The splendor of Cami Ferrat

DIDIER HEUMANN, MILENA DALLA PIAZZA, ANDREAS PAPASAVVAS

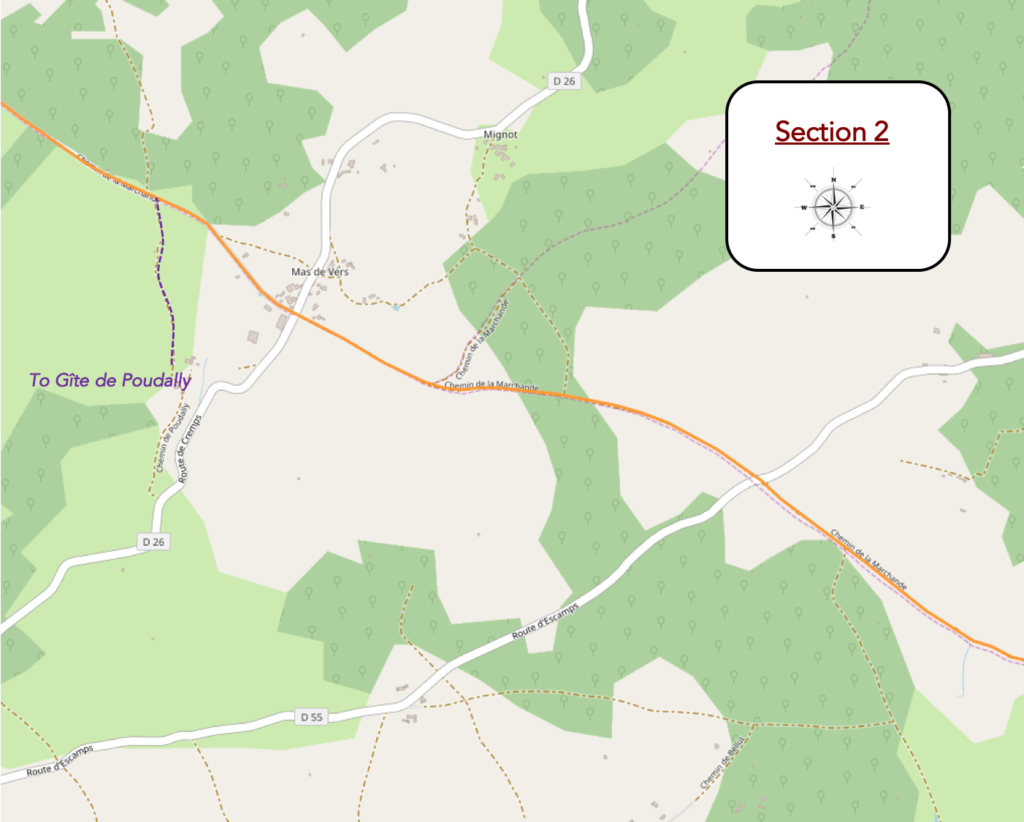

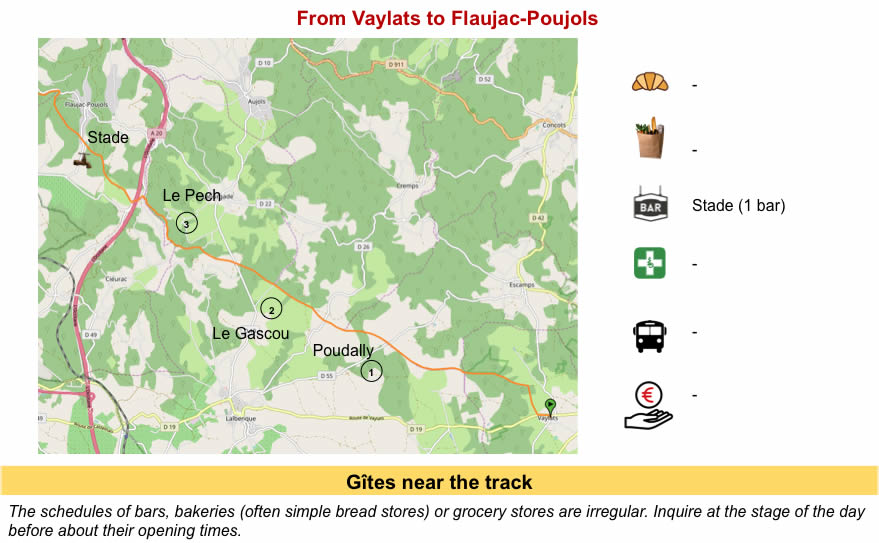

We divided the course into several sections to make it easier to see. For each section, the maps show the course, the slopes found on the course, and the state of the roads. The courses were drawn on the “Wikilocs” platform. Today, it is no longer necessary to walk around with detailed maps in your pocket or bag. If you have a mobile phone or tablet, you can easily follow routes live.

For this stage, here is the link:

https://fr.wikiloc.com/itineraires-outdoor/de-vaylats-a-cahors-par-le-gr65-30297634

It is obviously not the case for all pilgrims to be comfortable with reading GPS and routes on a laptop, and there are still many places in France without an Internet connection. Therefore, you can find a book on Amazon that deals with this course. Click on the book title to open Amazon.

If you only want to consult lodging of the stage, go directly to the bottom of the page.

The whole network constituting the ways of Saint-Jacques in France is recognized by the world heritage. The decision to inscribe the Santiago de Compostela routes in France on the heritage list dates from 1998. By this inscription, UNESCO wishes to draw attention to the exceptional universal value of this heritage. To do this, monuments or trail sections have been selected.

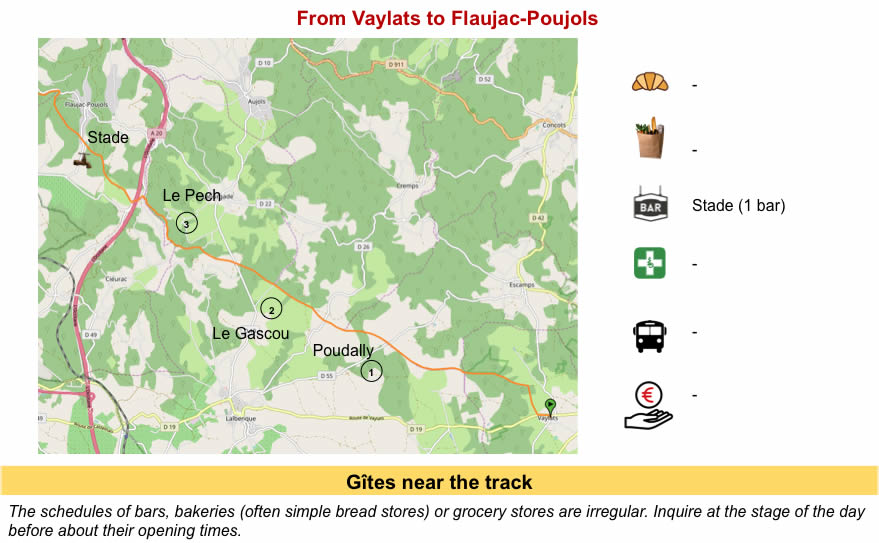

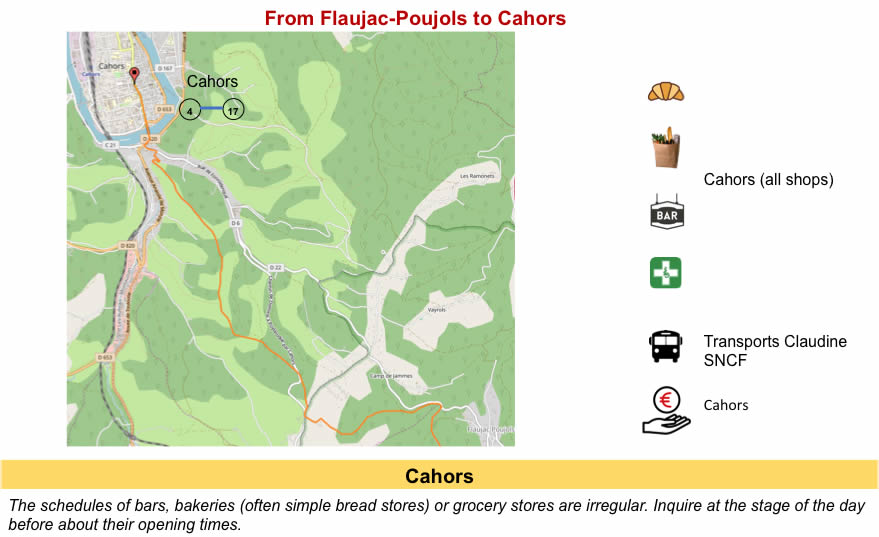

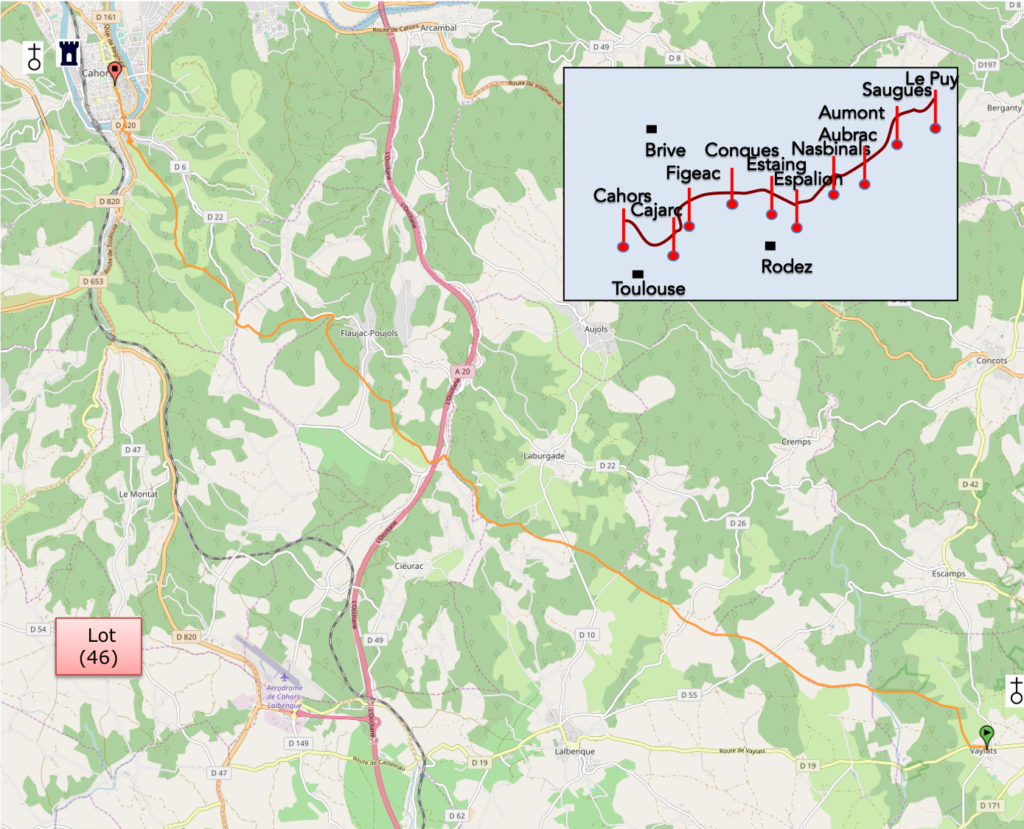

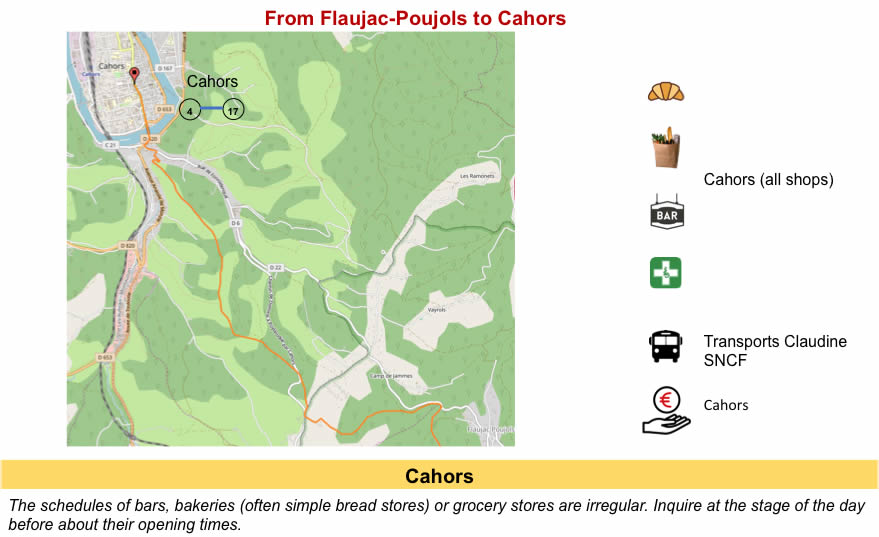

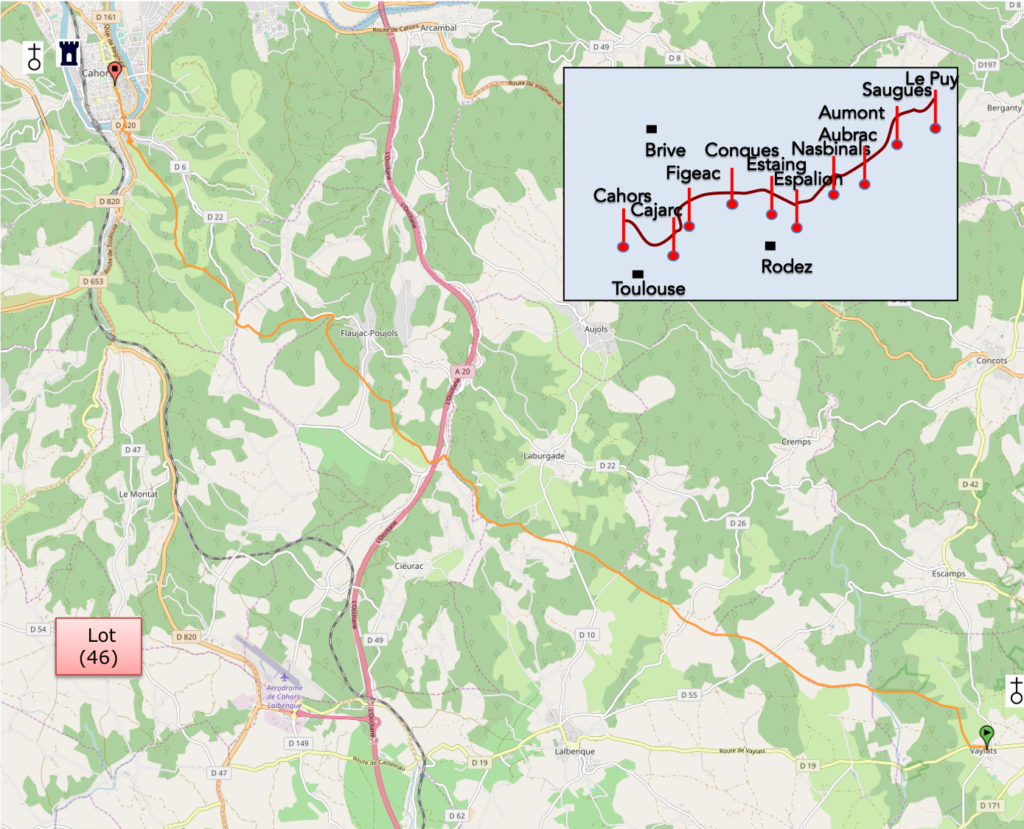

The track approaches Cahors, the largest town on Via Podiensis, with its 22,000 inhabitants. The journey from Bach to Cahors, the 26 km of the Cami Ferrat are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The same is true of St Etienne cathedral and Valentré Bridge in Cahors. The track runs up towards the North and the Lot plain. The route crosses an area where there are virtually no villages. The A20 motorway, Occitan Highway, from Limoges to Toulouse, passes through here. You are still in the Department of Lot. In Cahors, you will be almost halfway between Puy-en-Velay and St Jean-Pied-de Port. This route avoids places of human settlement, which adds to the mystery of this gently hilly part of the causse. The route crosses an area where there are virtually no villages. The A20 motorway, Occitan Highway, from Limoges to Toulouse, passes through here. You are still in the Department of Lot. In Cahors, you will be almost halfway between Puy-en-Velay and St Jean-Pied-de Port. This route avoids places of human settlement, which adds to the mystery of this gently hilly part of the causse.

For the Romans, the way was the Via, a solid, reliable, usually straight way for the passage of carts, soldiers and horses. These tracks were often “railroad” (lou cami ferrât, in Occitan, as hard as iron), in other words reinforced with a packed and rammed coating, most often stoned. When it comes to Roman roads, the word that comes up most often is “it’s straight ahead”. When Julius Caesar invaded Gaules country, he had these roads established to move his troops rapidly throughout the territory. In medieval times, Cami Ferrat from here was an important pilgrimage route that linked Rocamadour to the South of France, and beyond, Rome and the Holy Land.

Cami Ferrat is above all a wide dirt road with little stones, but it sometimes changes structure on the way, especially when the oaks are a little denser than at the edge of the forest and the stones take over the dirt.

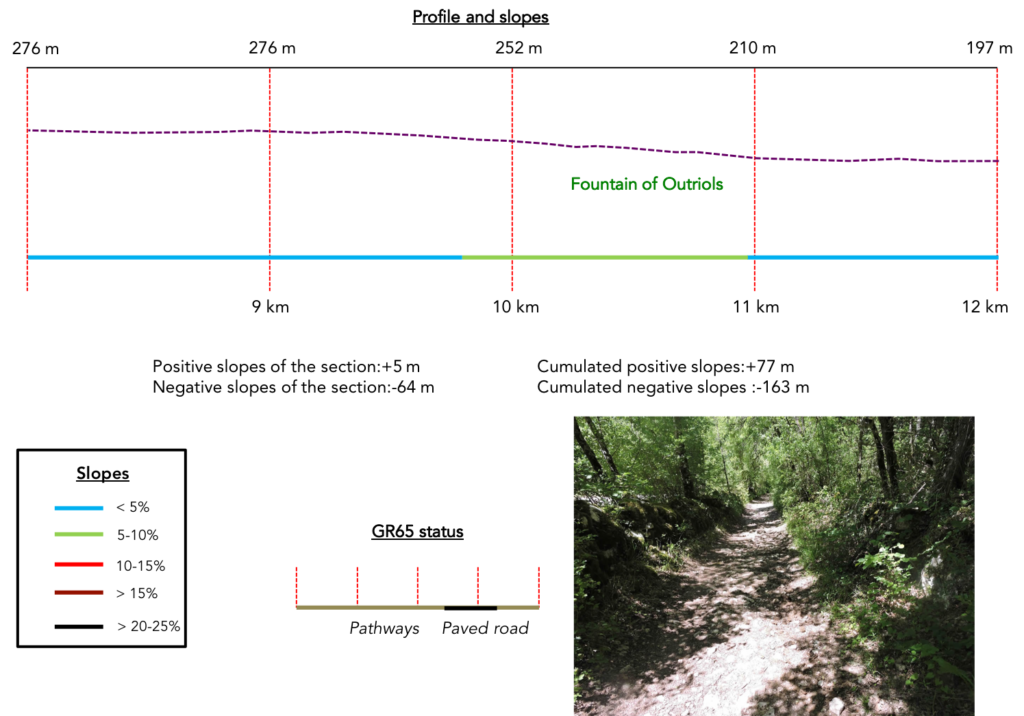

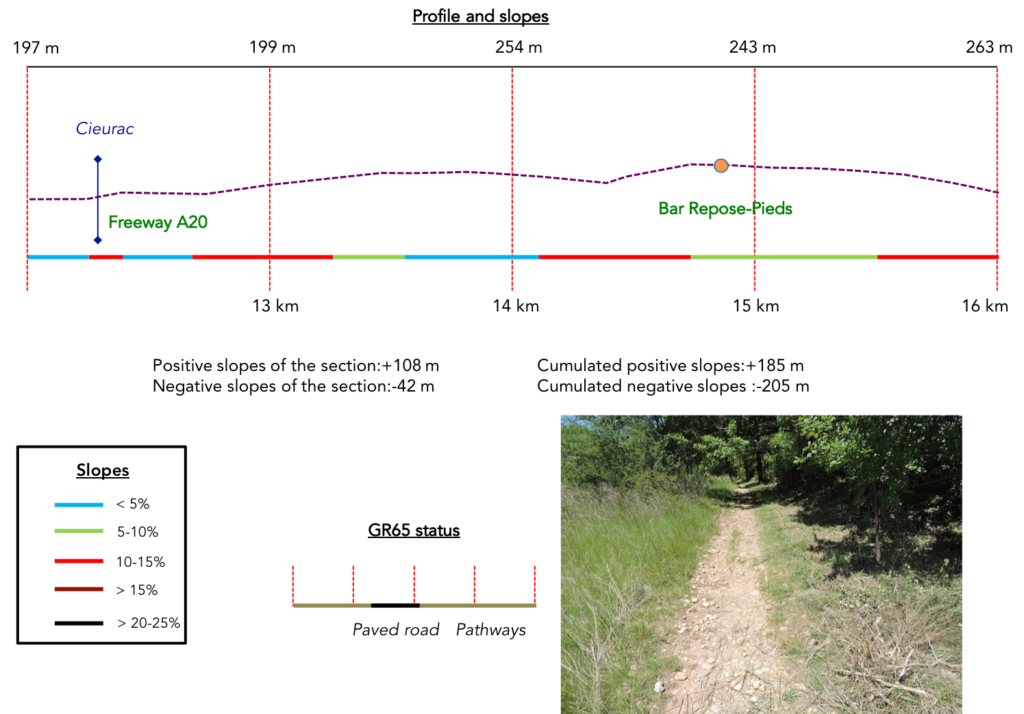

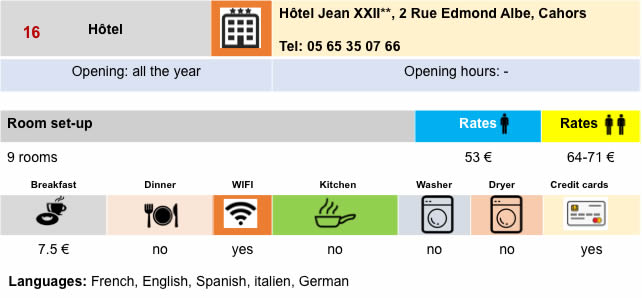

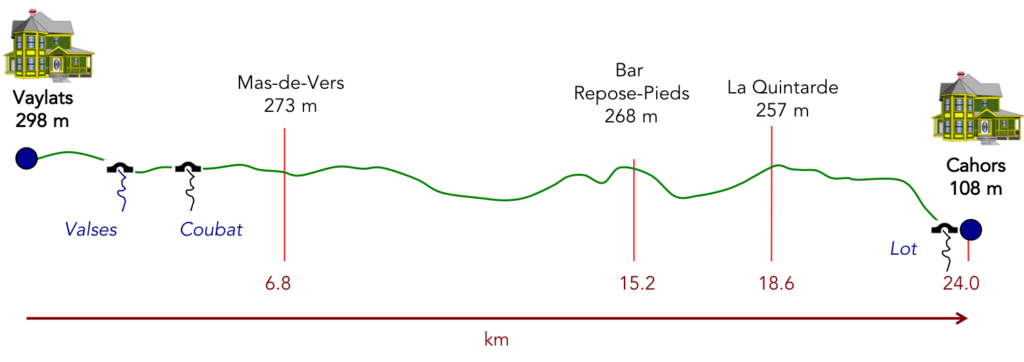

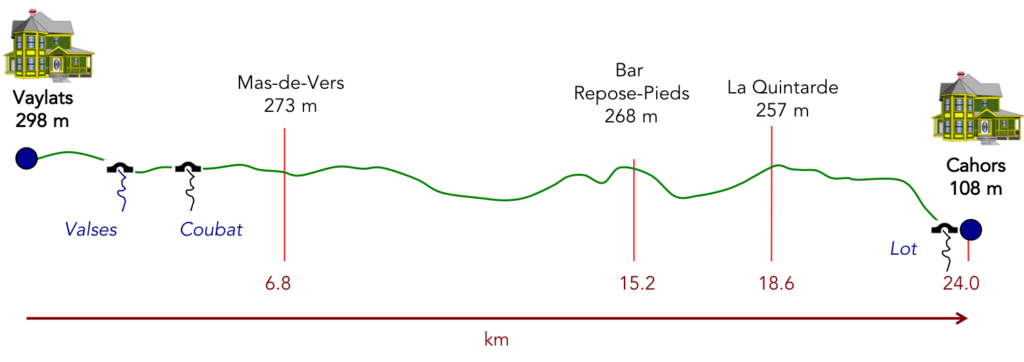

Difficulty of the course: Slope variations (+314 meters /-470 meters) are low. The profile of the stage is now to the advantage of the walker. There aren’t any big bumps, except one halfway through. Otherwise, the track undulates gently. Only a severe and tough descent to Cahors marks the end of the stage.

The Cami Ferrat is above all about wide dirt roads. Little tar, the dream, right?:

The Cami Ferrat is above all about wide dirt roads. Little tar, the dream, right?:

- Paved roads: 5.1 km

- Dirt roads: 18.9 km

Sometimes, for reasons of logistics or housing possibilities, these stages mix routes operated on different days, having passed several times on Via Podiensis. From then on, the skies, the rain, or the seasons can vary. But, generally this is not the case, and in fact this does not change the description of the course.

It is very difficult to specify with certainty the incline of the slopes, whatever the system you use.

For “real slopes”, reread the mileage manual on the home page.

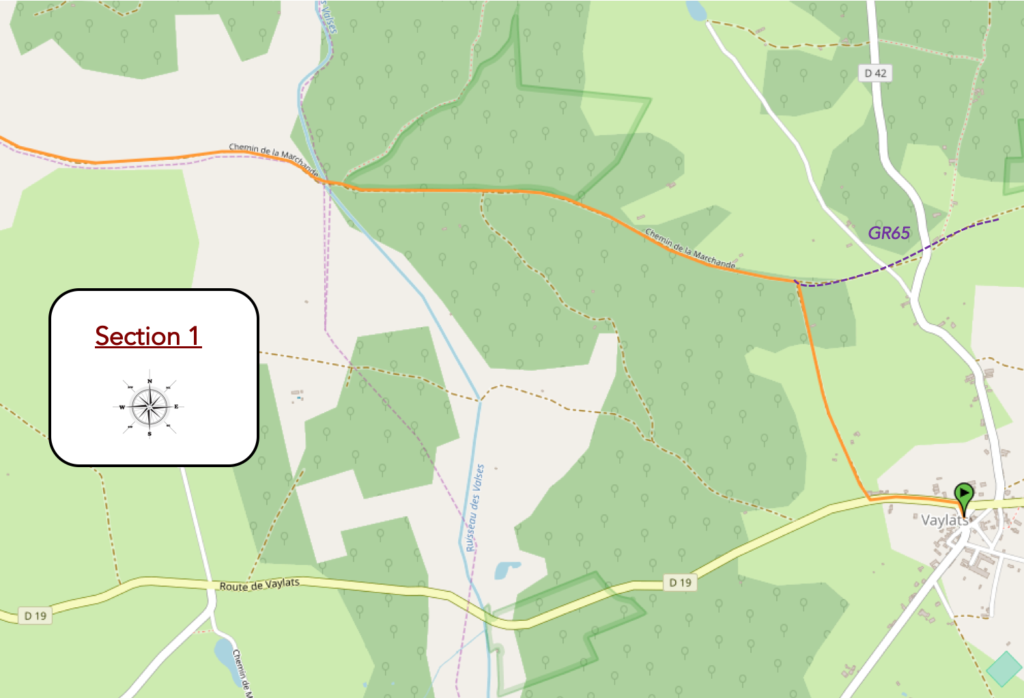

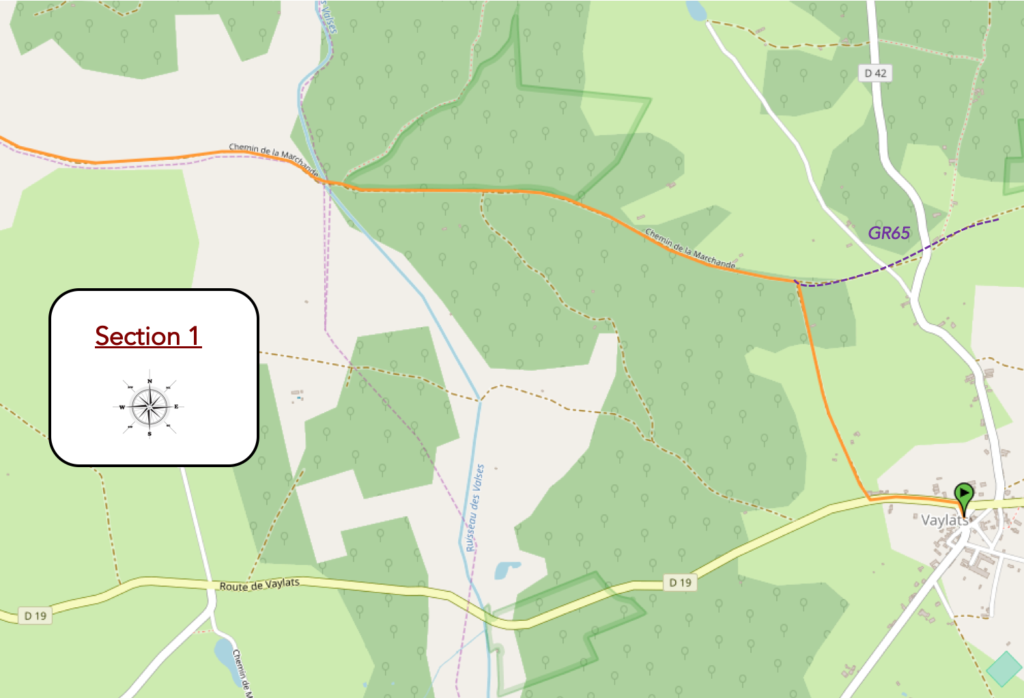

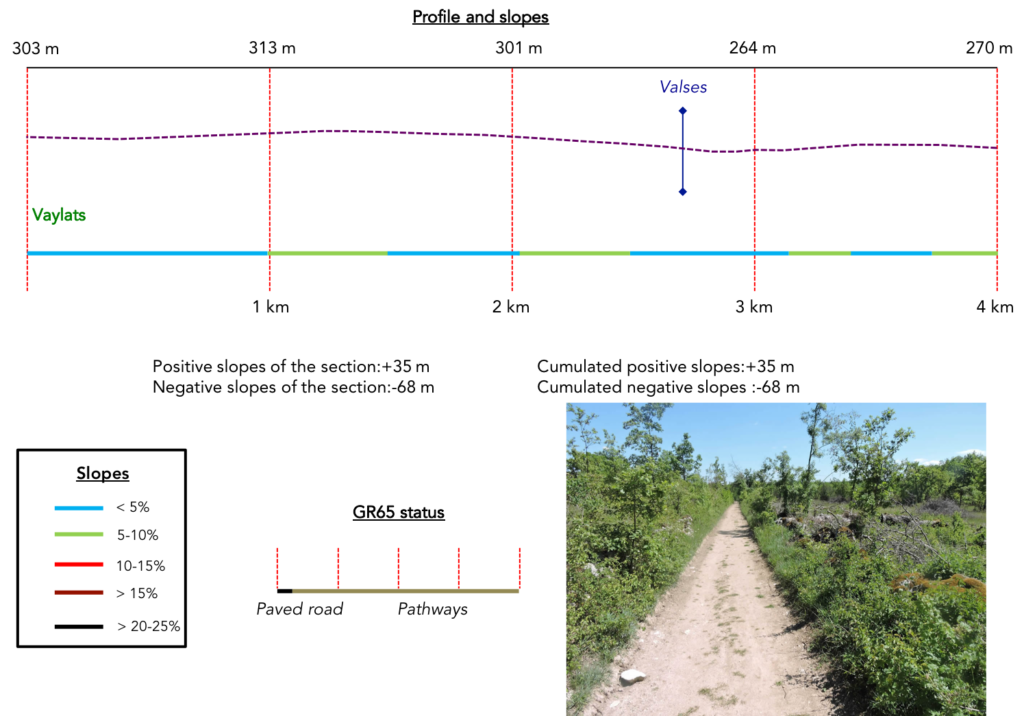

Section 1: Beyond Vaylats, you join the GR65 in the forest.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| As breakfast is scheduled for 7 a.m. at the sisters’ convent, it is often early in the morning that the pilgrims leave the convent. |

|

|

| You have to join the GR65 further in the forest. The route first begins on the road that leaves the village. |

|

|

| Shortly after, you’ll find the junction which allows you to reach the Bascot yurts, a new accommodation on the route. But it is also here that the route leaves the road for the forest. |

|

|

| You then quickly find yourself in the forest on a wide dirt road with very little pebbles, sometimes with a stone ruin on the side of the track. |

|

|

| The road is almost straight in the shade of the large oak trees. |

|

|

| At the end of the straight line, the route joins the GR65. Cahors is 24 km from here, and the first point of civilization is at Mas de Vers, about 5 km away. |

|

|

| Here you do not meet anyone, except the pilgrims carrying their heavy bags, although it must be said, many pilgrims, who over time have become hikers, travel with a light bag, the excess being carried by transport companies. |

|

|

| The pathway sometimes runs along stone walls or in clearings. The oaks huddle together, bend down to the ground, act as guards of honor for the walker passing by. Oaks grow and choke out other trees and small shrubs by depriving them of light. You will rarely see pine trees, which need light to develop. Sometimes a few rare brooms quiver. |

|

|

| There are few signs of a human presence. Only a few stone monuments from the past mark the landscape. |

|

|

| Two donkeys start braying in the deep forest. Closer, at the edge of the forest, two masked equines watch you pass, indifferent. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway changes register. It comes out of the woods. From a straight line, it begins a bend, begins to descend and stones appear on the ground. What marks the causses are the stones at the edge of the pathways, sometimes gray, sometimes yellow and ocher, on which a very particular light plays, in a country where sunken pathways alternate with arid moors where junipers and boxwoods reign. Dogwoods, Montpellier maples, and small downy oaks, in abundance. |

|

|

| The sun is rising today, which will only enhance an extraordinary landscape. |

|

|

A “caselle” here only has the objective of being prey to photographers.

| At the bottom of the slight descent, the pathway crosses the Valses stream. In dry weather, you will never see the slightest drop of water here. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the pathway climbs gently uphill along incredible stone walls, the true jewels of the causses. Here again, as between Faycelles and Cajarc, UNESCO took pleasure in classifying lost tracks, far from men. |

|

|

| Sometimes a cyclist passes. |

|

|

To see crops, you have to widen your eyes. In these funnels of greenery, the forest can sometimes give way to a sort of scrubland, or to plantations of truffle oaks, of which you can guess the potential presence of mushrooms from the round trace of earth which emerges around the trees. We know that truffles grow in poor soils, in limestone and filtering soils. You need a soil in which organic matter decomposes quickly. Truffle mycelium lives in association with the roots of truffle trees, downy oaks or hazelnut trees. But be careful, not all of these trees are truffle trees! Don’t think that all truffles come naturally. Truffle farms are real work. Farmers clear the bushes and plow the land favorable to truffles. During the winter, young oak trees carrying truffle mycelium are then planted. You have to wait 3 to 6 years of maintenance of these trees to hope to see the “burnt”, this grassless zone around the tree, synonymous with great hopes.

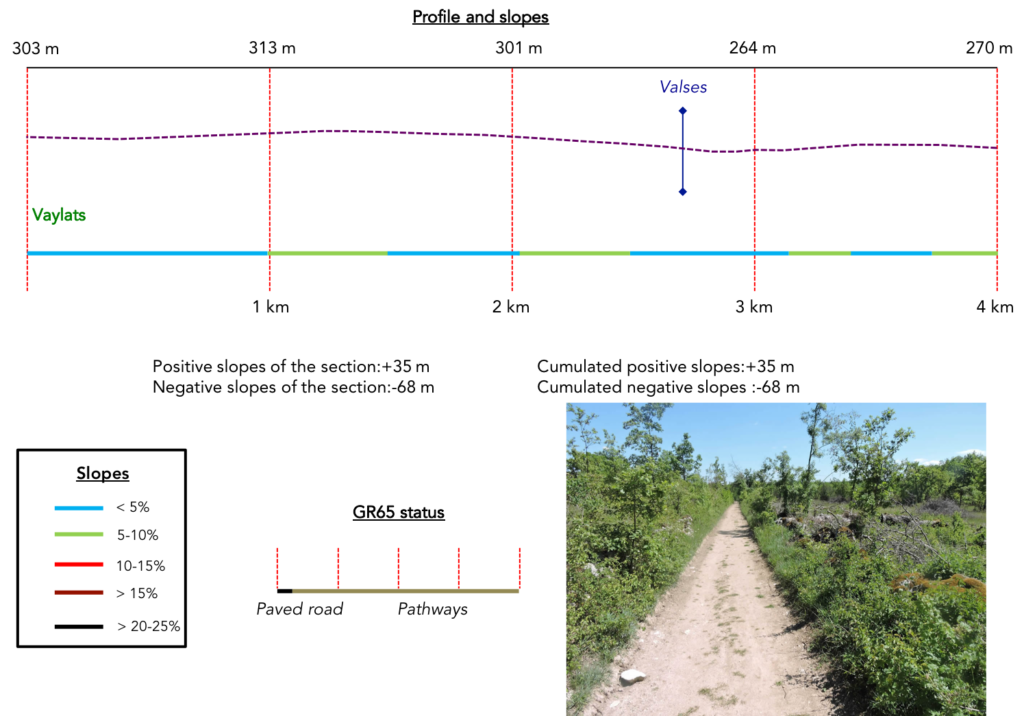

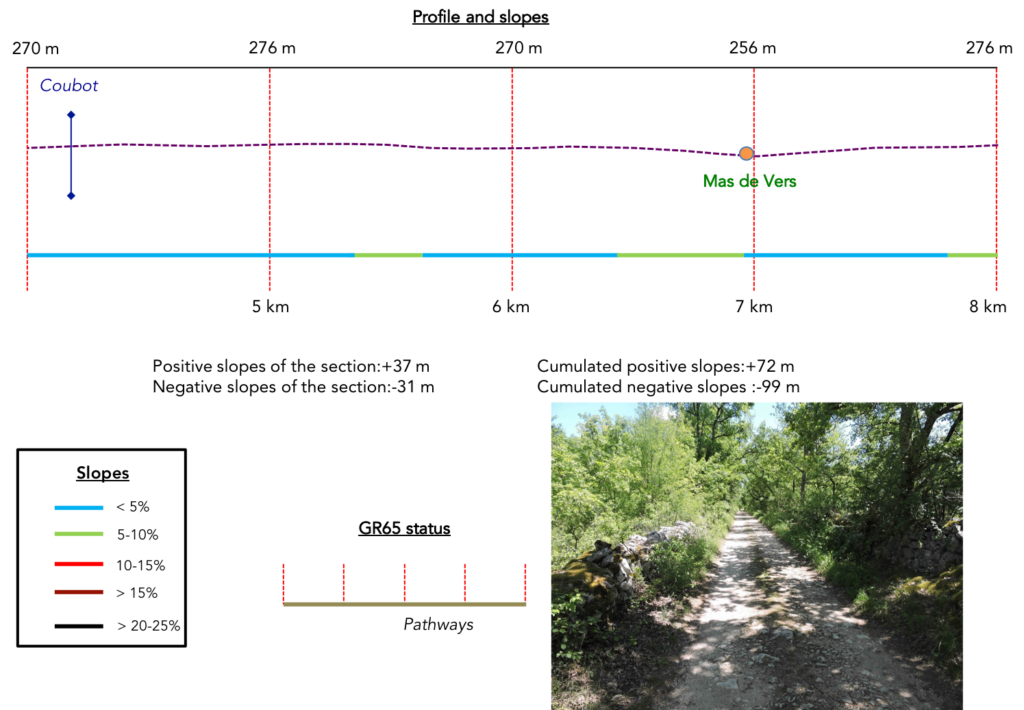

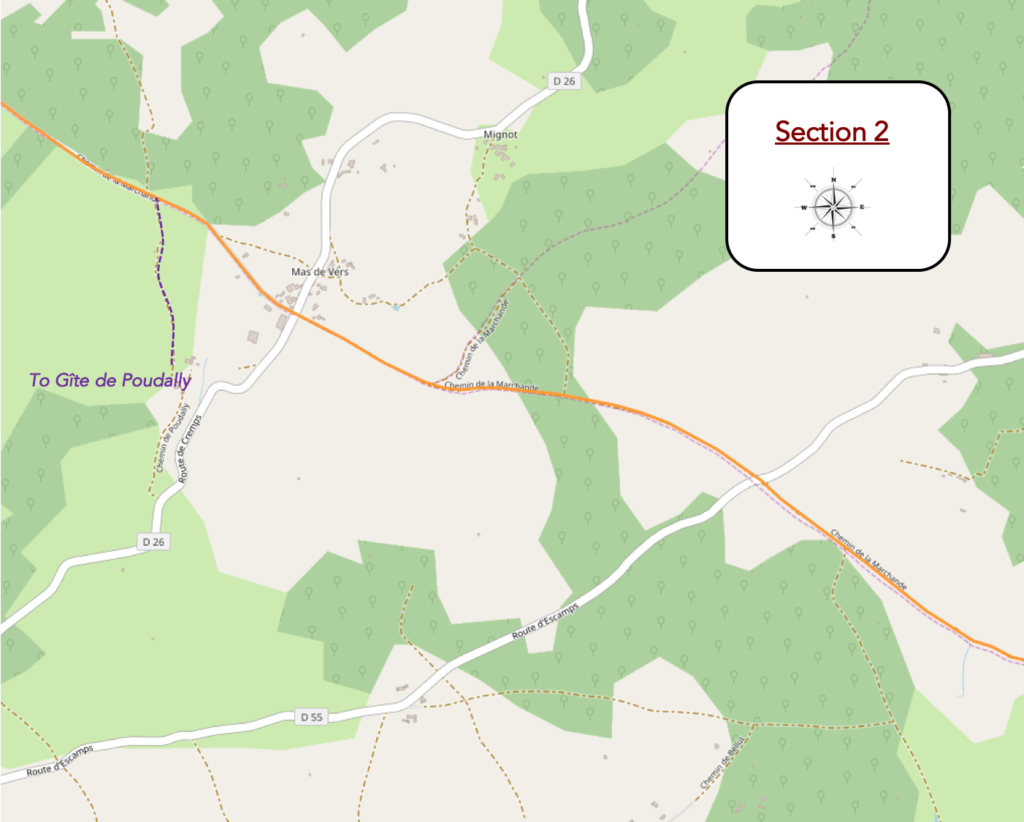

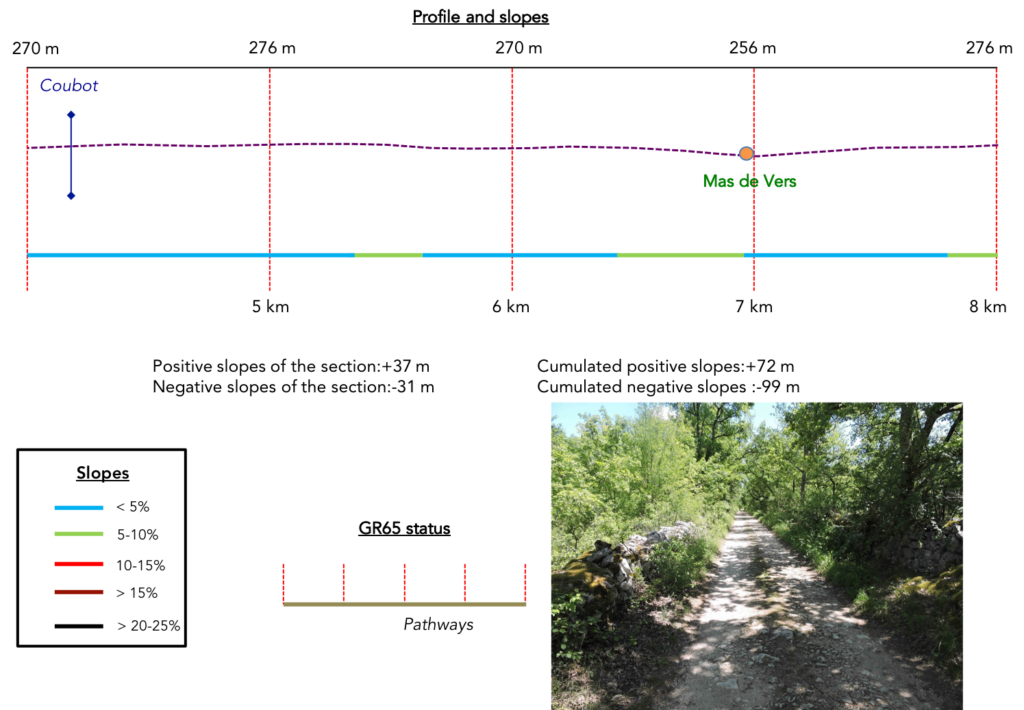

Section 2: Passing through Mas de Vers, a rare hamlet on the route.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

Further up, the pathway reaches a plateau. Nothing grows here on this arid land, dotted with large granite stones.

| And the pathway begins to wander through the steppe. Oak trees, if they have space, grow a little taller. |

|

|

| The pathway remains stony in this symphony of small walls and small oaks which wink at you. What more can be said? Nothing, listen to the silence. It’s just grandiose, timeless. |

|

|

| In the past, boxwoods were the most invasive shrubs on the causses. Almost eternal, they retained their green and orange foliage all year round. Alas, they have disappeared, undoubtedly crushed by the spirals. Junipers have also become rarer. But nature has a horror of a vacuum. And it is the dogwoods who have now taken power. For how long, no one can predict. |

|

|

| On this incredible track designed by the Romans, you will sometimes feel lost, almost alone in the middle of wild nature. Because on all French routes, the cohort of pilgrims dilutes over the kilometers, which is not the case in Spain. |

|

|

| Further on, the stones disappear from the pathway, which has become as wide as possible. |

|

|

| Then you’ll see the first houses of Mas de Vers appear. |

|

|

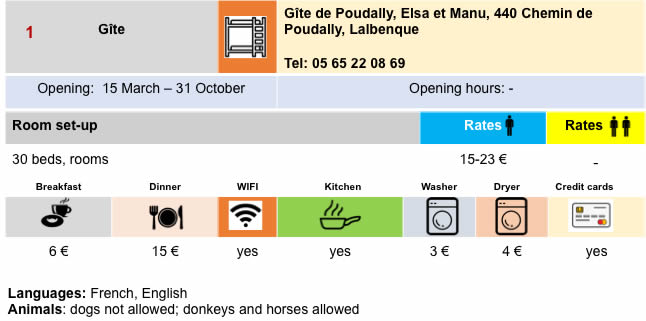

| At the entrance to the village, a shortcut leads to a gîte, the Poudally gîte, which should be noted, as there is a lack of accommodation before Cahors. Has UNESCO struck again for the misfortune of landlords? it must also be said. One more kilometer sometimes discourages the pilgrim. |

|

|

| The GR65 leaves the hamlet on a small asphalt road. In the past, it used to be a dirt road. The Camino de Santiago is not immutable. |

|

|

| Oaks are omnipresent, but sometimes also country and Montpellier maples, trees very common in all the Quercy causses. And then, a few withered brooms and thousands of dogwoods which now haunt the hedges. |

|

|

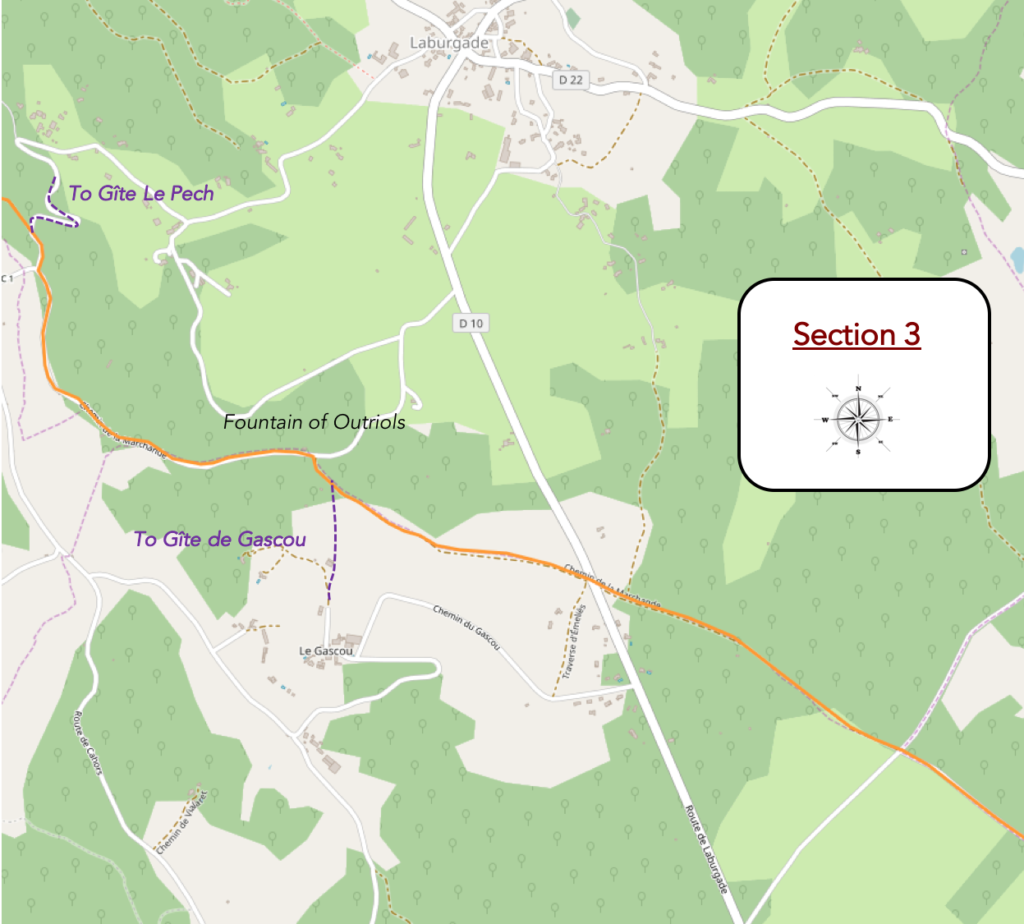

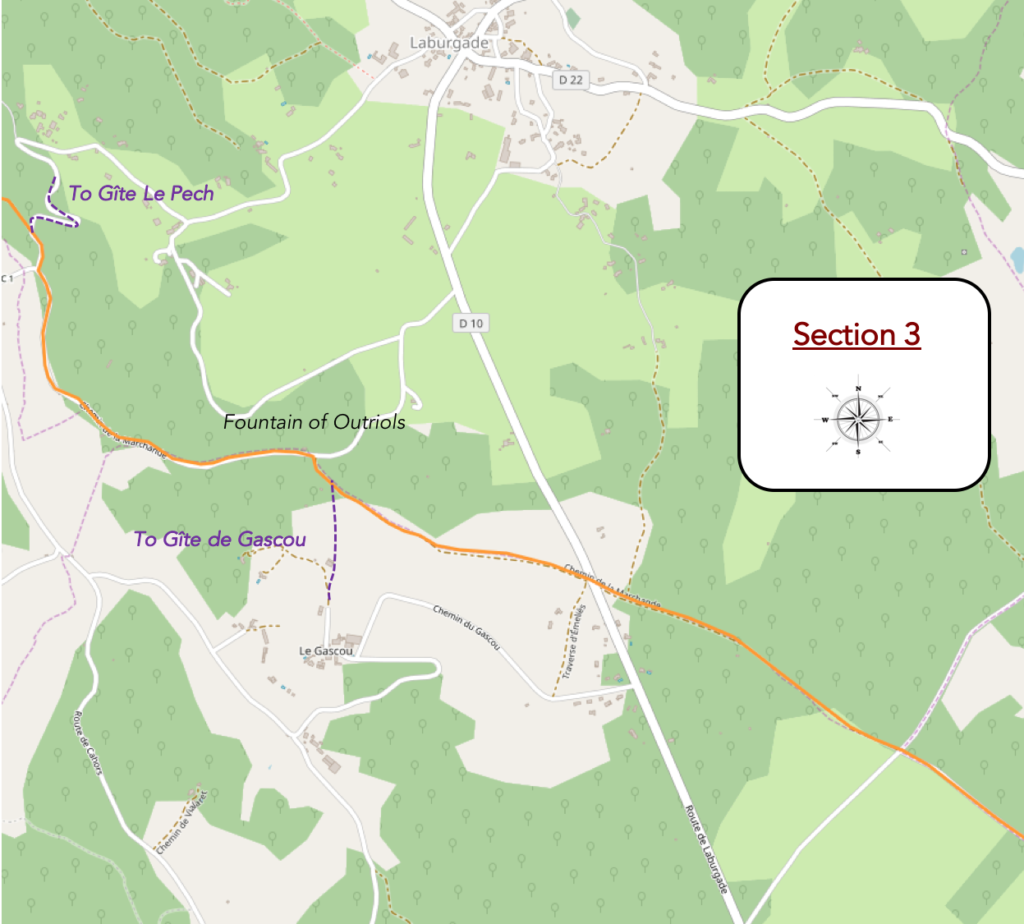

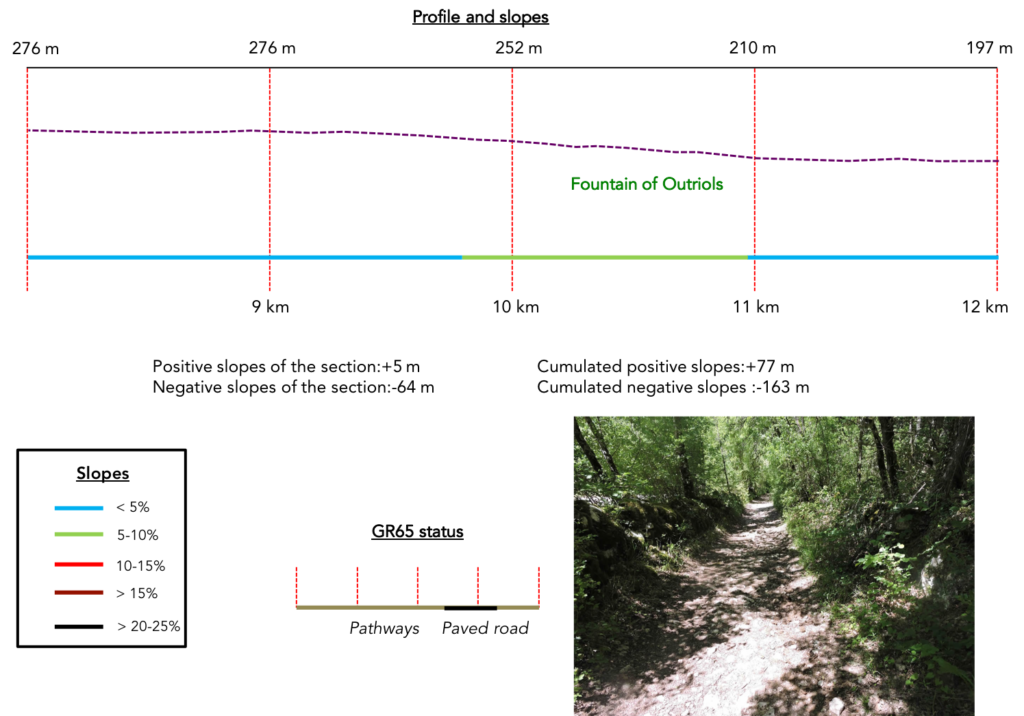

Section 3: Some undulations on the Cami Ferrat.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: course without any difficulty.

| Even though it is tarmac here, the route advances, peaceful, almost monotonous in its natural beauty. We can never say enough about the beauty of these low walls that line the route. Moss and lichen, in the causses, creep in everywhere, on the stones, on the trees, living or dead, weaving the space with thick curtains. |

|

|

| On the road, there is sometimes a small clearing. The gaze then falls on the rare truffle fields being plowed or on the steppe which stretches to the horizon. |

|

|

| Nothing moves, nothing changes along the oak trees. All you have to do is move forward and enjoy the silence. |

|

|

| A little further, the GR65 crosses the road which leads to Biargues. Sometimes, a rare vehicle travels on these remote roads in the hinterland. |

|

|

| Beyond the fork, the GR65 returns to the majesty of the dirt road. Here the clay is so smooth that you could play balls. |

|

|

| You are here a little over 16 km to Cahors. |

|

|

| The pathway finds back an environment, where the eye is lost in often sublime landscapes. |

|

|

| You are getting closer to an inhabited region. In this world of drought, sometimes an abandoned “caselle” emerges behind the oaks. |

|

|

| Shortly after, it is perhaps a working farm in the corner of the woods. |

|

|

| Further on, shelter, toilets, and above all water are announced. We understand, there is almost nothing to survive on the course. |

|

|

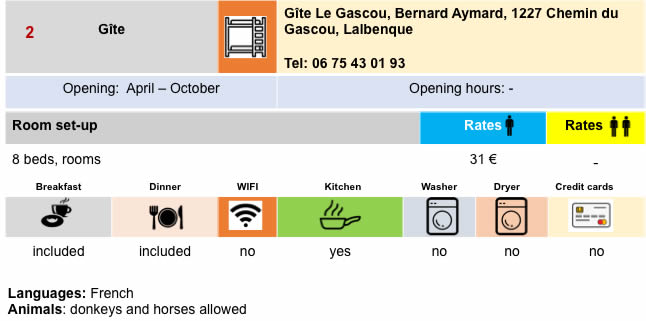

| The toilets are just a stone’s throw away, at the crossroads of the road leading to Lalbenque. This is the second shelter announced in Bach on the route. It is also just near here that the Gascou gîte was located, which is no longer reported. It had to change assignment. The particularity of today’s stage is to ignore the villages. Did Julius Caesar foresee this? Curious! Is it to preserve the attribution of the Bach-Cahors section to UNESCO heritage that the Cami Ferrat is hidden away from humans? |

|

|

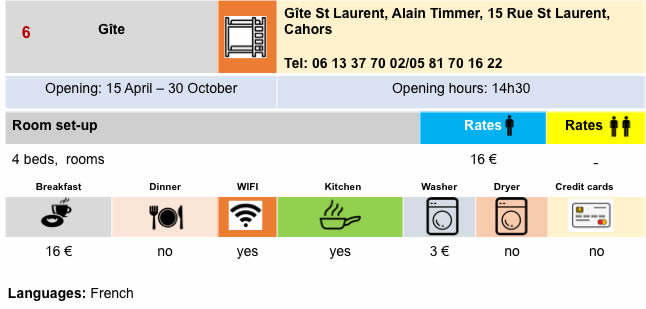

| On the other hand, the Le Pech gîte, further along the route, is still scheduled. |

|

|

A magnificent “gariotte” is hidden here under the trees.

| It is the return once again of a pathway, which undulates gracefully in the causse. You can hardly get tired of it. |

|

|

| Behind the walls, the country sometimes opens up. Only a few poor meadows allow rare farmers to survive by practicing a little livestock farming. Rarely will you find in the midst of the creeping aridity some vague cereals which hardly express themselves. |

|

|

| Suddenly the landscape changes, a bit as if we had changed countries. From being straight, the pathway becomes a little more tortuous in the undergrowth. It’s true that the pathway is changing. The stones clearly increase in number and size and there is even a bit of a slope. |

|

|

| At the bottom of the descent, the pathway finds an asphalt road in a small plain. |

|

|

At the side of the road is the Outriols fountain. The water here is not drinkable.

| You then have to abandon the dirt road to follow the asphalt road which heads towards the Le Pech/Laburgade junction. This is not the most exciting section of the day. But there is no reason to complain. You can’t always achieve excellence. |

|

|

| You arrive here 14 km to Cahors, shortly before the place called Le Moulin-Bas. |

|

|

| Further on, the road climbs slightly up a hill… |

|

|

| …to reach the Le Pech junction. The GR65 does not go to Le Pech. You have to make a detour of 800 meters to reach a gîte. |

|

|

| A dirt road then gently leaves towards the undergrowth. |

|

|

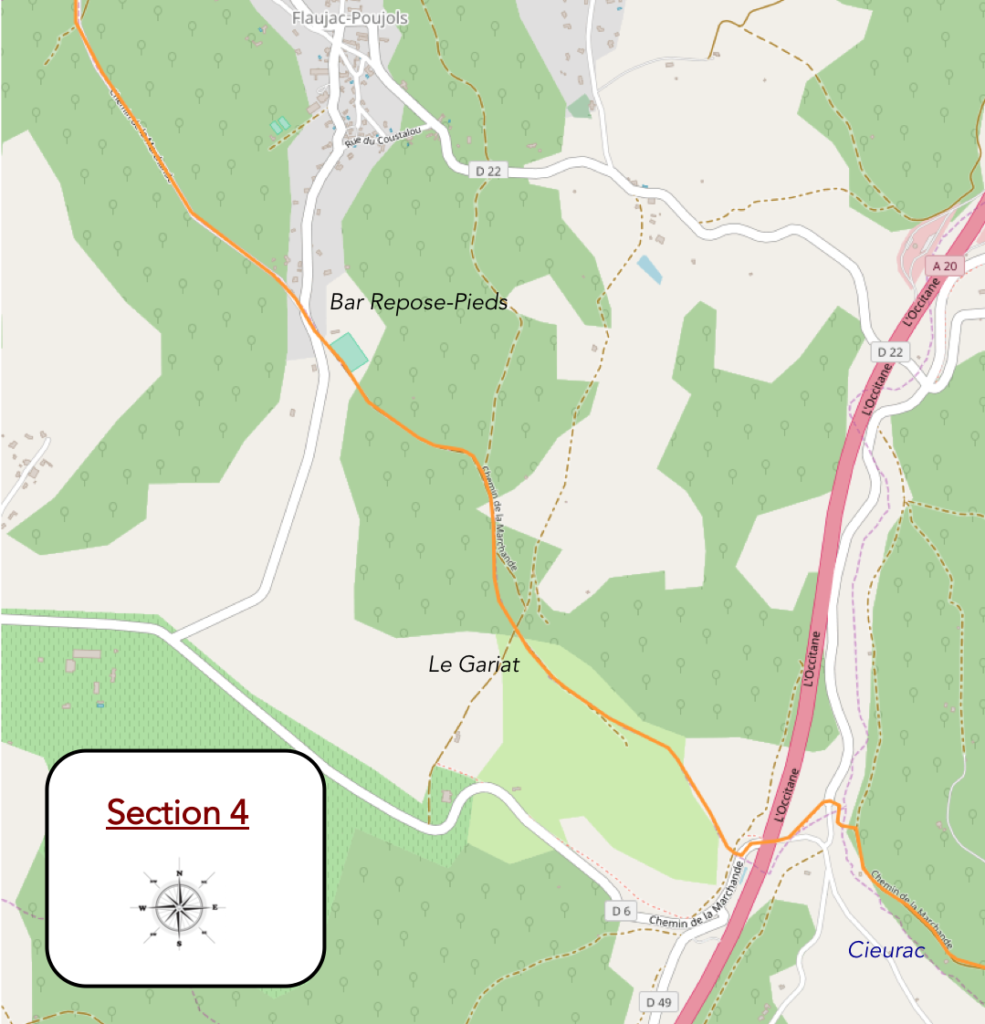

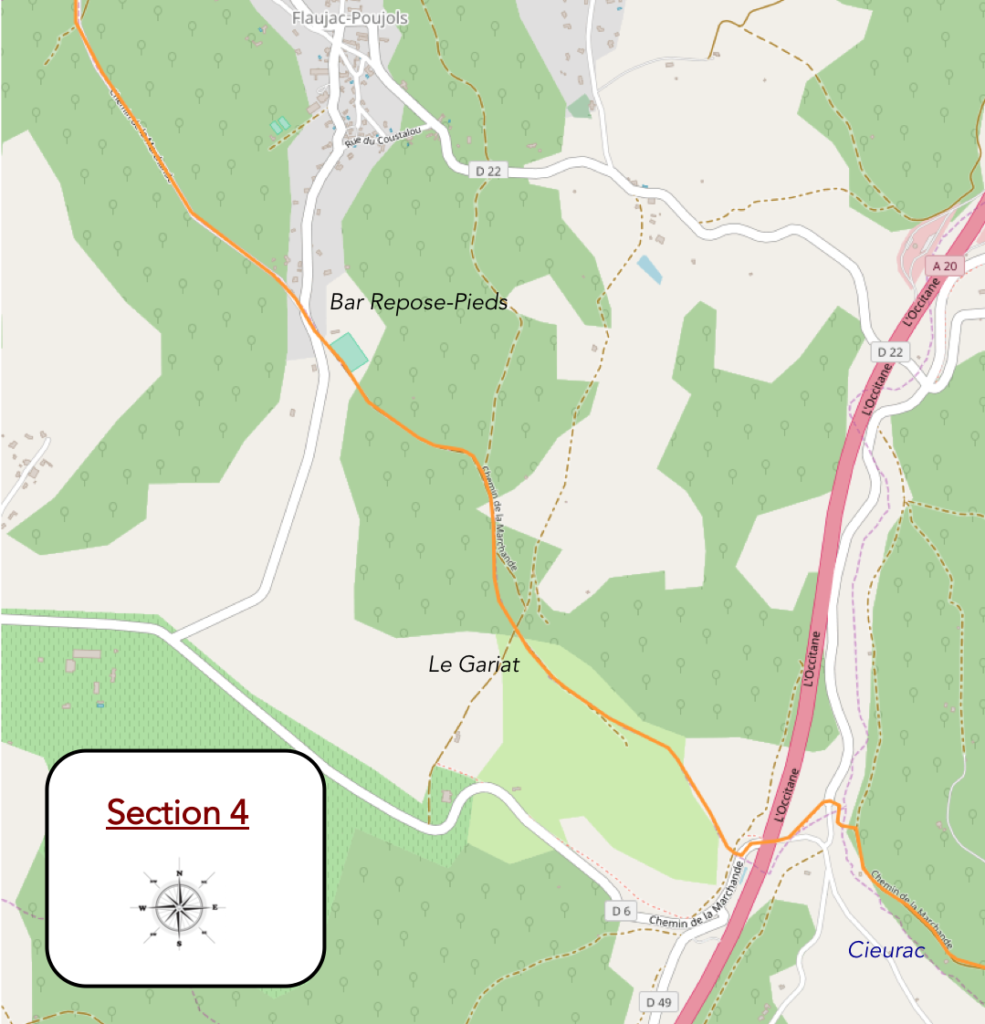

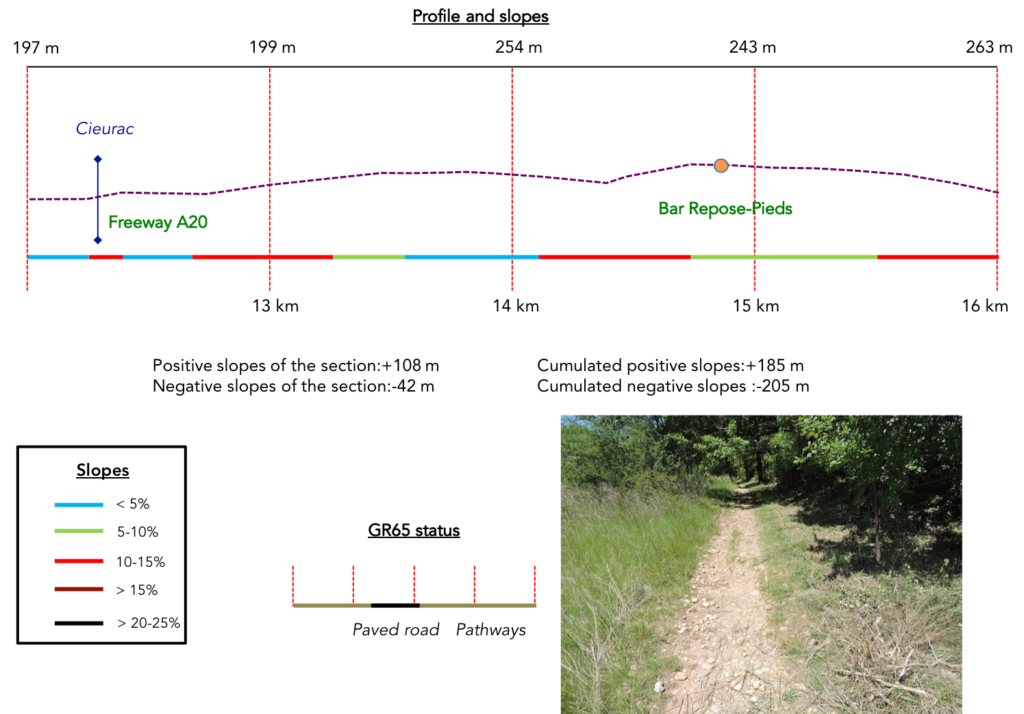

Section 4: The thrilling crossing of the highway before returning to the causse.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: some marked slopes, but nothing too severe.

| The pathway will follow the Cieurac stream. |

|

|

| It is a cradle of greenery where the small stream is lost, shy and almost invisible, under the foliage. We have never seen this stream in water. |

|

|

However, in the past, water had to flow here to operate the blades of the Moulin Bas.

| You can hear the engines humming in the distance, as the way approaches the highway. |

|

|

| Further on, the pathway crosses the Cieurac stream and finds itself in a sort of no man’s land, in front of a very complex road junction. The motorway bypass for vehicles is via the D6 road which passes above the motorway. |

|

|

| For the pilgrim, it’s simpler, he goes straight on a small narrow lane. |

|

|

| The small pathway does a bit of gymnastics in the weeds to end up under the motorway bridge. What a shock to suddenly find yourself in the heart of noisy civilization, after having been surrounded by silence for miles. This is the A20 motorway, known as L’Occitane. |

|

|

| Shortly after, the penitence continues in the form of a small embankment that must be climbed on the ocher dirt in the wild grass. |

|

|

| From up there, you have a panoramic view of the motorway and the D6 road which you will follow for almost a kilometer. |

|

|

The pathway goes back down from the hill towards the D6 road…

| …then it follows it into the rocks and into the steppe. |

|

|

| It is then a narrow, adorable pathway, which climbs quite steeply. |

|

|

| Further up, the pathway gets closer to the D6 road, eventually following it for a few hundred meters. |

|

|

| At a place called Le Gariat, the GR65 leaves the tarmac and returns to the undergrowth. Here you are 11 km to Cahors. On the Camino de Santiago, tar, dirt and stones go well together. They put up with it, because if the dirt roads belong to the pilgrim, the people here must be able to travel every day without facing potholes and the bumps of the tracks. |

|

|

| Tired of walking along the highway, its surrounding voids and its banal world, the pathway comes back to life and plunges once again into the undergrowth. Gradually, the car engines become silent in the woods. What silence! You can almost hear the trees rustling in the light wind. The GR65 starts again on stones and the pathway climbs to the top of the hill. |

|

|

| It then finds an asphalt road, which it will follow flat for a few hundred meters. |

|

|

| Further on, the GR65 finds back the full range of Causses tracks: stones on the track and oaks in huge numbers. What happiness! |

|

|

| The pathway wanders around here, passing near a reservoir. Is there really water here? |

|

|

| But the ride won’t last. You see that the slope increases. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope is almost 15% on large stones. However, the landscape remains the same, eternal and harsh at the same time. |

|

|

| The descent is quite long, throbbing to the bottom of a dale… |

|

|

| …but it is to slope back up immediately, with the same degree of slope and difficulty. |

|

|

| Some pilgrims are sweating profusely. Come on! This is the only major effort required on today’s stage. |

|

|

| Further up, the slope softens when the pathway heads to a beautiful ruin. |

|

|

| The pathway soon arrives near a football field. In the past, the Repose-Pieds refreshment bar was a welcome and essential stopover on the Camino de Santiago. It was often here that you saw pilgrims gathering for a well-deserved break. You would have done the same. The jovial keeper of the refreshment bar told you that he had rarely seen a pilgrim go straight in front of his shop. Today, everything seems to be over. Until when? All that remains is a water point and places for a picnic. |

|

|

| Beyond the refreshment bar, the GR65 flattens a little on the road. |

|

|

| But the plateau doesn’t last. A fairly long descent lies ahead. A “gariotte” winks at you under the trees. |

|

|

| Everything is still dry, despite some meager meadows which sometimes peek out over the hills. The pathway runs along what looks like a truffle patch growing on the crest of the hill for quite a long time. |

|

|

| Further down, the slope increases. Pebbles too. |

|

|

| At more than 10% slope, your feet are not sure on the rolling stones. All around, the oaks, so thin, will give you little shade. |

|

|

Section 5: Back to a little more civilization.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: slightly more pronounced undulations, but no slope is greater than 15%.

| And this little game on the stony pathway continues in the oaks and copses until the Pradelles junction, just before Flaujac-Poujols. Here again, you guessed it, the Cami Ferrat ignores the village |

|

|

You are here 8 km to Cahors.

| A first undulation is in front of you, but you can guess others, in a horizon that opens up a little. The route approaches Cahors, from dale to dale. Here a wide dirt avenue takes you towards La Quintarde and La Marchande, which are announced at the top of the hill. Another “gariotte” awaits you at the start of the track. |

|

|

| The pathway drags at the beginning a little next to a road where hardly anyone passes. |

|

|

| their minds wander. But for many walkers, the mind becomes accustomed to these quiet scenes where nature displays its know-how, beautiful or more common like here. The Roman diggers of the time only had to collect the stones around them to strengthen the track. There was no shortage of them, and probably never will be. And too bad, if the topography of the region was hilly. All they had to do was follow the false flats and the hills. Up, down, then up and down again, most often at the edge of the forest. Julius Caesar undoubtedly liked to see his troops transit, at the edge of the woods, so that he could take refuge there if necessary. |

|

|

| However, for many pilgrims, this kind of journey, uniform, without surprises, monotonous to the point of boredom, will not lift the soul. It’s still almost two kilometers to swallow, repetitive, from one bend in the pathway to the next. It’s no longer the magic of the causse. There is only one advantage. It doesn’t climb up much, but the end of the dale is always further away. |

|

|

| Further up, the situation is finally changing. The stones are back on the pathway, the slope too. It’s as if you found the causse back. |

|

|

| The pathway climbs a small bare hill… |

|

|

| …then it sinks into a little dense undergrowth. |

|

|

| Another small ramp and the pathway joins La Quintarde, which offers rooms and table. |

|

|

| Beyond La Quintarde, a road climbs to the top of the ridge. |

|

|

| Shortly after, a road takes you to Chemin de la Marchande. On the Camino de Santiago, as soon as there is an alternative to the road, you definitely go there. |

|

|

| Between Quintarde and Marchande, the route flattens along an area of small villas. The city is exported to the countryside, like everywhere. This is the only part of the road that changed Julius Caesar’s plans. |

|

|

| At the end of the pathway, it’s tarmac again, a crossroads. La Marchande is not a real village, rather a row of scattered villas. A sign announces the Chemin de Cabridelle. |

|

|

| At the exit of La Marchande, the GR65 follows the tarmac road for a few more moments, before returning to a typical Causses track. |

|

|

| Here the landscape changes drastically. The Chemin de Cabridelle, with dirt and stones, will get lost and undulate on small false flats, on a grandiose bare ridge, where the vegetation is rough, with its stunted oaks, its junipers, its wild grasses and its brush. |

|

|

| You’ll ask for more at every turn of the way, it’s so sumptuous. |

|

|

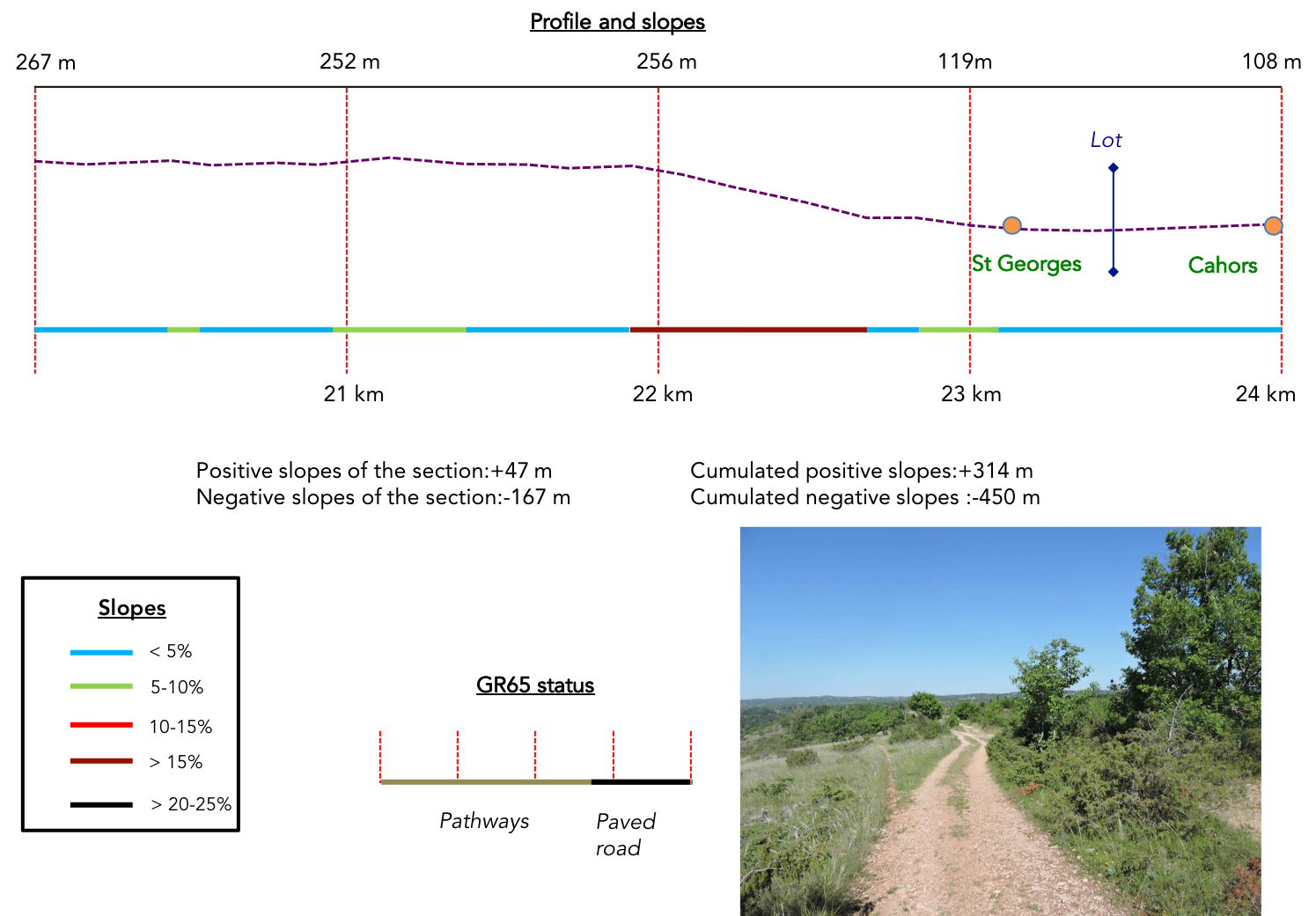

Section 6: All downhill, towards Cahors, jewel of the Lot.

General overview of the difficulties of the route: demanding descent, sometimes more than 25% slope towards Cahors.

| On the crest, the order of the place is great, whichever way you turn. It is the majestic Pech de Fourques which dominates Cahors. |

|

|

| Not a living soul. Nothing but the splendor of silence sometimes interrupted by crickets. The soul expands with the gaze. . |

|

|

| At the end of this long ridge that will fill you with happiness, the stony pathway ends on a small tarmac road, which flattens on the causse. |

|

|

| The road runs along the ridge for almost half a kilometer. |

|

|

| Further ahead, the horizon opens wide. The road begins to descend steeply towards Cahors, where you can see the railway bridge in the distance, and even further away the Valentré Bridge. |

|

|

| The descent is very demanding with a slope of more than 25% in places. |

|

|

Here is yet another ephemeral monument to the glory of the pilgrims.

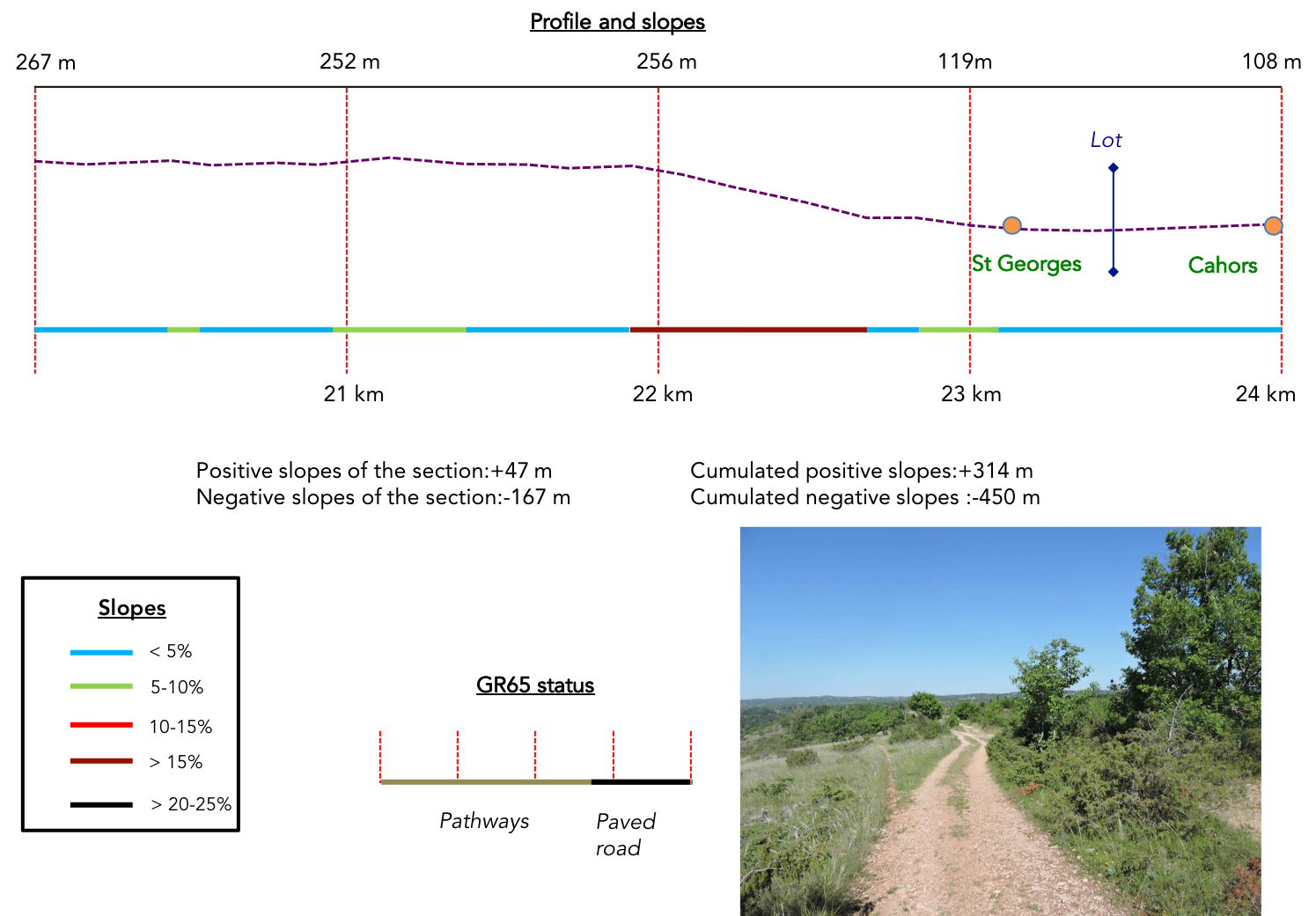

| The road arrives at the bottom of the descent at Chemin du Pech de Fourques, near the railway line, in the St Georges district, a suburb of Cahors. |

|

|

| The pilgrim then reaches the Louis Philippe Bridge. The Lot River is at his feet, calm, peaceful. |

|

|

| At the end of the bridge, it is in Cahors, in the city center. |

|

|

Section 7: In Cahors.

| Cahors is the only medium-sized town along the Camino de Santiago in France. The city itself contains 22,000 inhabitants, but the greater Cahors almost 50,000. The city, enclosed in a loop of the Lot, is cut in two by Boulevard Gambetta, the main axis which crosses the city, with its gigantic square and its shops. It is on this boulevard that Cahors is teeming with activity and people. |

|

|

Léon Gambetta (1838-1882), a great French politician during the Third Republic, was born in Cahors. The city entrusted the sculptor Alexandre Falguières to erect a monument to his glory, immediately after the death of the great man. The statue of Gambetta sits on a gigantic square above a fountain.

| The old town is wedged between the boulevard and the Lot, on one side of the Lot loop. The other half is more modern, less interesting. Old Cahors is made up of narrow streets and small shopping streets. |

|

|

| In terms of monuments, in the old town, Saint-Étienne Cathedral, built between the 11th and 12th centuries, is listed as a UNESCO world heritage site, as part of the Camino de Santiago in France |

|

|

| It is remarkable for its domes. It houses the Headdress of Christ, brought from the Holy Land. But it is not the only church in the world to have the divine head covering! The interior is so dark that it is impossible to photograph it with a conventional camera. Here we borrow one of the two images from Wikipedia Creative Commons; author PMRMaeyaert. |

|

|

In the adjoining cloister, in flamboyant Gothic style, sculptures represent pilgrims, drunkards and musicians.

Jacques Duèze (1244-1334), born in Cahors, became pope in Avignon in 1316, under the name John XXII. It was the latter’s brother who rebuilt his father’s house to turn it into a palace. The latter was demolished for the repair of the Pont Neuf. What remains is a magnificent tower, five stories high.

| Cahors is above all the majestic Pont Valentré, also called the Devil’s Bridge, or Balandras Bridge, in Occitan. It is obviously part of the UNESCO world heritage. Recently, vines were added to it, to clearly mark its belonging to the wine-growing heritage of the region, although there are no vines, or almost no vines, in Cahors. |

|

|

The bridge is a speed bump more than 100 meters long, with 6 large pointed arches, in Gothic style. It is flanked by three square towers with battlements and machicolations which dominate the Lot, at a height of 40 meters. A legend runs in Cahors about the construction of the bridge. As the work progressed little, the project manager signed a pact with the devil, pledging his soul. And of course, the bridge rose quickly. To save his soul, the head of the works asked the devil to provide himself with a sieve to draw water from the Carthusian spring. As clever as he was, the Devil failed in his enterprise. To take revenge, he came every night to unseal the last stone of the central tower. And the game lasted for centuries…/In 1879, during the restoration of the bridge, the architect had a stone sculpted with the effigy of the demon placed in the empty space. And since then, the demon has remained desperately clinging to the ridge of the bridge.

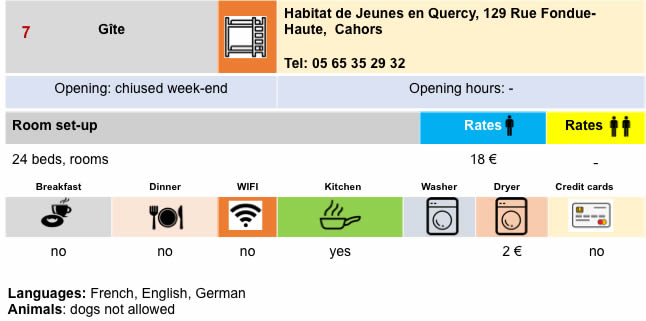

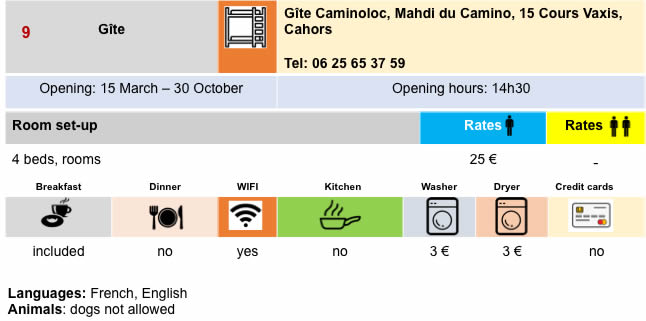

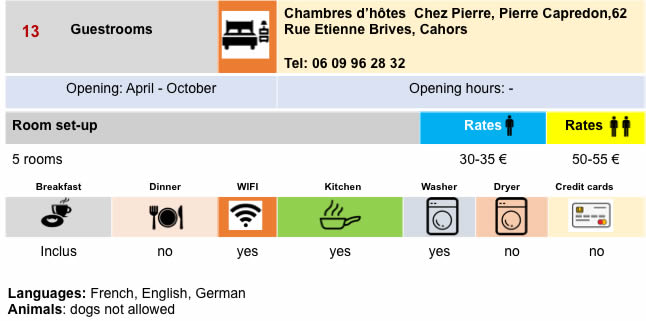

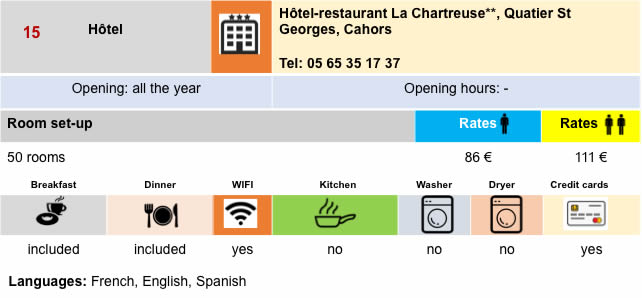

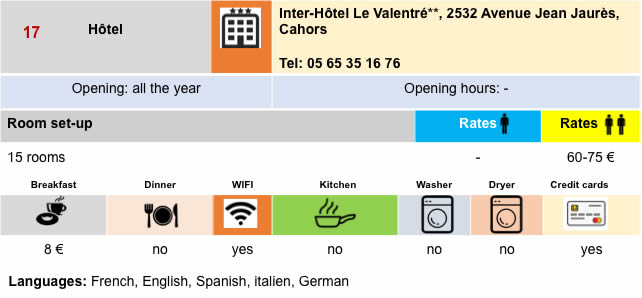

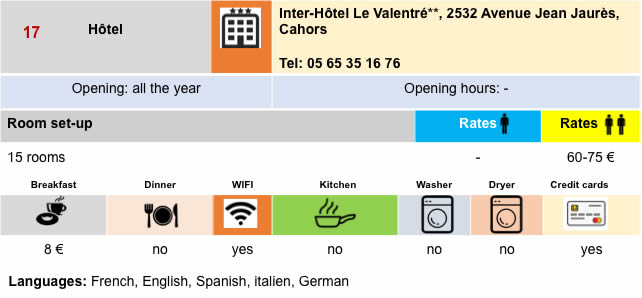

Lodging

Feel free to add comments. This is often how you move up the Google hierarchy, and how more pilgrims will have access to the site.

Here we move to anoter site from Cahors to St Jean-Pied-de-Port..-

|

|

Next stage : Stage 17: From Cahors to Lascabannes |

|

|

Back to menu |

The Cami Ferrat is above all about wide dirt roads. Little tar, the dream, right?:

The Cami Ferrat is above all about wide dirt roads. Little tar, the dream, right?: