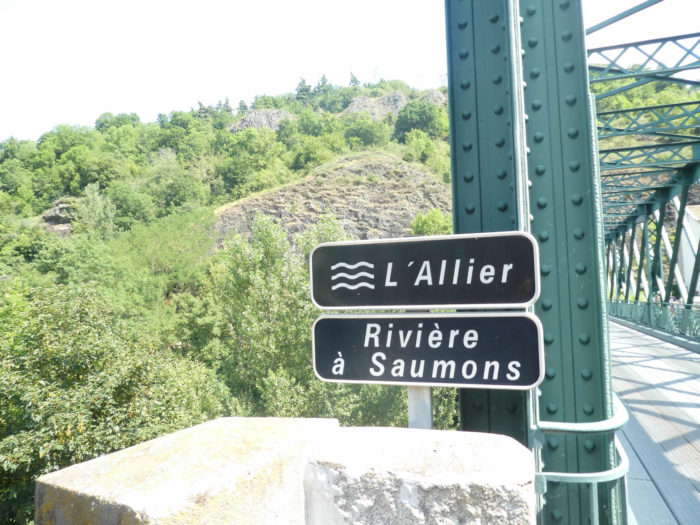

Under the Eiffel Bridge flows the Allier River

DIDIER HEUMANN, MILENA DALLA PIAZZA, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

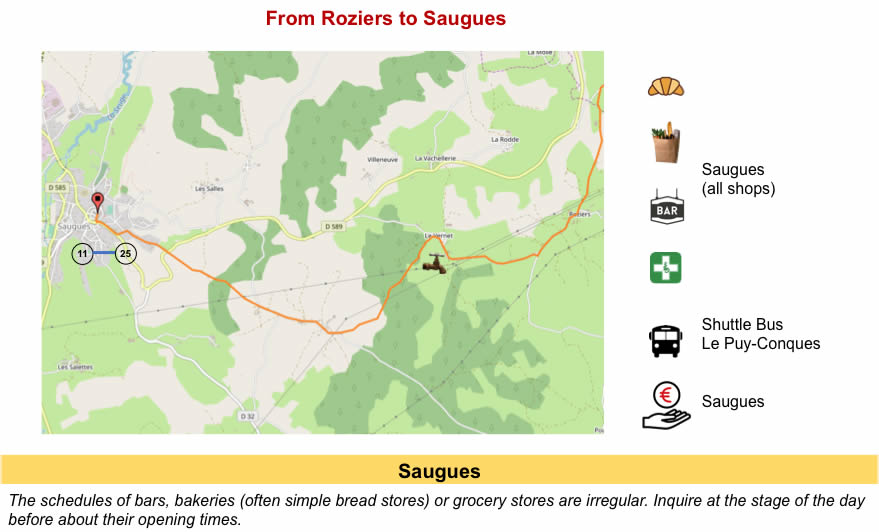

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the roads. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-randonnee/de-st-privat-dallier-a-saugues-par-le-gr65-29678071

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in France without an Internet connection. Therefore, you can find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the book title to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

Allier Gorges are the natural border between dark basaltic Devès in the east and gray granite Margeride in the west. Today you’ll be walking in Haut-Allier, a transition country between the mountains of Velay and Margeride. The Allier River is a wild stream that offers a stunning mix of magnificent sceneries of breath-taking cliffs overhanging a deep valley.

The GR65 heads southwest from St Privat d’Allier and crosses the Allier basin. The whole stage is in Haute-Loire. Nature is pretty rugged here. The stage may seem short, about twenty kilometres long. It is nevertheless challenging. Between Loire and Allier, on the slopes of Mount Devès, volcanoes have spread their lava flows modifying the river beds. They have modelled the landscape, sometimes to create deep cuts and very narrow valley bottoms, as at Monistrol-d’Allier. The Allier River carved in the granite of Margeride, the oldest rocks of the Massif Central. The complex meanders of the Haut-Allier are the result of the efforts made by the river to bypass the obstacles caused by the Devès volcanic flows coming down to block the river bed.

Thick coniferous and hardwood forests have covered the less exposed slopes of the valleys. Pine-trees, beeches and oaks are common, sometimes willows and alders near rivers. The Allier River is, in some places, almost inaccessible. On the other side of the valley, meadows or moors of heath and broom have carpeted the basalt cliffs and the basements, forming balconies suspended over the river, allowing the men to settle down. The villages, small and isolated, hesitate between the matte basalt and the shiny granite. The railway also marks the valley. The train Paris-Marseille, called the Cévenol in 1955, crosses the Haute-Loire by the gorges of Allier River.

|

Before taking the road, a word of geography. Rivers are integral part of the landscape on your way. As you will follow or cross many of them, let’s get into some details. From this region of confrontation between the granite of the Massif Central and the basalt flows that the volcanoes vomited, great rivers of France were born here. It is curious to note that very large rivers of France have their sources in a region of small mountains. Loire, Lot, Allier, Truyère, all these rivers were born south of Velay and in the Cevennes Lozère, near Mende. The Allier River, near which you’ll be walking today, has its source in Moure de la Gardille, then flows north, through Brioude, Issoire, Clermont-Ferrand, Moulins and Vichy, to empty into the Loire near Nevers. It should also be noted that this region is the watershed between the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. In fact, only the Ardèche River flows in the Mediterranean basin. Lot, Tarn, Allier Rivers, but also smaller rivers like Bès or Truyère have their source in Lozère. The Loire River is born a little further east.

|

|

|

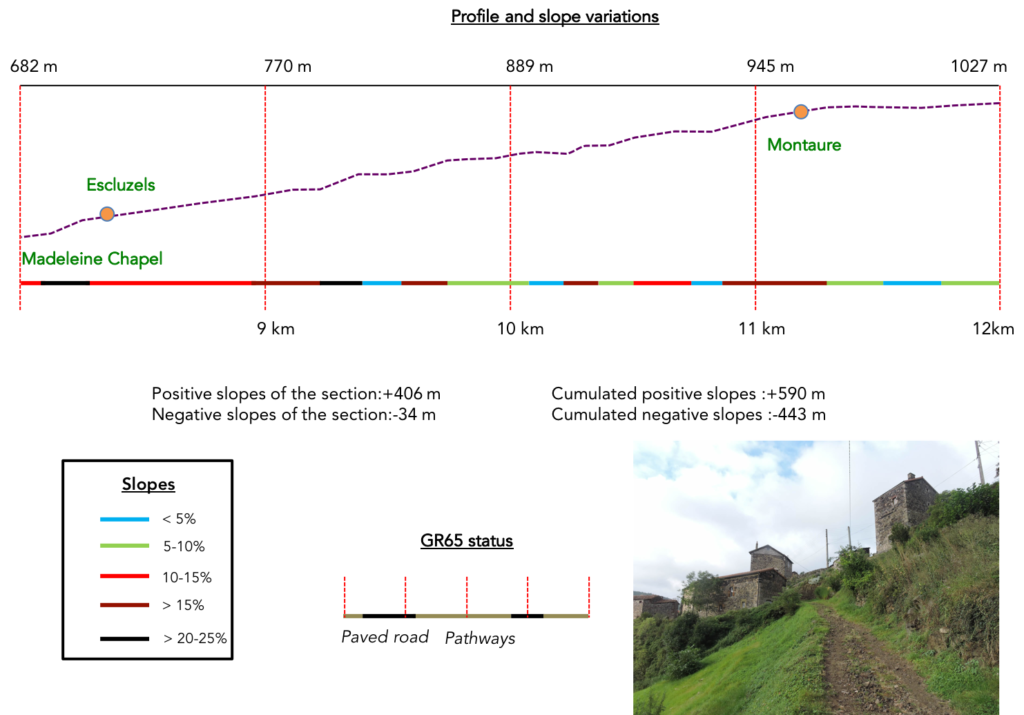

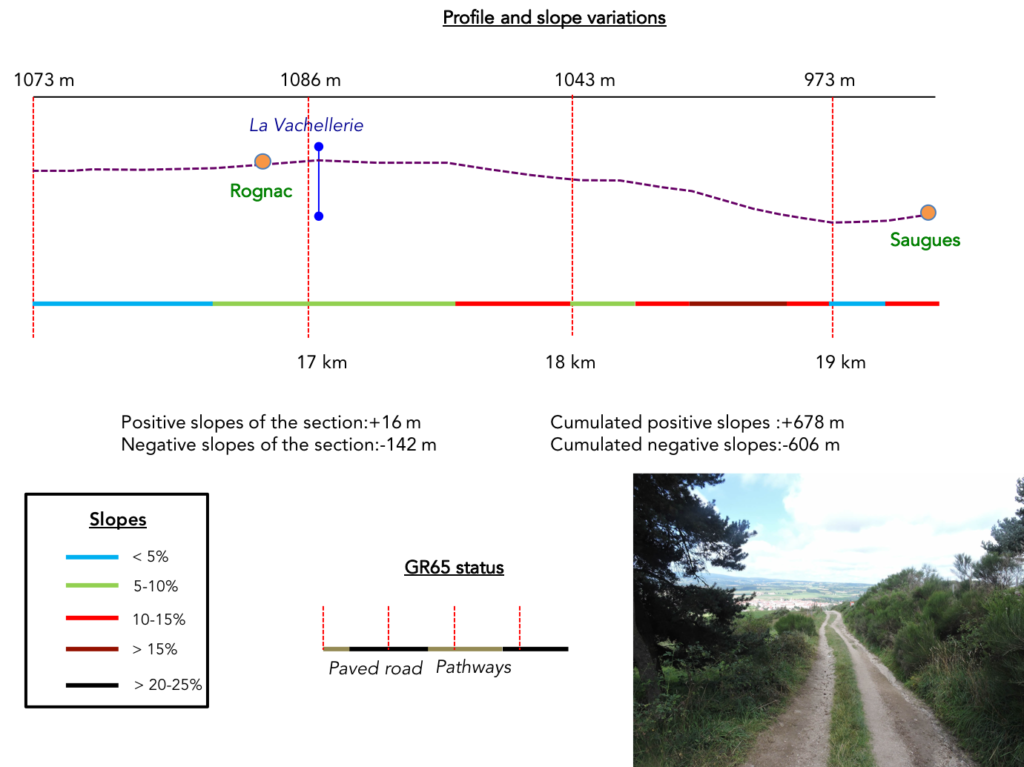

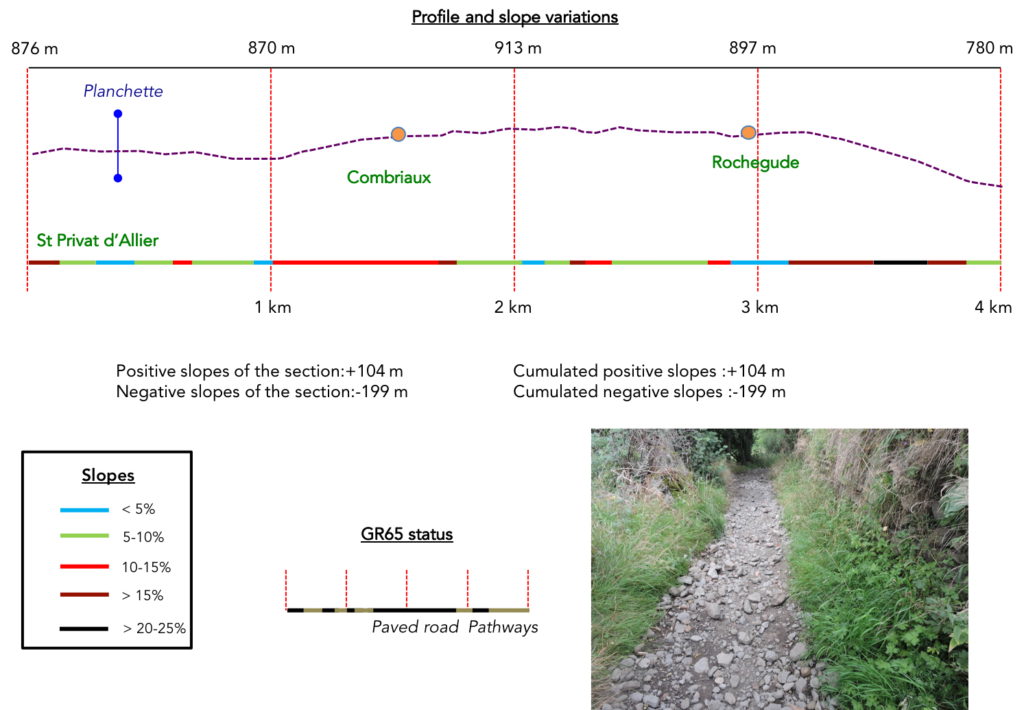

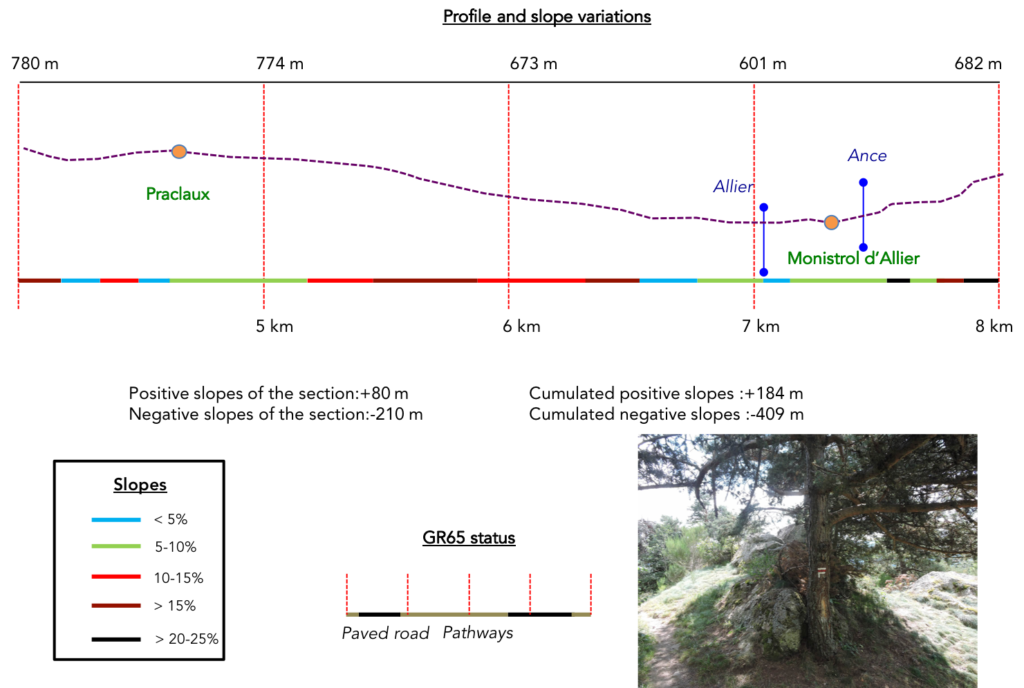

Difficulty of the course: The stage is short, yet demanding, with large slope variations (+678 meters/-606 meters) for a short track. The journey starts with a slight climb to Rochegude village. Below you can look out over the impressive fault of Haut-Allier deep valley. Beyond Rochegude, the track slopes steeply down on rocks and roots to Monistrol, where it crosses the Allier River. While sloping down to Monistrol, you cannot help seeing in front of you Escluzels overhanging the cliff. And it’s true! Some argue that the short climb to get there is one of the most challenging efforts of Camino de Santiago. Beyond Escluzels, the GR65 climbs to reach Montaure. Fairly soon, it flattens to enter Gevaudan, the “country of mysteries”, a Margeride region, long haunted by the terrible “Beast of Gevaudan”.

Passages on paved road or hiking trails are broadly similar:

- Paved roads: 10.0 km

- Dirt roads: 9.2 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on Via Podiensis. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

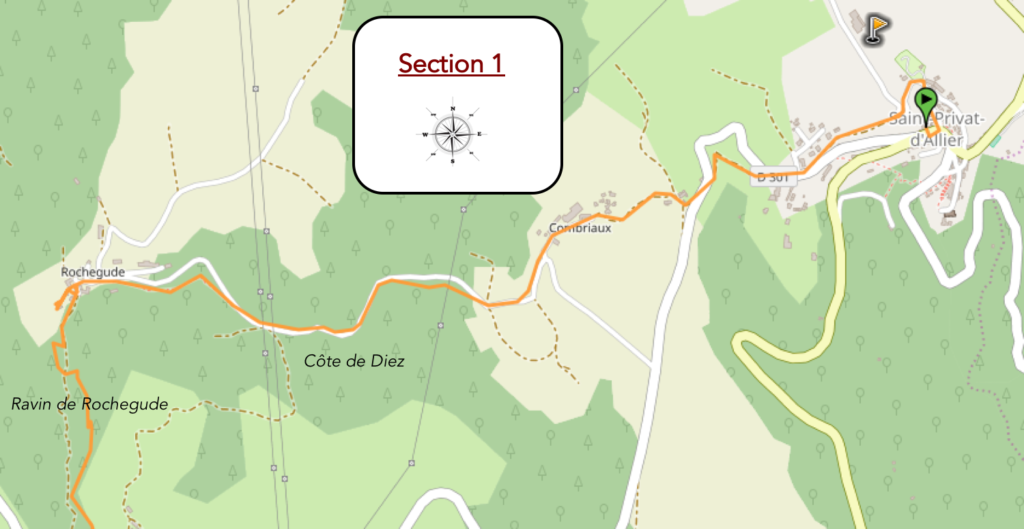

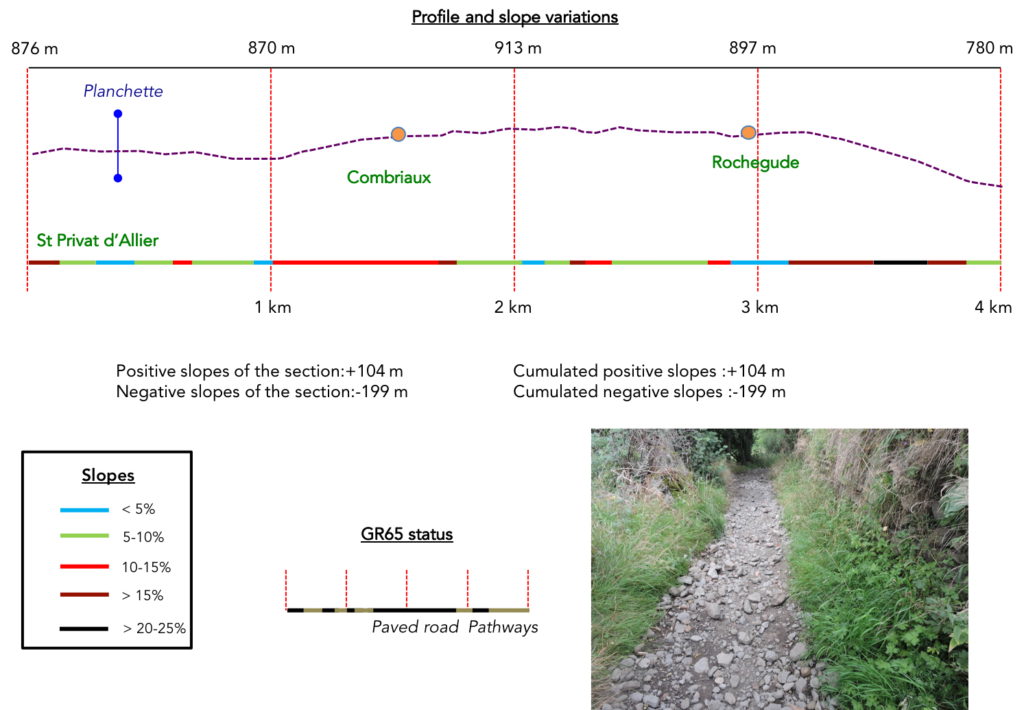

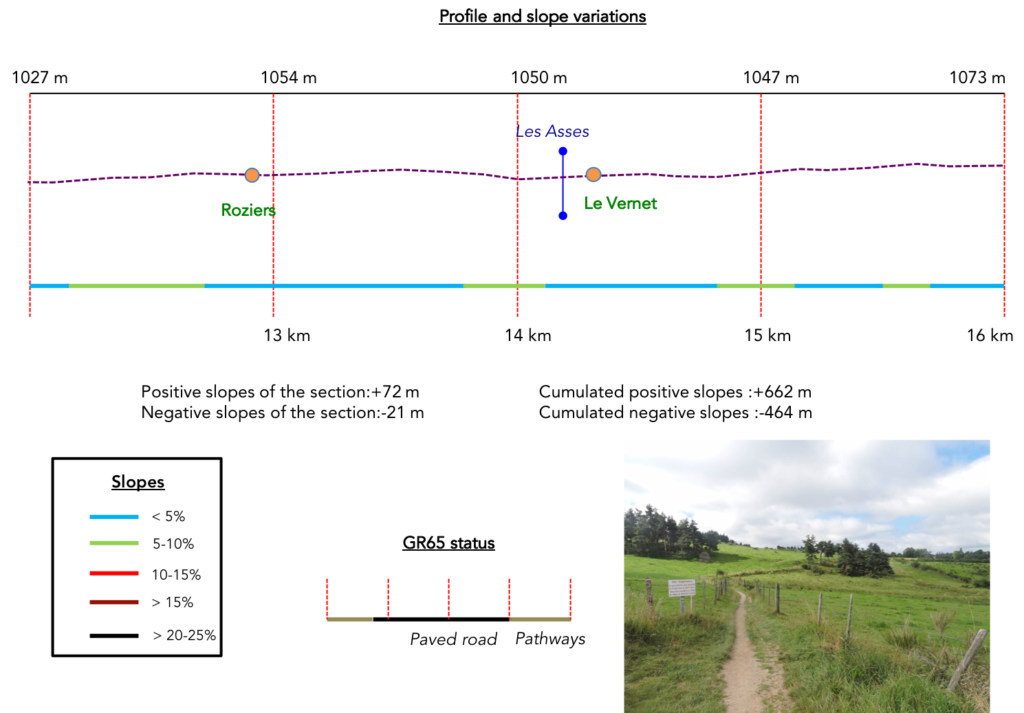

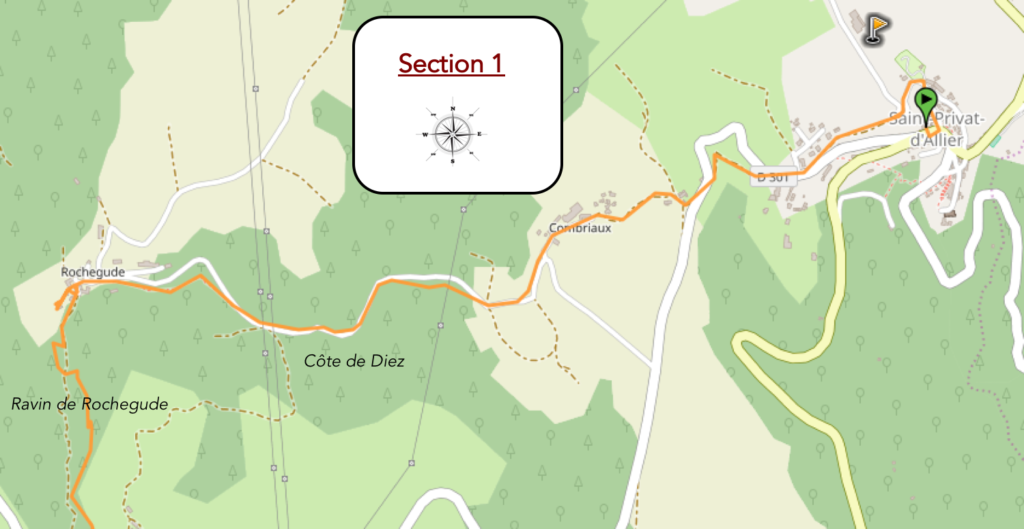

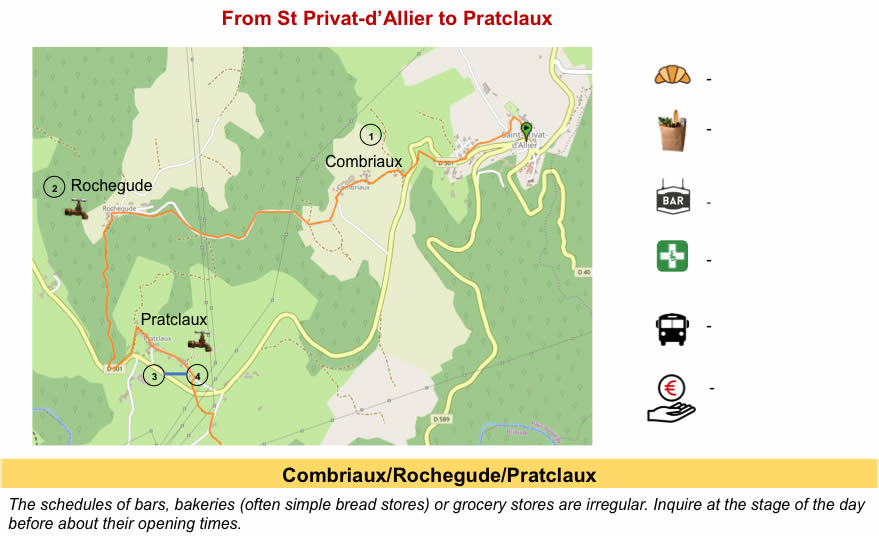

Section 1: On the hillside before “plunging” to the Allier River.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: sloping down, up is everywhere here: uphill above St Privat, then intermittently to Rochegude, then steeply down to Pratclaux.

|

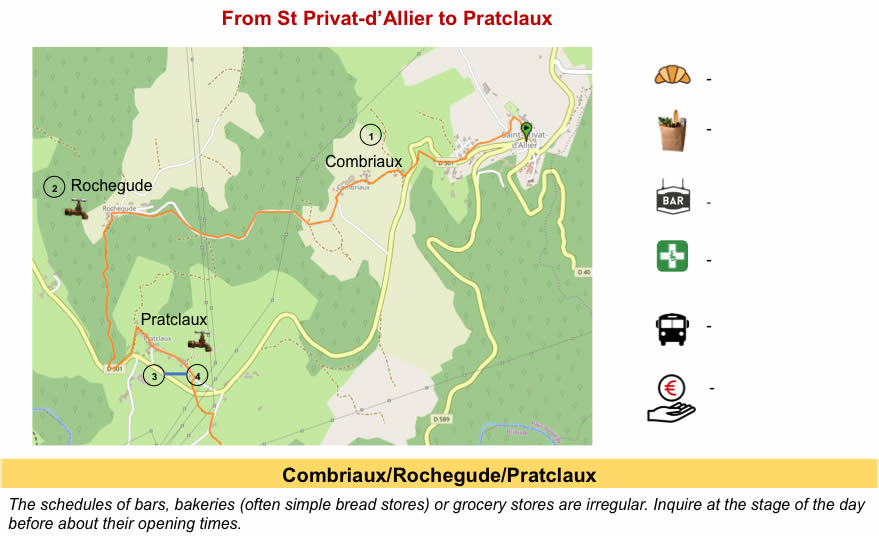

The GR65 bypasses St Privat d’Allier alongside hill, probably to enable you to better admire the village from above or allow you to look over the exuberant hole of the Upper Allier valley below. The St James’s track likes making jokes. Because, shortly after, it runs even downward back to the exit of the village to join a small road, smoothing out of the village to Combriaux.

And above the village, there is not much to see. You can simply leave the village by the paved road that heads to Rochegude Chapel and join the GR65 at the exit of the village. |

|

|

|

|

|

Insensibly, you leave the Velay region for another universe, that of Margeride and Gevaudan. However, walking is not changed. It must be done, the Camino de Santiago has its own rule: every climbing follows a descent which itself generates a new climbing.

A few hundred meters further, it’s the same story. The GR65 leaves the paved road to steeply sloping down in a bad small lane on unpleasant stones, which can be very slippery in case of rain. A sign announces that it is better to give it up in wet weather. All that story to soak your feet in the worthless Planchette brook, then climbing up again steeply to the road. Do not hesitate here. Follow the road.

|

|

|

| Whether you have sloped down to the stream or followed the road, further the GR65 leaves the paved road to steeply climb towards Combriaux hamlet. |

|

|

| It is a stony lane that you will encounter in a woodland dominated by beeches or hornbeam shoots. At the exit of the undergrowth, the pathway gets to Combrieux. |

|

|

| Combriaux is a handful of massive houses built with volcanic stones. When you hear “volcanic rock”, you imagine a dark rock. These dark rocks, they are called basalts in the broad sense. It’s simplification, because even the basalts include a family of rocks very varied. In addition, many volcanic rocks are clear or take various hues, far from the idea that one is made of it at the beginning. Tufts, dacites and trachytes, seen here in the midst of black basalt stones, are a good example. If you see these houses from a distance, you could even imagine that they are made of limestone, which is not the case. |

|

|

| Behind the last houses of a hamlet that seems almost deserted, a pathway continues to climb in the undergrowth, in the hazel trees and the hornbeam bushes. |

|

|

| At the top of the climb, where you’ll see more and more conifers, the pathway joins in the broom the small road that leads to Rochegude. |

|

|

| It’s always the same old tune. The road heads uphill to Rochegude. There is virtually no vehicle. Only a few mushroom pickers haunt these places. But no! The route makes constant yoyos, at the top of the road, at the bottom of the road, on the road. If you like exercise, take the pathway. Otherwise, follow the road. The two tracks lead to the same place, in Rochegude. If you follow the road, a wide grassy strip will allow you to avoid the tar. Do as you wish. |

|

|

| Whatever will be your choice here, you will not avoid a little further to find yourself on a small stretch of tar. Further ahead, the pathway runs over the paved road. Just for a change. |

|

|

| Whether you walk on the dirt road or on the paved road, it is always the forest you cross. The Haute-Loire is a very wooded department, with 40% of the territory covered with forests. There are 75,000 forest owners in the Haute-Loire, and 90% of the forests are private. Some people even say that they do not even know they own it.

So, a little ride on the dirt road, before finding again the paved road. |

|

|

| So, en route to a bit of tar, then again, the dirt road, this time again below the paved road. To change again. |

|

|

| The forest is dense here. Tall beech trees compete with oaks, pines and spruces. For many people, hornbeam and beech, it’s the same tree. It’s a bit true. But if you have the eye advised, you will see the difference, especially at the level of the leaves, less at the level of the trunks. Here both species coexist. It’s the same for spruce and fir trees that look alike, but if you see cones on the ground, they are spruces, not fir. In this forest you will see mainly spruces, the big white fir trees and Douglas fir are rarer. And all this big world talks with the moss, the big ferns and the crazy grasses. The dream for mushrooms, no? |

|

|

| Shortly after, the pathway leaves the forest and arrives near a picnic place and a dry toilet at the entrance to Rochegude. |

|

|

Rochegude is a stone’s throw away, a former fortified village that has long played the role of advanced sentinel to detect potential enemies coming from Gevaudan region.

Rochegude is home to a few stone houses leaning against the mountain. You can search at your ease the open mouth of the barns, trying to discover behind a window or in a garden any sign of life. You will rarely come across a human presence in these hamlets that seem mostly deserted. A leaden silence hangs over the roofs, disturbed only by the gurgling of a fountain, whose water is not always drinkable. You will probably have more chance to meet other pilgrims like you, stopped for the picnic. The houses are practically welded to each other, huddled and curving under the power of the mountain that overlooks the village.

| Yet, there was a time when Rochegude was teeming with people when it played its role as sentinel. Rochegude could derive its name from “roca aguda” (acute rock). Formerly, the dungeon, attested to 1255, was the property of the Auvergne family of Montlaur. Only a tower remains of the castle which was a stop for the pilgrims of Compostela in the Middle Ages. The tower, vain but touching of distress, still rises on a rocky needle which overhangs the gorges of Allier River.

A tiny chapel dedicated to St James, perched on top of rocky belvedere, also dominates the hamlet. Beware of straying too away in foggy weather, as they are steep drops in the area. |

|

|

| The view over the Haut-Allier is breathtaking. The horizon is barred by endless forests. The space opens on the Allier gap, with its high cliffs and its strangled valley. Opposite, it will be necessary to climb soon to leave the defile of the Allier River. |

|

|

| Beyond Rochegude, a narrow lane severely plunges into the dale (more than 100 meters of altitude difference) in the rocks and the roots. At the beginning, the pathway descends under the chapel in the bushes, the ash trees, along the low walls and brambles. |

|

|

| Further afield, you’ll see the pines, oaks and beeches appear when the pathway approaches the vertiginous descent, with slopes in places exceeding significantly 40%. |

|

|

| The forest is beautiful here, terrifying some say. The dale becomes a gorge, sometimes even abyss, wild defile. The trail meanders through wind-blown, multi-century-old pine trees along granite bars covered with moss. Even maples and chestnuts, rare in the region, do not want to be let down. All around, coppice is bushy, sometimes inextricable. |

|

|

Sometimes, even the pine trees seem planted on tortured granite slabs.

It’s only happiness, of course…

Wait for the video to load.

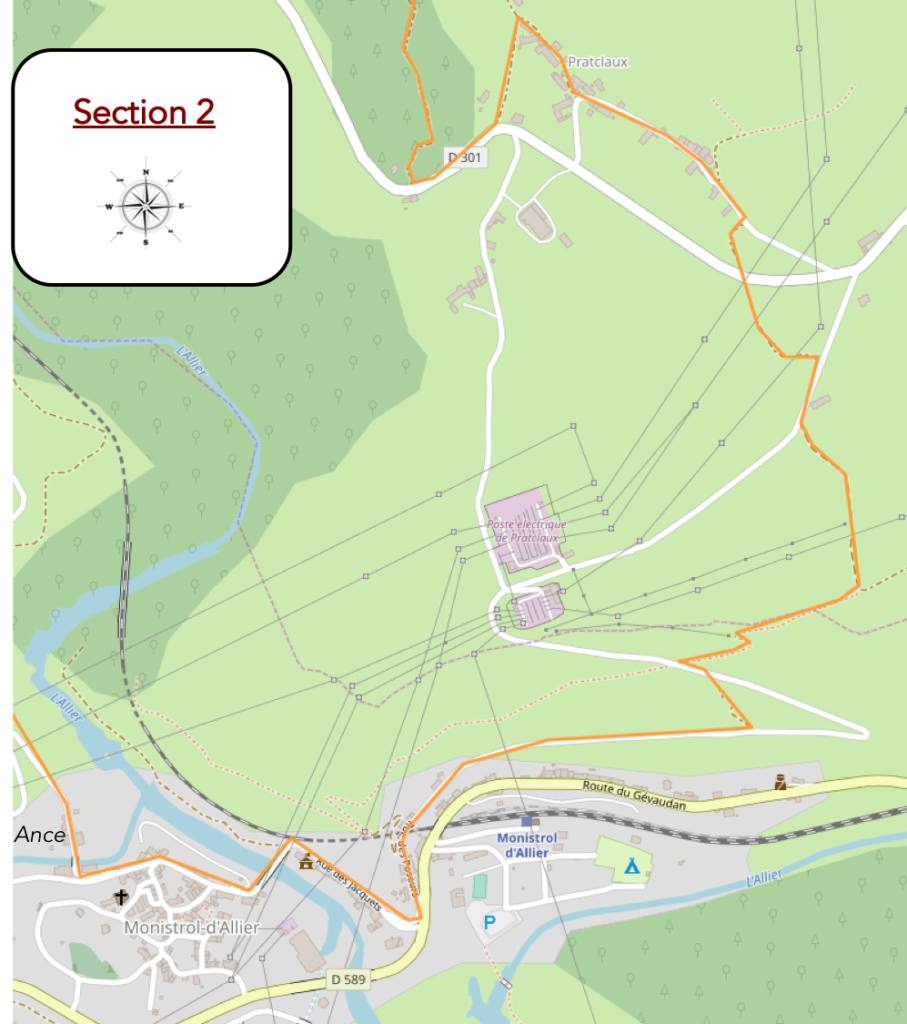

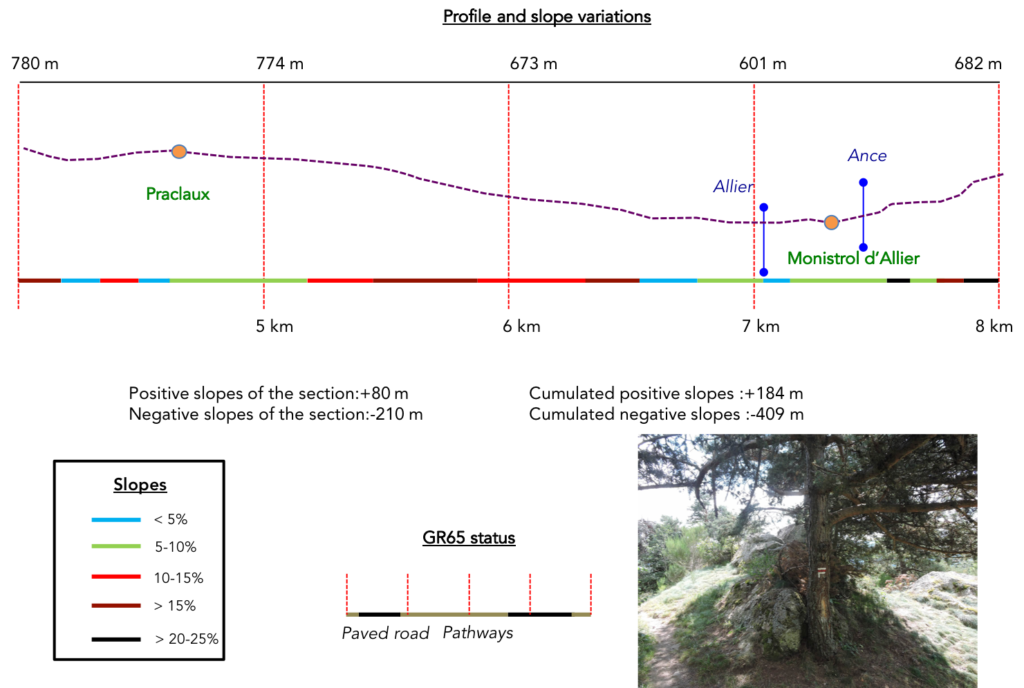

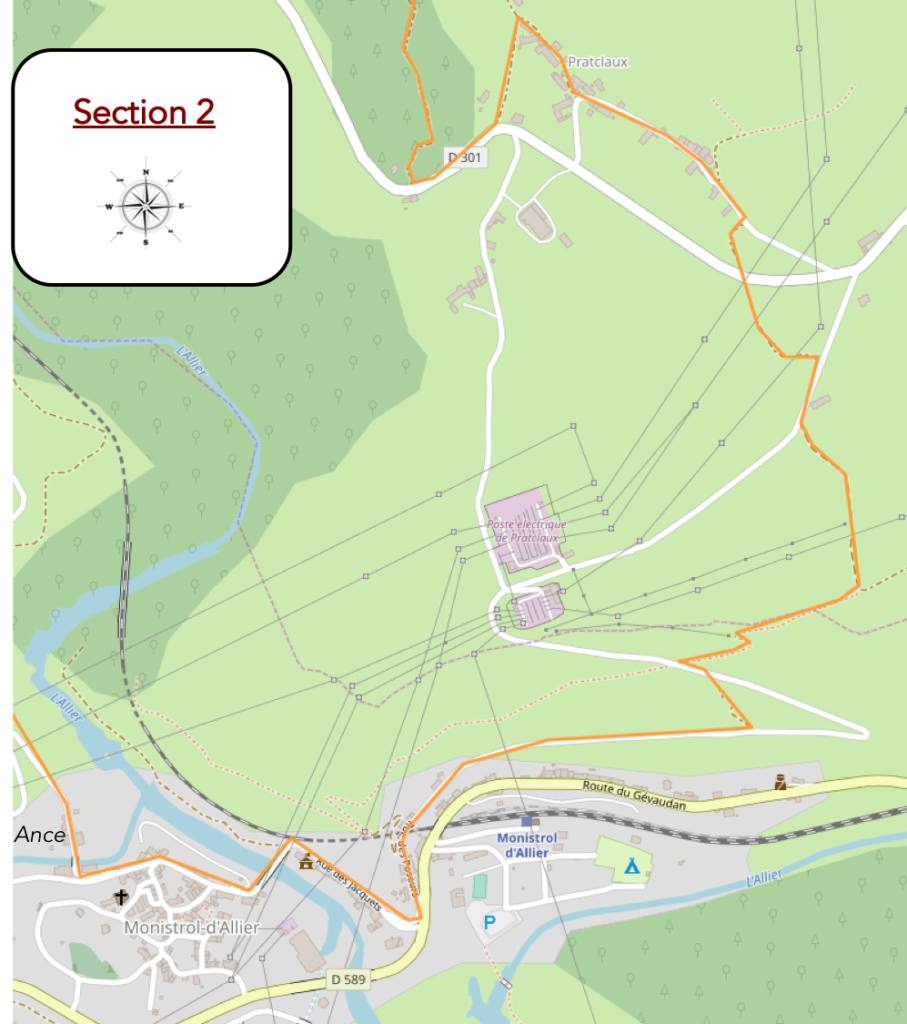

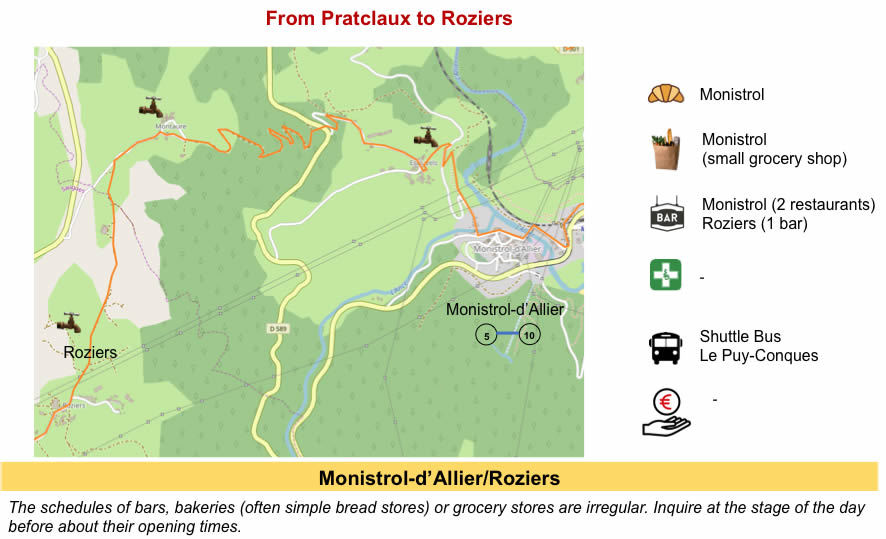

Section 2: Before a very demanding effort on St James’ track.

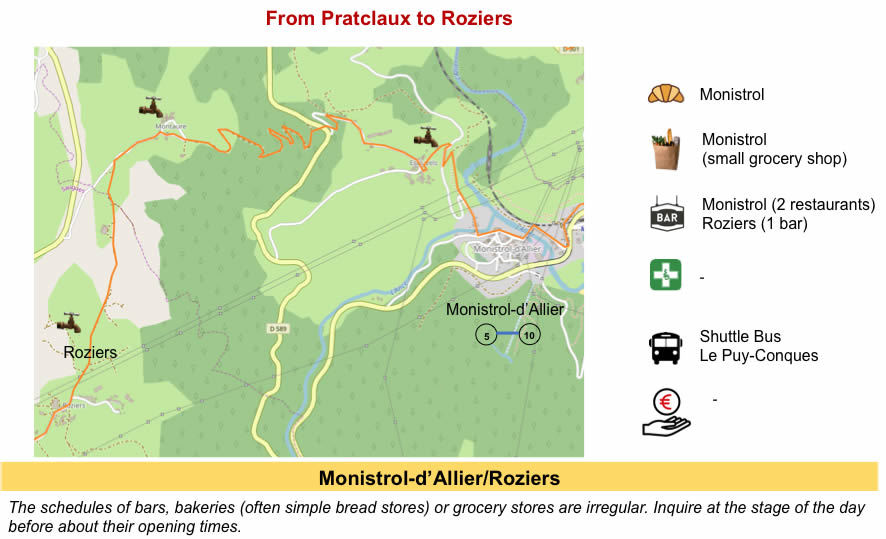

Overview of the difficulties of the route: at the bottom of the difficult descent to Praclaux, some ups and downs without problem, and the slope becomes more tough approaching Monistrol d’Allier. As soon as you leave the village, starts the steep climb to Escluzels hamlet.

| Sometimes the slope seems to be reduced a little, but modestly. The lane continues sloping down, sometimes on the dirt, sometimes on the granite itself. |

|

|

You’ll reach the end of the pleasure ……

Wait for the video to load.

| There are many pilgrims who utter a great sigh when they see at the bottom of the descent on a last difficult granite ramp the small paved road that passes underneath. |

|

|

| At Pratclaux, you are half way down. The rocks give way to the countryside. The GR65 flattens first on the tar, then climbs up to visit the hamlet, passing in an alley of high ash trees and majestic maples. Here again, if you are in a hurry, you can continue on the road. You will take back the GR65, which comes down a little further beyond the village. |

|

|

| But you will miss the massive houses where the volcanic stones burst. Nobody, or not a lot of people at first sight, has to live here, behind closed shutters. |

|

|

| By the way, is that so true, to see the car fleet? In France, some peasants, art lovers presumably, have taken the detestable habit of erecting these ephemeral monuments along the roads. |

|

|

| Further afield, the GR65 joins the former paved road and crosses the plain through a grassy lane, sometimes mired in bad weather. There are few crops here, in the countryside dominated by high pylons. |

|

|

| Then there is a narrow pathway in the tall grass, a passage difficult to pass in bad weather. The big trees have almost disappeared and only rare ash trees remain in the wildness. Fortunately, the passage is brief, and the pathway finds the road again that descends from Praclaux to Monistrol d’Allier. |

|

|

| A few tens of meters on the tar and, at the corner of a majestic stone farmhouse, the GR65 finds again a dirt road. A small family here makes a piece of Compostela track. The donkey must have suffered before in tall grass. The little girl has taken her place on the pack, and the other children are pushing their jaws tight, perhaps waiting for their turn. |

|

|

| A wide dirt road then crosses the plateau. Further afield, the fields diminish, fraying. |

|

|

| At the edge of the plateau, the lane dives again towards the bottom of the dale. From here, the slope will become demanding, sometimes more than 20% inclination. There are big stones on a difficult track, in the middle of the bushes. |

|

|

| In these soils where the gravel reigns, the soil is so poor that only small stunted oaks grow. The ash trees have melted. |

|

|

| Further down, the bad pathway joins the road of Praclaux to the place known as Le Vivier, nearly one kilometer to Monistrol d’Allier. |

|

|

| The GR65 follows downward the sloping road, which makes a big bend shortly afterwards. |

|

|

| Quickly, you’ll see the village below. The small village of Monistrol is hidden on the edge of the river, at the entrance to a deep gorge. Just follow the straight paved road under the oaks and the beeches. |

|

|

| The road arrives above the village. Below you can see the railway line. As amazing as it sounds, you can take the train here. The Cévennes railway line, which runs from Clermont-Ferrand to Nîmes, passes here. |

|

|

| The road slopes down to cross the Allier River at the back of the gorge. You’ll see Escluzels opposite, where you have to climb up very soon. |

|

|

| Monistrol d’Allier is a gem of a village, astride Allier River. Unfortunately, it is also a dam and a power plant. The village, surrounded by steep gorges, stretches along the river in a difficult to access area. Road, rail, and river meet here. The railway line of the Cévennes, from Clermont-Ferrand to Nimes, runs here. D589 departmental road does not go through the village, passing over a new bridge over Allier River. Another bridge leads to the village. In 1887, a year before the construction of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, Gustave Eiffel built here an elegant green metal bridge. |

|

|

| The village, which is hardly more than 200 inhabitants, is nestled in beautiful stone houses along Allier River and its cliffs. The parish church is of Auvergne Romanesque style. |

|

|

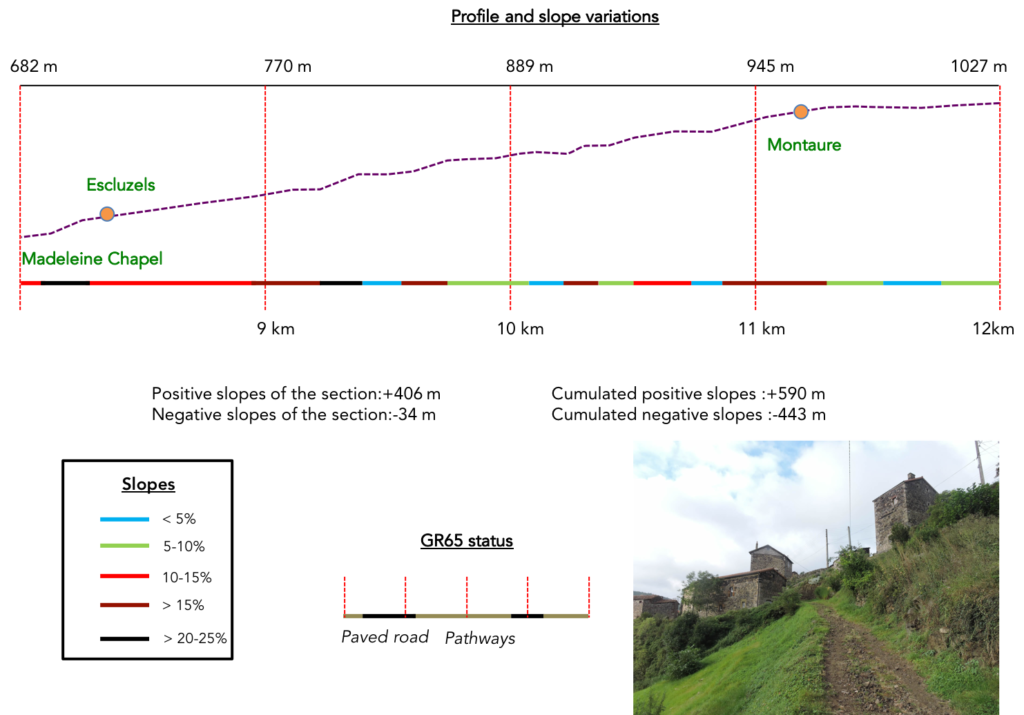

| Beyond Monistrol it is an almost continuous climb of 6 kilometers to Montaure. The exit of the valley is described as a difficult test, among the most demanding of Via Podiensis. What a pleasure! Here, for starters, more than 150 meters of climb over a kilometer to Escluzels, sometimes with slopes barely bearable for retirees. Here, no ripples of terrain, it is only the climb on the tar, then on a stony pathway along the edges of the gorge.

At first it does not seem like anything. You’ll cross the Anse River, a small river that empties into Allier River. |

|

|

| A light appetizer is offered in the form of an asphalt ramp where a dirt lane leaves the paved road on which few vehicles must circulate. |

|

|

| A lane steeply zigzags on the edge of the cliff, on large pebbles that slide under the foot, in the middle of bushes, stunted oaks, ash trees, beeches and chestnut shoots. Yet, there is no danger here, even if the pathway runs by the edge of the cliff. |

|

|

The trail offers a vertiginous panorama, overlooking the valley, the village, its bridges, the waters of the Allier Rver at the bottom of the gorge, and the gigantic forests on the opposite side of the valley.

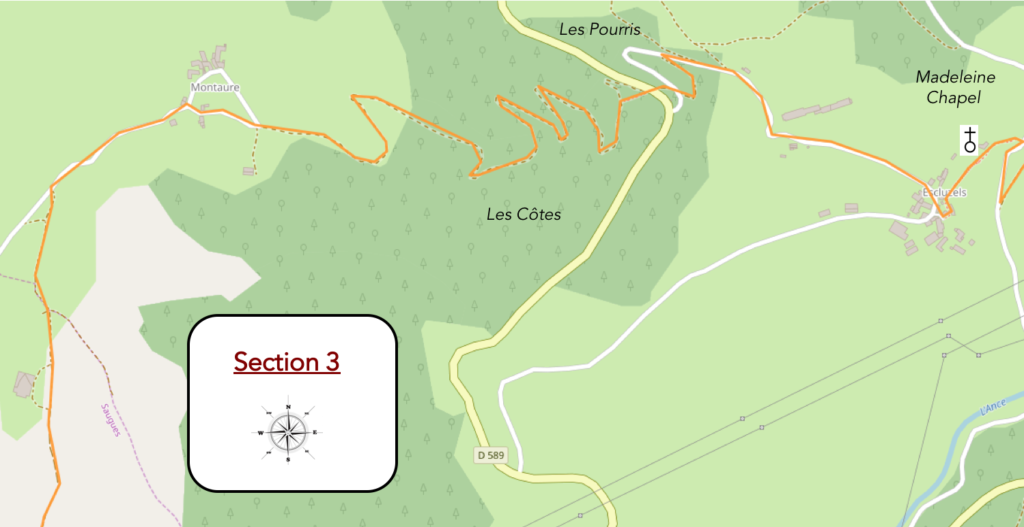

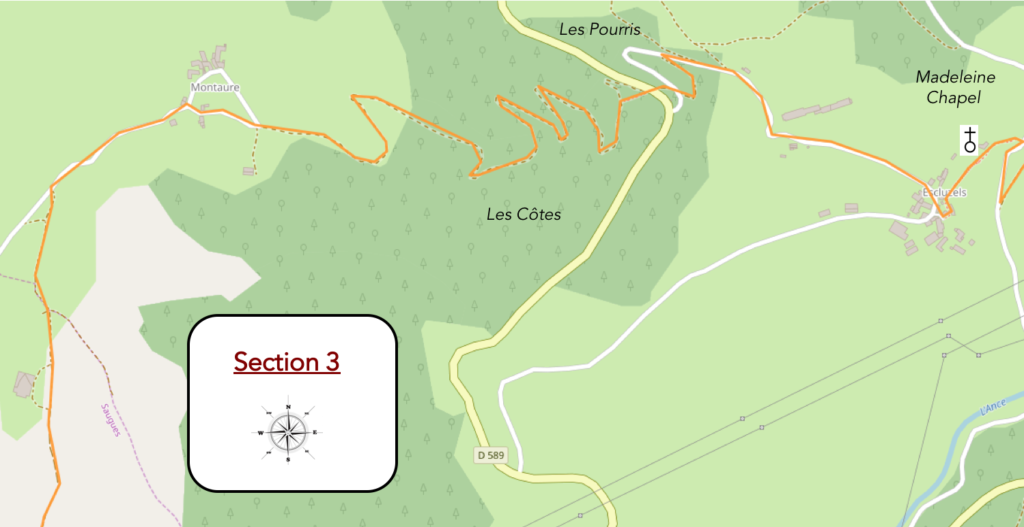

Section 3: A very demanding effort on St James’ track.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: that’s fun, sometimes almost 45%, near Escluzels. You must reach Montaure to catch your breath back.

|

Further up, the pathway is a pretty gymkhana on angular stones, in the lush vegetation, almost touching the scree of the volcanic cliff.

|

|

|

|

Shortly after, the pathway changes direction. In front of you, above a barrier, you can catch a fleeting glimpse of the first houses of Escluzels, well above the trees.

|

|

|

| Beyond the barrier, the slope is quiet for a moment and the pathway joins the small paved road that you followed from the village. You are never far from the cliff. |

|

|

| The slope is then again tough on the paved road, under the oaks, the spruces and the shoots of beech and chestnut, until finding an iron cross planted on the bank. |

|

|

| From here the view is still open on Monistrol d’Allier. Above, you can now see Escluzels, which seems a gunshot away. But you have not arrived there yet. |

|

|

| Still a small barrier, when the GR65 leaves the paved road to a wide dirt road heading to the Chapel of Madeleine above. It is from the barrier that the slope becomes seriously severe. The slopes will soon be around 30 to 40%! |

|

|

Then it gets complicated … …

Wait for the video to load.

| The cave Chapel of La Madeleine stands, close to the dirty road. A chapel dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene is mentioned in an ancient text dated 1312. Was there a Celtic dwelling in this rock fault? In the 17th century, a pediment was built to close the hole and turn it into a chapel, which quickly gained notoriety. Basalt columns dominate the troglodyte chapel. Placed here on the way of the pilgrim, it is a welcome stop after a really tough climb. |

|

|

| Beyond the chapel, it’s hard to imagine a track steeper than that one leading to Escluzels hamlet. More than 40% slope, on stairs carved into the basaltic hillside. Obviously, sometimes, sloping up or down, it is according to, can be even more animated, especially if you have a donkey with you. |

|

|

Happiness of course…

Wait for the video to load.

| Escluzels has remarkable houses made of all tones of volcanic stones. Like an eagle’s nest, the hamlet rolls proudly on the rocky outcrop. One wonders how it miraculously hangs over the void. |

|

|

| The GR65 crosses the village and steeply climbs on a paved road, above the village, in orchards and walnut trees. Beyond Escluzels, the climb is not over. Far from it. |

|

|

| The paved road is gradually approaching the forest, and you’ll find again the big ash trees along the road. |

|

|

| At a place known as Varennes, about ten kilometers to Saugues, the GR65 leaves the paved road for a wide dirt road. Coniferous trees, especially pines, show up. |

|

|

| After a big hairpin in the woods and a crossing again with the small paved road, the pathway reaches the D589 departmental road, which has a course almost as tortuous as the GR65 to arrive at Saugues. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway then passes on the other side of the paved road. Then start the pins in the forest. It takes almost one kilometer to reach Montaure. |

|

|

| The slope is tough here, sometimes well above 15%, but the forest is beautiful. The pines are straight like asparagus or crooked like serpents, extending their arms to catch some light. Spruce trees and very rare white firs hide out. But, it’s a mixed forest. The ash trees are still present in droves, the maples are rare, but they compete in height with the venerable beech trees, which make room for themselves. |

|

|

| The track will make many zigzags in the forest, sometimes coming out in rare clearings where the ferns express themselves, almost as high as small trees. |

|

|

| This region of Haut-Allier is neither brutal nor heroic. This is not severe mountain. Sometimes light does not penetrate the forest. The pathway is hidden under the big trees. This is because the spruces have taken power and are huddling against each other. Another family and a donkey. Here, the donkey is less busy, the baby sleeping in father’s child carrier. Donkey renters must be happy to see the summer arriving. |

|

|

| Further afield, the forest opens on the hillside where a few meadow pastures and some fields turn green. The clearings announce Montaure. |

|

|

| The slope is steep, sometimes excessive and the foot may lack confidence on steep slopes. The climb must be tough for many walkers, given the number of picnic places and drinking places that will flourish in the hamlets crossed. Signs announce near happiness. The pilgrim in saliva in advance.

A refreshment bar was once present in the hamlet, it is now closed, but other signs already advertise refreshments further along the route. Here, pilgrims often mop their sweat and take a break, after a climb that some will consider endless. Montaure is a handful of old houses by the road. Here, volcanic stones still make the law, a law which will soon be called into question by the Margeride granite. |

|

|

|

|

| From here, the region is bombed on a wavy geometry, flattened, lowered. And in the midst of this peaceful nature, the farmer grows black wheat, rye. But on this high plateau above 1000 meters, breeding is the reason for people.

Beyond Montaure, the slope is gentle in the middle of lush meadows and farms, sometimes isolated. A paved road slopes up, quiet, since the hamlet. |

|

|

| Without taking too much care, the landscape changes in a few kilometers. The granite of the Margeride successively succeeds the basalt of Devès. Here there are no greyish, steep mountains or dizzying precipices, but vast pastures whose summit is crowned with tall forests. Here beautiful Aubrac cows are waving their eyes made of black. |

|

|

| On these gentle and large hills, which you can climb without difficulty, this is only a fair reward for the previous effort. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a wide dirt road replaces the tar. The eye is lost in an infinitely bucolic and sweet landscape. The clusters of pines and solitary ash trees proudly play parasols, interacting with the light, with the clouds. Here is a large field of rye, the pride of the Margeride, or triticale. This grass, the first cereal created by man, is a hybrid between wheat and rye. This cereal is grown mainly as a grain feed. |

|

|

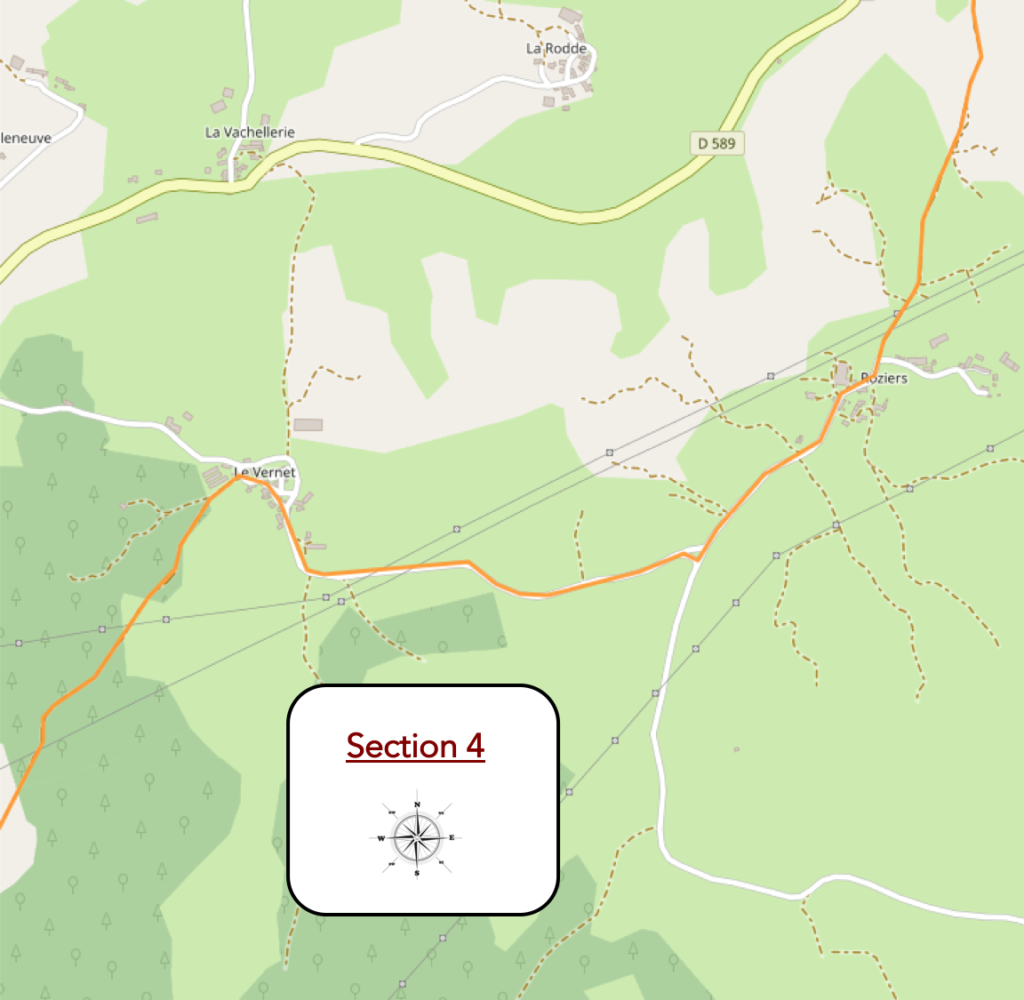

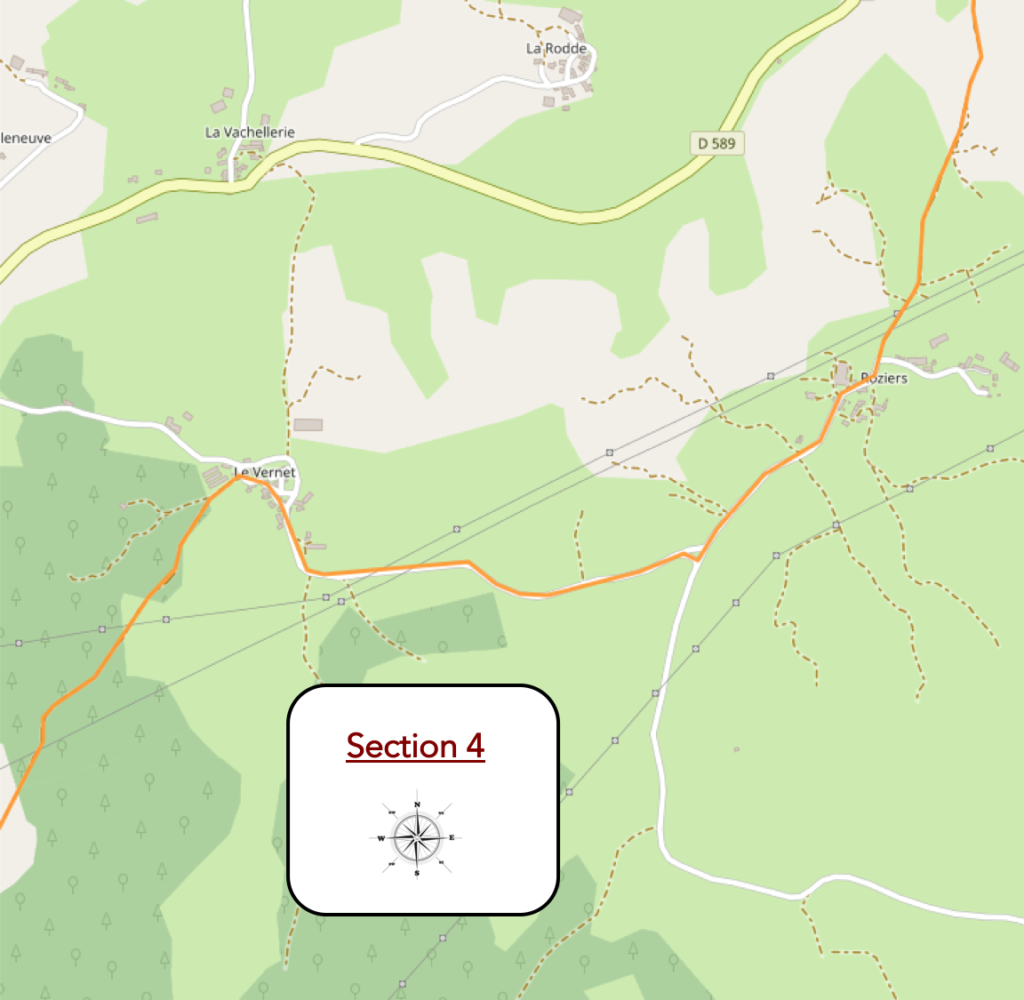

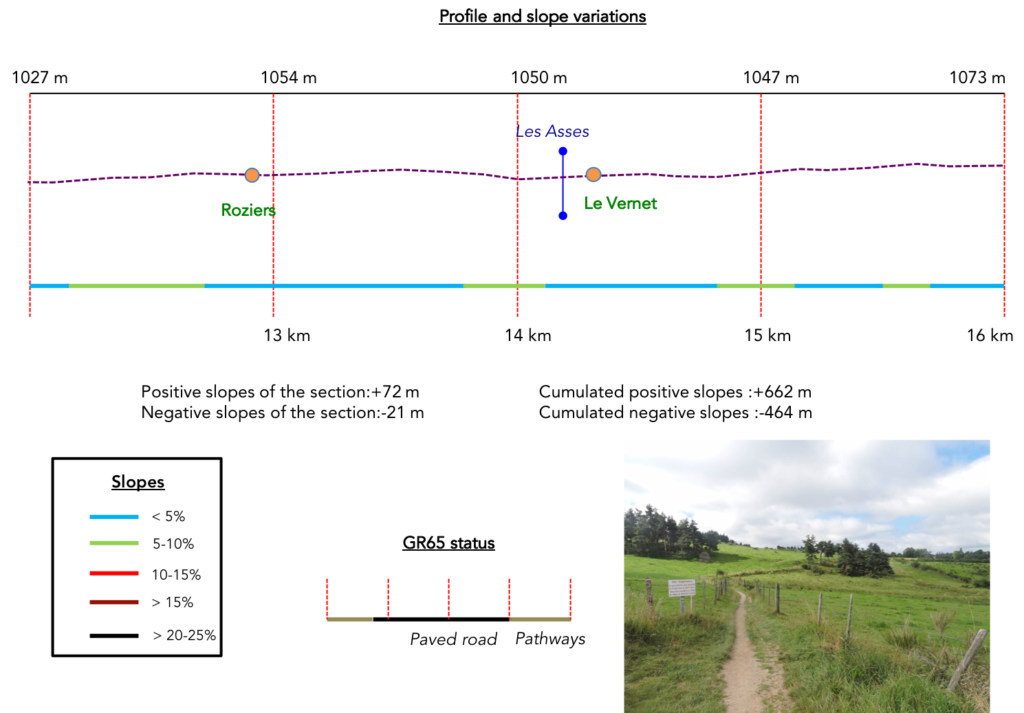

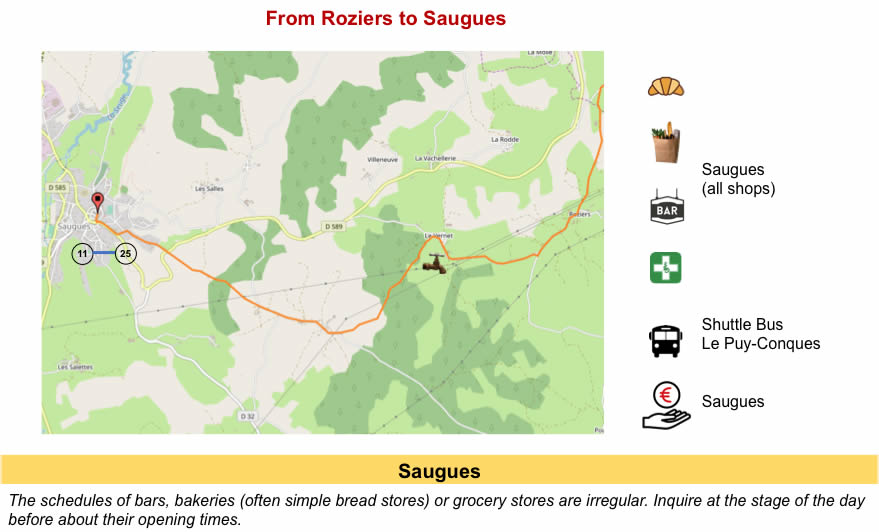

Section 4: Light ups and downs in the pastures.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| What is striking in the day’s stage are the notorious contrasts. You came out of the depths of the gorges carved by the Allier River, rough slopes, to find you now on gentle hills. And yet, it’s the same rough country, with harsh winters. |

|

|

| Sometimes granite boulders run along the route, as if to better mark the nature of the soil here and to signify your arrival in Margeride. The dirt road quickly approaches the hamlet of Roziers. |

|

|

| Further on, the dirt road then gets to Roziers, a few farms quietly ranged at the edge of the road. The water flows cool to the fountain. You can also take a leap to a world of happiness, which offers in addition the chatter to cool drinks. |

|

|

| Beyond Roziers, the GR65 still climbs a bit on the tar. Here,a flock of Montbéliarde cows goes to see if the grass is greener further. The owner tells us that they are good dairy, very robust. Alas, they have a little fragile foot. |

|

|

| The road still climbs a little, gently sloping under the ash trees to the top of the hill, then down the other side. All around, conifers make dark stains. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the paved road gently slopes down towards Vernet, in the middle of pastures and fields of rye. |

|

|

| All around, these are only grasslands, large trees, a relaxing countryside, preserved and welcoming. If you walk here in the spring, it’s green like Ireland, a little less in summer. |

|

|

| The road approaches soon Vernet village. In the meadows, the sheep pause under the maples and ash trees. |

|

|

| These villages are often screwed on the hill in the area. In Vernet, granite replaced volcanic stones. It is the basic material of houses, crosses and fountains. These houses, which stand on the hillside are all a little alike. Pearl gray granite resists the onslaught of time and will continue to do so. The modest altitude of these hamlets does not change anything. In winter, the climate can be harsh and hostile here. |

|

|

| The GR65 crosses and leaves Le Vernet on the heights, where behind the cross on the granite rock nestles a henhouse where the peacock is proud in the middle of hens, pheasants and turkeys. |

|

|

| Here a wide dirt road flattens in the meadows, marked here and there with some maples and ash trees. Further on, stand coniferous forests. It is the charm of the countryside that does good. |

|

|

| The nature here is calm, intact, with its hollow pathways, its grove, with, as a bonus, a kind of high plateau on which goats’ droppings and dung of cows signaling the presence of a peasant life essentially devolved to the breeding. |

|

|

| Further, the lane narrows as Rognac village approaches. The meadows are so sweet, ready to welcome the walker for a nap. |

|

|

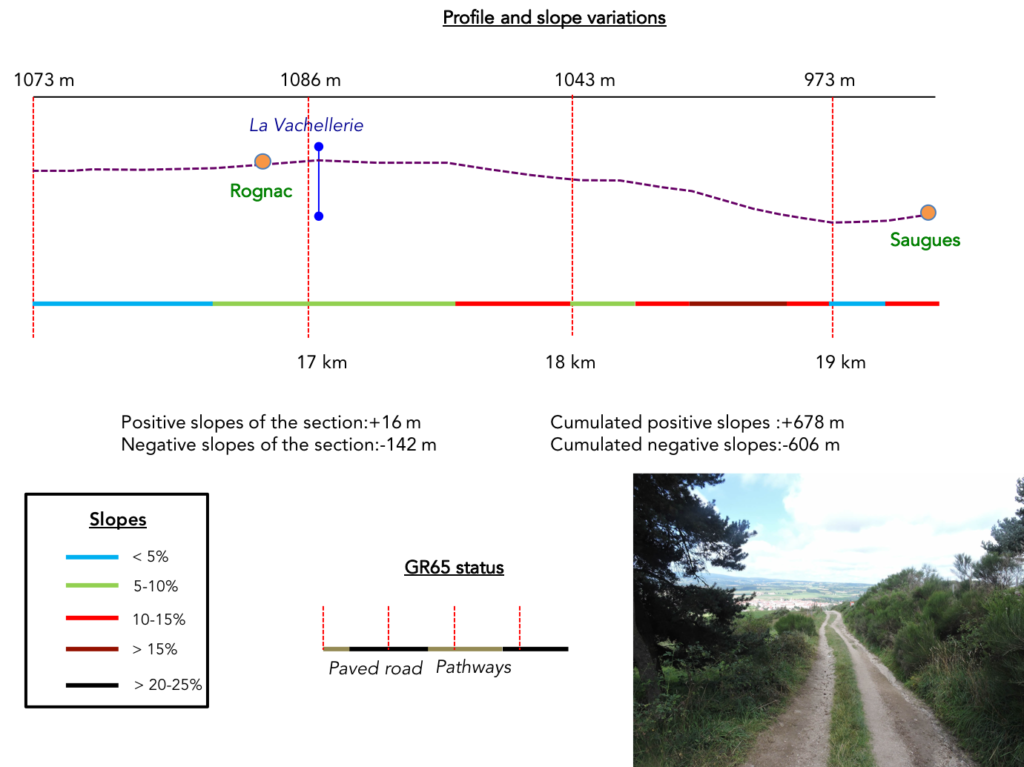

Section 5: Downhill to Saugues.

Overview of the difficulties of the route: without much problem, if not some very steep sections at the approach to Saugues.

| The narrow pathway still runs in the wild nature for a while, under the pines and ash trees … |

|

|

| … before ending up on the tar, under the ash trees, at the entrance of Rognac, at 1100 meters altitude, the highest point of the stage. You are now in Gevaudan, on the edge of the Margeride, a mountain range that rises to 1551 meters at the Signal de Randon. Picking also holds an important place in the region. Mushrooms, blueberries, lichens and daffodils are the hobbies or the toil of the people of Saugues. You will be told that for many of them it is the thirteenth month. The sale of cut mushrooms, ceps in particular, is a tradition of Saugues autumn fairs. Lichen and narcissus are used for the development of perfumes. |

|

|

| Rognac is one of those villages of Gevaudan and Margeride, uniform, magnificent in their sealed granite stones, made to last a long time. The pinnacle is not that of a chapel, but that of the house of assembly of the village. |

|

|

| Beyond Rognac, the GR 65 flattens straight on the tar in the countryside. But quickly, it forks in a small narrow lane that initiates a continuous descent towards Saugues. |

|

|

| Here, let’s go down to Saugues at another time of the year…

The pathway slopes downhill into the pines. The slope is not very tough at the beginning of the descent, and the horizon opens on the broad plain below. |

|

|

| The pathway steadily slopes down on the stones and the dirt before guessing in a near horizon Saugues and its red roofs. If you walk here after spring, you will see the broom in bloom. |

|

|

Coming out of undergrowth, the landscape shows up unusual wooden sculptures, made from single trees, as a sign of the mysteries of the area. The wicked bloodthirsty beast appeared unpredictable, slaughtered whoever else better, devoured children of whom only bloody remains remained. Everything was terror in the country. Even the shuddering bushes in the wind or the crackling of branches in the undergrowth announced the tragedy.

| These strange monsters, cut from a single tree, mark both the austerity and the mystery of the region. |

|

|

| The “Gevaudan monster” himself keeps an eye open for the pilgrim, when the pathway joins the D580 departmental road. the GR65 crosses the road and slopes steeply down towards the small town. |

|

|

Saugues, with its 2’000 inhabitants, is famous for its “Beast of Gevaudan” for its mushrooms and wooden clogs. Saugues is also an important livestock market. The cattle market takes place on Mondays and the sheep market on Fridays. Here, more than 100,000 head of cattle are treated each year.

Before the arrival of the Romans, the country was inhabited by the Gabales, a proud and fierce people who lived in thick forests, which covered almost entirely the region. Julius Caesar called the country Salgacum. With the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the country passed under the domination of the Franks. From 725 to 730, the Saracens and the Moors burned almost everything in their path. In the 12th century, Saugues became under the control of the Mercœur, a dynasty also present in St Privat d’Allier, one of the most powerful families in Auvergne. Most of the fortifications and the Tower of the English date from this time. At that time, the country included 507 parishes and 5665 families, disregarding the poor. Then, between 1337 and 1453 came the terrible “Hundred Years War” between France and England for the control of the throne of France. In 1380, Charles V sent troops to take control of the so-called “English” who held the siege of the city. In fact, these people were not English at all, because after the treaty of Peace de Bretigny of 1362, many mercenaries were unemployed and began to ransack the towns and abbeys of the country. They were called “routiers” or “anglais”. That’s why the tower here is called “Tour des Anglais” (Tower of the English). The end of the war brought a climate of insecurity, and the fortresses and castles were repaired everywhere. In the 14th century there were 30 fortified castles in the area. In 1788 came the tragedy. The communal oven caught fire. In a few hours, the fire destroyed almost the whole city, the castles, the prisons, the churches and the hospital. No streets were spared. More than 100 houses were burned to the ground. The fire had taken everything. The tower of the English was the only tower of the castle to remain intact. The inhabitants rebuilt the city with the stones of the castle. Today, the tower that stands in the centre of the city is the local clock.

|

The Collegiate Church of St Médard retains its original octagonal tower dating back from the 13th century. The church was partially destroyed in the 16th century, then gradually amended. It contains the relics of Brother Benilde, a beatified local saint, then recently canonized. |

|

| The Brotherhood of Les Pénitents (Penitents) was founded in Saugues in 1652. The brotherhood is part of confraternities of Catholic essence, with statutes that recommend penitential exercises, such as fasting, assistance to the deceased and the sick. They are classified according to the habit that the penitents wear during processions or their penance work. Here in Saugues, the dress is white. In the nineteenth century, the community numbered 200 people. Today it remains 40. The procession of Holy Thursday with hooded penitents is an exceptional event. The Chapel of the Penitents (which can be visited on request) was erected in 1681. It burned in 1788, and was restored later.

Lucien Gires (1937-2002), a local artist, was the artistic anchor of the city. He was responsible for the restoration of the Tour des Anglais, the illustration of the life of St. Benilde, but also for the development of the museum of the “Beast of Gevaudan”. The museum was inaugurated in 1989. The museum retraces the mysteries around the terrible mythical beast that killed more than 100 people in the region (for details, see the following step: From Saugues to Le Sauvage). |

|

|

Local gastronomy

At the end of the meal, you will often be served a “coupétade”, a dessert from central France. The name comes from coupet, a pottery in which the dish is traditionally prepared. It is a variant of the French toast. They start with a bread rich in butter, usually brioche, which is caramelized with butter. Egg and milk are added and cooked as a pudding, after adding fruit (plums, apricots, grapes, cherries, apples).

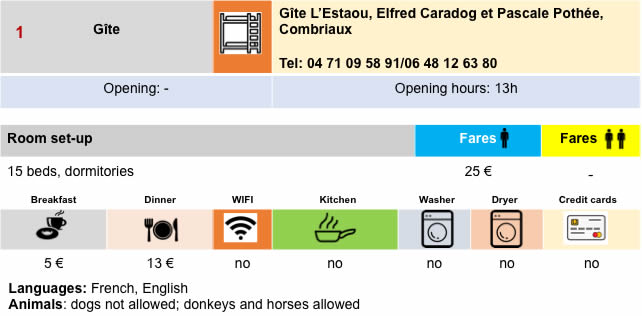

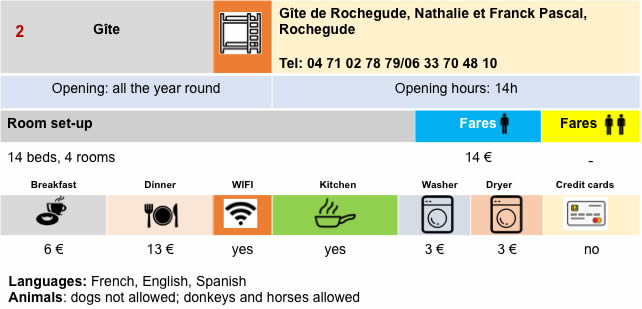

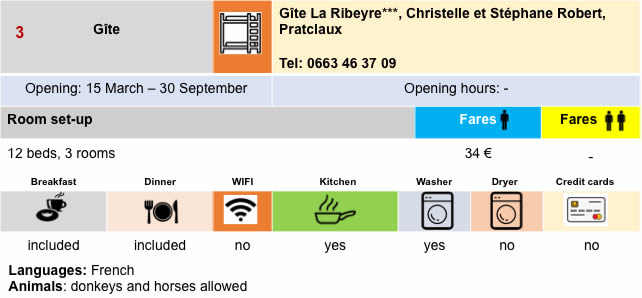

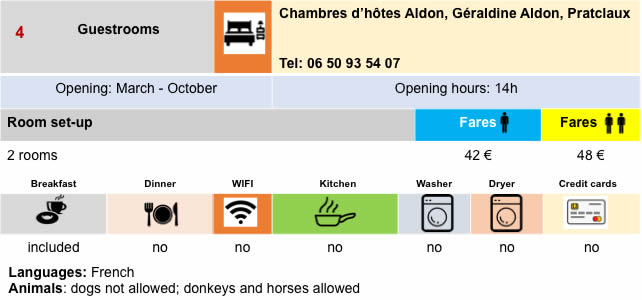

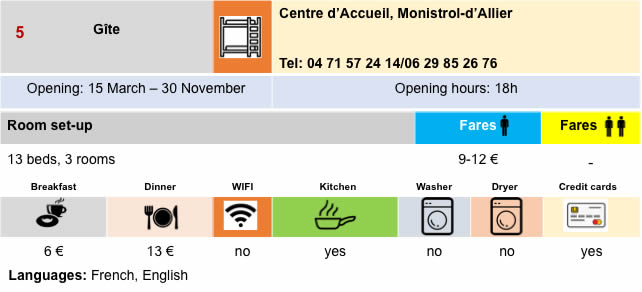

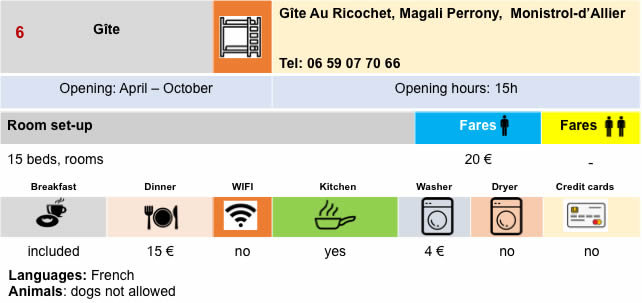

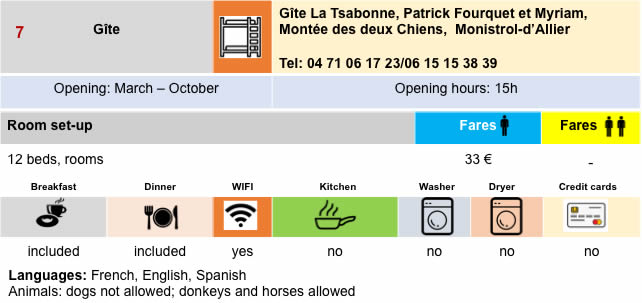

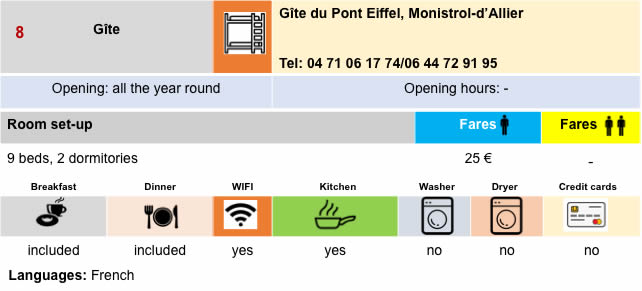

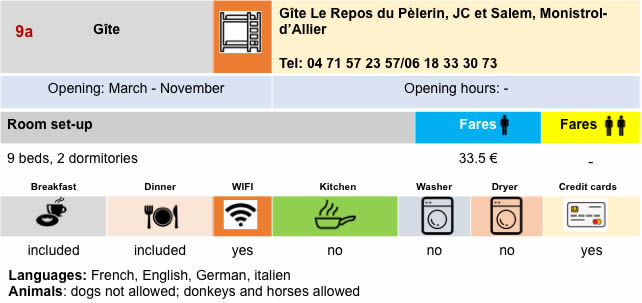

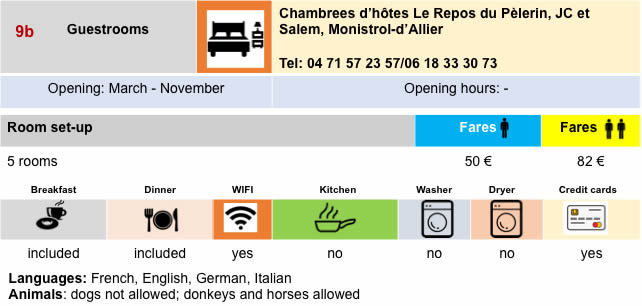

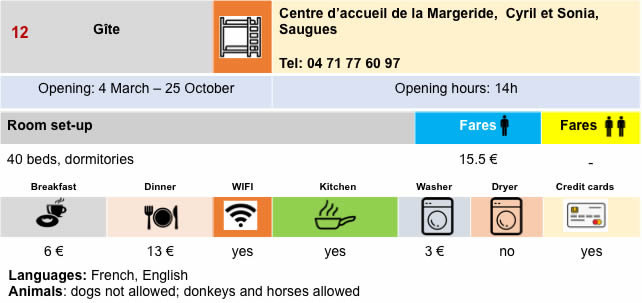

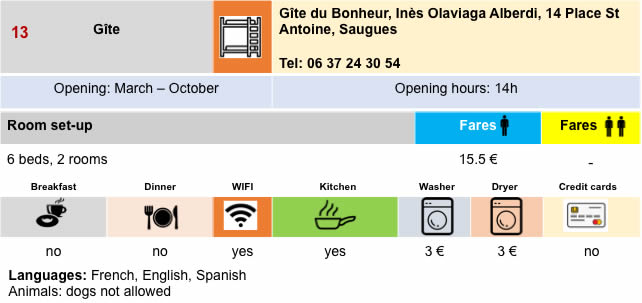

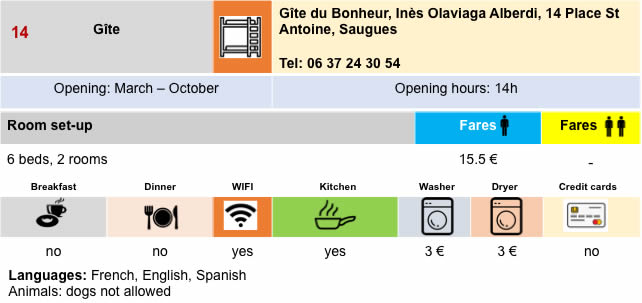

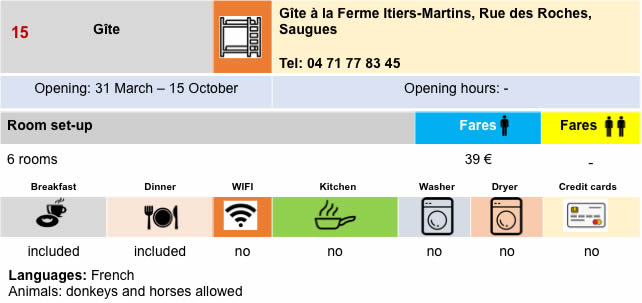

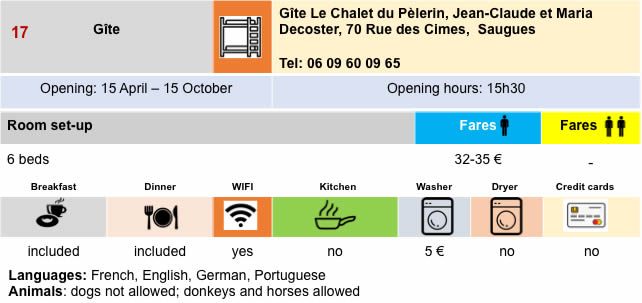

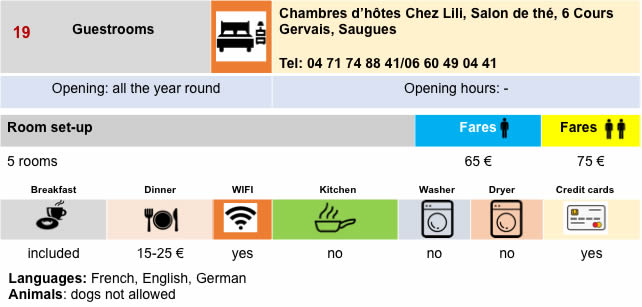

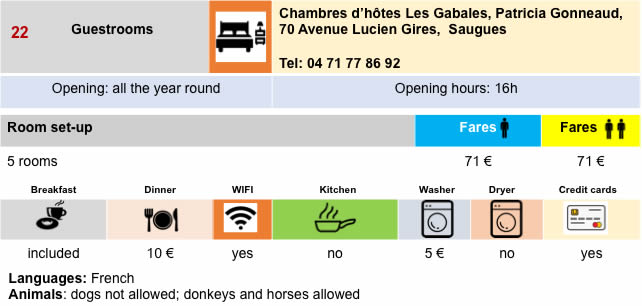

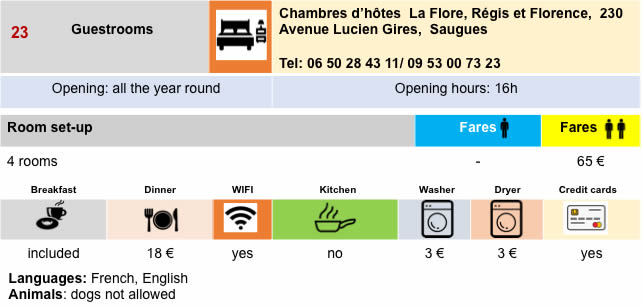

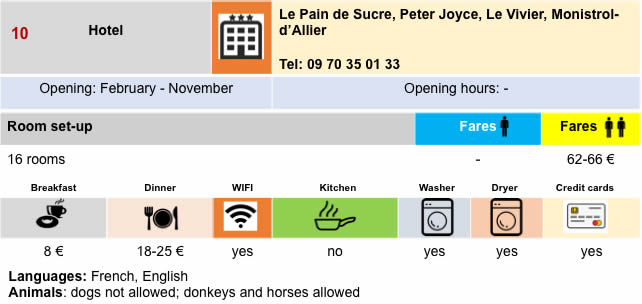

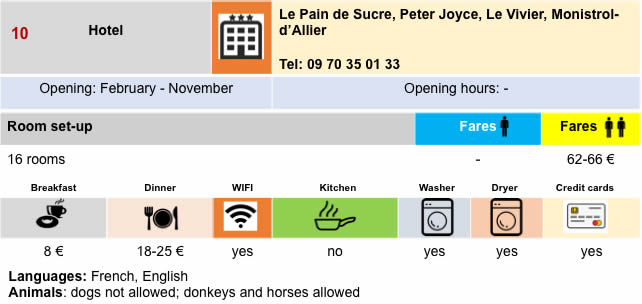

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

|

|

Next stage : Stage 3: From Saugues to Le Sauvage |

|

|

Back to menu |